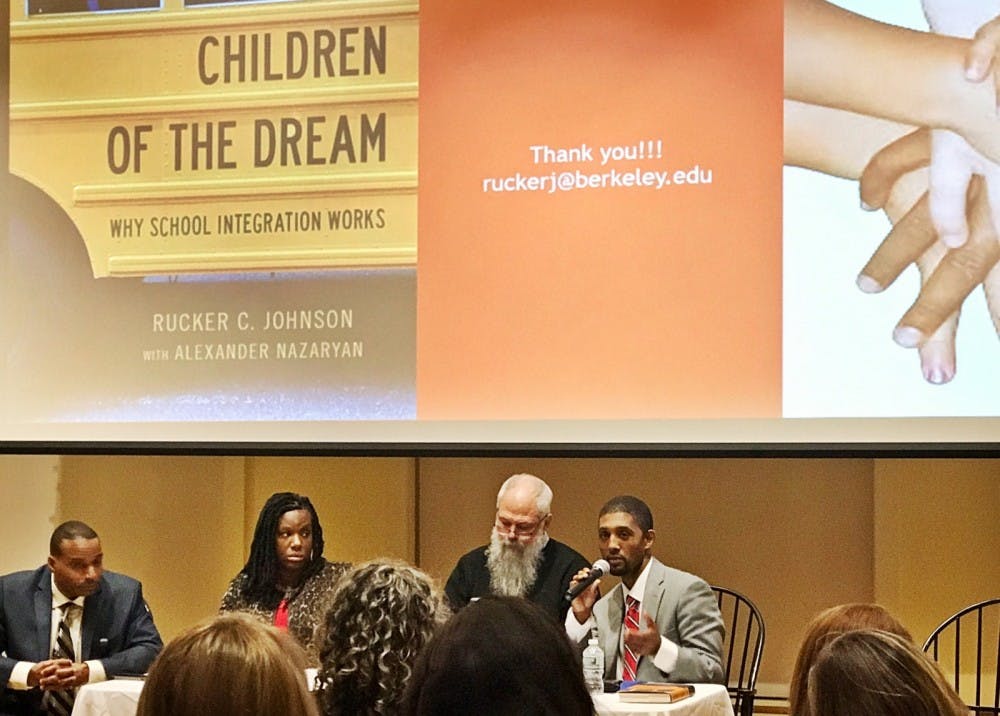

Rucker Johnson, the Chancellor’s Professor of Public Policy at UC Berkeley, discussed his new book Children of the Dream: Why School Integration Works on Friday. Brandon Scott, Baltimore City Council president; Cristina Evans, chair of the Teacher Chapter of the Baltimore Teachers Union Executive Board; and Eric Rice, assistant clinical professor at the School of Education, served as respondents. The 21st Century Cities Initiative (21CC), an on-campus center focused on using big data to solve modern urban challenges, organized the event.

Johnson set the stage for the night’s discussions about the benefits of school integration by first emphasizing that the three largest equal-education opportunities currently being pursued in the nation are school integration, school funding reforms and timing of pre-kindergarten investments. Before jumping into the data he wrote about in his book, he clarified that desegregation is only the first step of integration.

“Moving from desegregation to integration is moving from access to inclusion, it’s moving from exposure to understanding, and that is a process that doesn’t happen overnight,” he said.

Johnson detailed the effects for both white and black students of court-ordered school desegregation on the change in the years of completed education, changes in adult wages, the annual incidents of poverty in adulthood and the chances of being incarcerated.

Johnson highlighted that — contrary to popular concerns that school integration was a zero-sum game in which resources were taken from white students to give to black students — there is no evidence that white students were negatively impacted by integration.

He showed that school integration not only led to rapid increases in educational attainment for black students, but that this greater education attainment translated into significant increase in wages earned in adulthood and decreased poverty and likelihood of incarceration. Together, all of these factors served as crucial catalysts for forming a black middle class, Johnson argued.

“Integration led to the severing of the intergenerational cycle of poverty,” Johnson said.

However, after establishing that integration does indeed work, Johnson went on to address the continued existence of significant black-white student achievement gaps in integrated schools across the country.

This is particularly the case in Baltimore City, Johnson said, where black children’s achievement scores are consistently two grade levels below their white peers.

“There’s not a single district in the country that’s even moderately segregated that doesn’t have a significant black-white achievement gap,” he said.

Johnson argued that since integration itself is not enough to reduce these achievement gaps, state and federal governments must also address inequities in school funding, housing and health care.

Rice wanted to know what Johnson would do to address school integration given its long-contested history.

“One of the missing ingredients in all of these conversations about integration is who is at the head of the classroom and how are we supporting those teachers that are doing the real heavy lifting,” Johnson said.

Johnson emphasized that the current teacher salary structure is ironically designed to distribute lower salaries to teachers working in more disadvantaged areas, thus causing many talented teachers to leave urban areas, such as Baltimore City, for more affluent areas.

“In 33 states across the country, black and Hispanic children are two times more likely to be taught by inexperienced teachers [than white children],” he said.

Johnson stressed that maintaining a diverse and high-quality teaching workforce is vital to successful school integration and reducing the black-white achievement gaps.

For Scott, Johnson’s presentation brought up old memories from his father’s educational experience as well as his own.

He explained that his dad had been in middle school when the court-ordered desegregation was implemented, yet he always tells Scott that he believes he had a better education before school integration, simply because his new teachers did not seem to value the black students as much as the white students and they were constantly being placed into situations that disrupted their learning.

Scott recounted a day during his father’s junior year of high school when a white classmate that lived directly across from their high school came to school with a gun. The student’s father, who instructed him to shoot one of his black classmates, had given him the gun. Luckily, the gun was confiscated before it could be used.

“Think about the hatred that his dad had to have to try to force his son to do this,” Scott said.

Scott went on to address his own positive experience with school integration in Baltimore. He grew up in Park Heights along with four other friends but attended the city-wide advanced academic program at Roland Park Middle School in 1995 with only one of those friends.

Both he and his friend that attended Roland Park currently have successful careers working for the City. But of their three other friends that remained in Park Heights, two have passed away and one is struggling with substance abuse issues.

“When you look at him and I compared to them, there’s not much difference — we lived in the same neighborhood, saw the same violence. The difference was that we went to Roland Park Middle [School],” Scott said. “[Integration] works, we just have to be willing to cut through the racism.”

At the end of the panel, an audience member asked Johnson whether any of his research has focused on quantifying either the harm that black students may have experienced by being exposed to majority-white educational environment, or the benefit that they may have experienced by being exposed to majority-black educational environments.

Johnson acknowledged that there is and remains a certain amount of bias that some teachers have against minority students in which they fail to recognize their capacity for achievement, thus creating negative school climates.

“I believe that integration is like surgery on a school system — it leaves scars, but it heals,” Johnson said. “The diversity of our school children is here to stay; the question is if we are going to harness that… or are we going to continue to shun it.”

For Myles Handy, deputy press secretary and legislative liaison for Mayor Bernard “Jack” Young, Johnson’s discussion and the panelists’ viewpoints were thought-provoking.

“It brought me back to my experiences growing up. I went from a primarily African American school to a majority-white institution and [the talk] really made me reminisce on that transition,” he said.

Correction: A previous title of this article misidentified the name of the 21st Century Cities Initiative.

The News-Letter regrets this error.