Two and a half years ago, Nathan Connolly, a professor in the History Department, submitted a motion calling on Hopkins administrators to rename the Woodrow Wilson Fellowship in light of the former U.S. president’s racist legacy. Connolly — along with the Homewood Faculty Assembly, which voted to support his motion — is still waiting for an answer.

“We put a referendum on the table in November 2016 to be voted by the Homewood Faculty Assembly about renaming the Woodrow Wilson Fellowship and establishing a committee to come up with a more suitable name,” he said. “We recognized that Wilson was no longer the namesake that we wanted applied to our most illustrious undergraduates, who were going on and doing research.”

In recent years, several schools have struggled to contextualize and come to terms with their racist pasts. Many colleges and universities uncovered racist images of blackface and lynching in their yearbooks, and the question of whether to remove Confederate monuments or rename buildings remains contentious. In March, Woodrow Wilson High School in Washington, D.C. announced that it would consider changing its name.

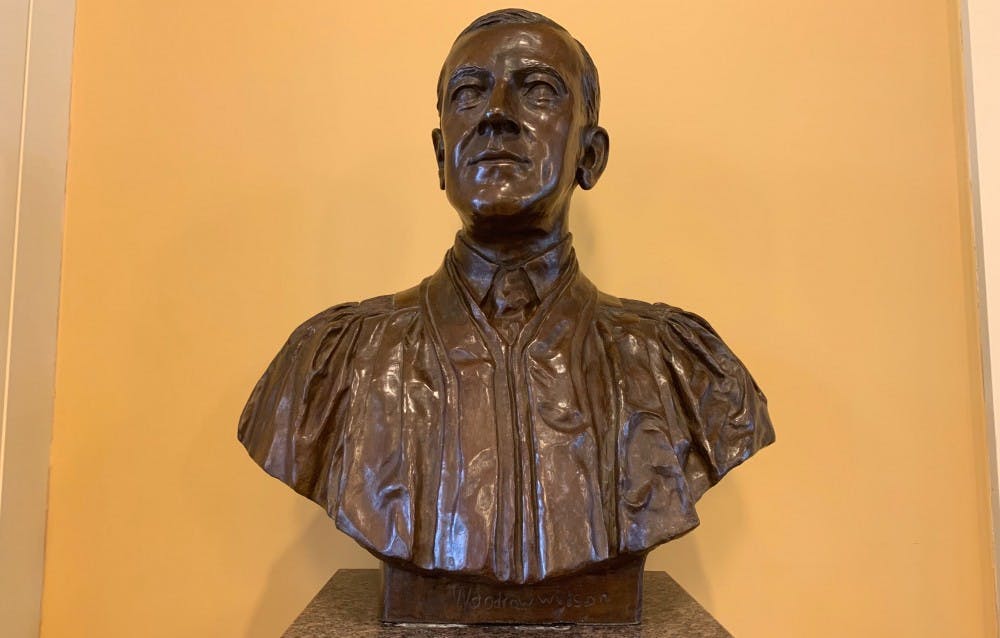

At Hopkins, Wilson’s name is most visible on the Woodrow Wilson Fellowship, a prestigious $10,000 research award granted to incoming and current freshmen. A house in the dorm Alumni Memorial Residence I (AMR I) is also named after Wilson, and there is a bust of Wilson in Mason Hall, where the Office of Undergraduate Admissions is located.

Wilson received his PhD in political science from Hopkins in 1886. His critics point to his racist views and policies: He defended the Ku Klux Klan, opposed the admission of black students to Princeton University and segregated the federal workforce.

Others, however, highlight Wilson’s achievements not only as the 28th President of the U.S., but also as governor of New Jersey and president of Princeton. He created the Federal Reserve System, guided America during World War I and won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1919.

Princeton’s board of trustees recruited Connolly, along with eight other historians, to help assess Wilson’s legacy following a series of protests in Nov. 2015. After student activists staged a 32-hour sit-in demanding that the school strip Wilson’s name from university buildings, Princeton’s board of trustees agreed to consider the protesters demands.

Princeton’s board of trustees voted to retain Wilson’s name in 2016. In their report they wrote that, “the University needs to be honest and forthcoming about its history,” and outlined initiatives to make Princeton a more diverse and inclusive space.

In an email to The News-Letter, University President Ronald J. Daniels explained that any requests to rename the Wilson Fellowship at Hopkins would need to be fielded by Dean Beverly Wendland of the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences (KSAS) and Provost Sunil Kumar.

“Renaming a prominent program or other feature of the university is a serious matter and cannot be done lightly,” Daniels wrote. “Any decision to rename the Wilson Fellowship must be guided by principles that can be consistently applied to all renaming requests. We will consider standing up such a process this coming fall.”

Three prominent Hopkins affiliates were involved in establishing Wilson Fellowship in 1999, including former Krieger dean Herbert Kessler, Class of 1979 Alumnus Barclay Knapp and Political Science Professor Steven David. David, the former program director of the Wilson Fellowship, explained why Wilson’s name was selected.

“He is the only president to have received a degree from Johns Hopkins University,” David said. “Moreover, in international relations, Woodrow Wilson is a giant in the field. He is the father of liberal internationalism: The notion that the spread of democracy throughout the world is a good thing. He championed the course of self-determination.”

Though David said he would be disappointed if the fellowship were to be renamed, he also acknowledged the value in creating a committee — composed of students, faculty and Wilson fellows — to critically examine Wilson’s legacy. David added that he would understand if the community decided that the fellowship should be renamed.

For Corey Payne, a Ph.D. student in the Sociology department, renaming the fellowship is an easy decision. A graduate of the class of 2017, Payne received the Wilson Fellowship as an undergraduate and in 2016, he, along with 37 other fellows, wrote a letter in support of the Homewood Faculty Assembly’s motion.

“Our University’s continued prominent association with Woodrow Wilson marks Johns Hopkins University as an intellectual birthplace of modern racism at home and abroad. These ideals stand counter not only to our values as an academic institution, but also to the values espoused within the Wilson Fellowship,” the letter read.

Payne was disappointed that Hopkins officials failed to offer a response to the Homewood Faculty Assembly’s motion in 2016. In addition to the original motion, Connolly sent a follow-up email to Hopkins administrators in August 2017, shortly after Baltimore took down its four Confederate monuments. He did not receive a response.

“This is just one example of President Daniels and his administration really ignoring the democratic will of the faculty and students who make up this University,” Connolly said. “This administration’s unwillingness to deal with the racist histories of our institution and the people who made up our institution are being reproduced in these new programs that they’re embracing, like the private police force.”

Failing to reconcile with an institution’s racist past, Connolly said, has a significant impact on the current climate at Hopkins. Connolly could not recall any buildings on campus named after people of color, and expressed concerned over the University’s commitment to recruiting a diverse student body if it continues to celebrate its racist figures.

“There is absolutely a competing interest between the inability of an institution to reckon with its history, and its efforts to reach out to a global community and engage with diverse recruiting,” he said.

In Payne’s experience, the Wilson Fellowship community was inclusive, though he noted that it struggled with recruiting students from diverse backgrounds when he was an undergraduate.

Natalie Strobach, the director of undergraduate research and current Wilson Fellowship program director, stated that ensuring that the Wilson Fellowship is inclusive goes beyond looking at its name.

Strobach explained that she has worked to reduce barriers so that more students from underrepresented racial or ethnic backgrounds apply and receive the Wilson Fellowship. For example, she helped to change the application scoring system to weigh creativity, need for research and project feasibility over past experience.

“We need to think more broadly — beyond if a program’s name may be alienating — about how the research projects themselves need to also be as ethically informed as possible, mindful of the diverse communities we’re researching in, accountable within human subjects research, and accountable to a range of scholarly voices, whether they are from diverse religious backgrounds, racial or ethnic, or socioeconomic,” Strobach wrote.

Current Wilson fellows, like senior Rachel Underweiser, have conflicting views on whether to rename the fellowship. For her research, Underweiser studied anti-Semitism on college campuses in the U.S. and United Kingdom. Given her work as a Wilson fellow, Underweiser said that it is important for students to be aware of racism in the past and present but that she does not feel it is necessary to remove Wilson’s name from the fellowship.

“Wilson was a problematic figure, but he also did a lot for our country that was very great,” she said. “We can’t look at him as though he’s from our time. He was a completely different time and different world.”

Other Wilson fellows like junior Alan Fang, however, believe that the program should be renamed.

“Ultimately, it should be changed,” he said. “In the long run, it will be viewed as a positive, more progressive step toward reconciling with America’s history and a step toward being more socially responsible.”

However, Fang noted that the discussions surrounding removing Wilson’s name differ from the national conversation over whether to take down Confederate monuments, or remove the names of Confederate generals from buildings. Fang said that while present-day white supremacists glorify the Confederacy, they rarely point to Wilson as a symbol or icon for their movement.

“No one is rallying around Woodrow Wilson to promote white supremacy or racism,” he said. “People barely know what Woodrow Wilson did.”

Kevin Kruse, a professor of history at Princeton who studies race, segregation and the civil rights movement, explained that Wilson was considered racist even by early 20th century standards.

“The idea that there was no one at the time speaking out against white supremacy or in favor of civil rights is deeply ahistorical,” he said. “There clearly were people at the time who objected to Wilson’s stance on race.”

Kruse expressed appreciation for the way that Princeton has worked to more accurately represent Wilson as a historical figure.

In March, Princeton officials announced plans to install an exhibit that reflects both the positive and negative aspects of Wilson’s legacy. The installation, called “Double Consciousness,” will feature unedited quotes to represent Wilson’s views on different issues. Kruse said that representing the past with nuance is key to creating an accurate portrait of history.

“You don’t want to simply erase these people from the past because, for better or worse, they shaped the institution,” Kruse said. “You need to grapple with that and not simply accept the myth that was presented about them.”

Connolly emphasized that Hopkins administrators should take into account that Wilson’s racist legacy began while he was a student at the University. Wilson studied with Thomas Dixon Jr., a Confederate sympathizer. Dixon’s published works were the basis for D.W. Griffith film The Birth of a Nation, which characterizes the KKK and Confederacy in a positive light.

Connolly noted that long before Wilson screened The Birth of a Nation in the White House, he supported the ideas espoused in the film as a graduate student.

Wilson and Dixon also took classes taught by Herbert Baxter Adams, the namesake of the chair that Connolly occupies. Connolly pointed out that it is ironic for him, as a black faculty member, to hold a professorship named for a man whose scholarship supported racist viewpoints.

“I occupy that chair with no lack of appreciation for the irony — given the kind of work that I do in anti-racist ways — in wanting it to never be forgotten that I’m trying to help reshape the legacy of Hopkins,” Connolly said.