Claire Denis’ film High Life, which was released on Friday, April 12, is definitely unique. And it is also certainly a showcase of the most bodily fluids I’ve seen in a science fiction film, so much to the point where I pledged to walk out at five different points. But the film has an impressive and elusive gravity to it that kept me in my seat, despite being grossed out right up to my limits.

It starts out charmingly enough. Robert Pattinson’s character floats in space, repairing the outside of a ship. He listens to his baby daughter babble through a baby monitor. In an unsettling image, the child sits in a playpen in a darkened room that blinks with futuristic machinery. I immediately felt that classic sense of claustrophobia that comes with space movies. We are then introduced to the different beige chambers of the ship, where we see the garden, a room filled with lush greenery, misted with water. The visuals are pretty and the colors are muted and hazy, calling back the aesthetics of seventies art-house science fiction films like Stanley Kubrick’s A Space Odyssey or Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris.

But unlike these films, it doesn’t feel like it’s actually in space. This is probably thanks to (or no thanks to) the sparseness of the set and the lack of technology and equipment that surely would’ve made up a real spaceship; instead, there are uncomplicated space suits, a few computers and several analog-looking contraptions.

Everything about the technicalities of a spaceship and the circumstances of floating in a different solar system feels oversimplified or glossed over. The movie leans instead on its premise, asking us to suspend disbelief and believe the backstory that’s told through Robert Pattinson’s voice-overs as the exposition unfolds.

But as an audience, we’re left with a series of questions. Where is this ship? What happened to Earth? Why is there a baby? What is the ship’s mission?

These questions arise in just the first minutes of the film, and from there onwards, the plot struggles to clear up or explain these logical problems. But logic becomes almost besides the point as the movie changes from its innocent and quiet beginning to something much, much weirder, pushing the limits of its R-rating. It’s unexpected, for better or for worse.

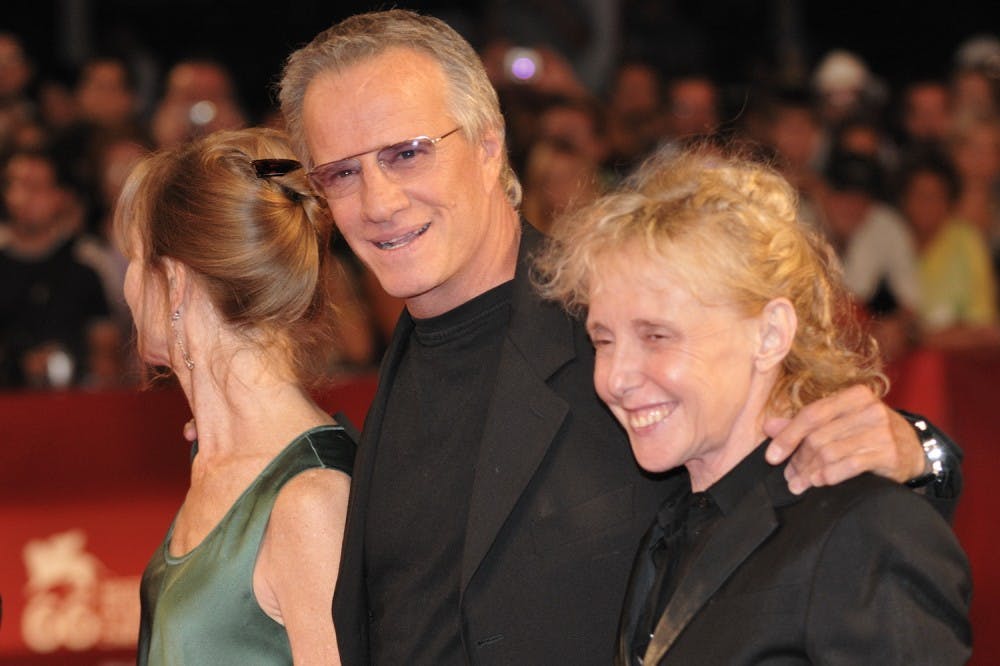

The film is made by famed French director Claire Denis, whose movies I hadn’t seen before High Life. Honestly, I had never previously heard of the films that made her into a revered filmmaker. Her films touch on post-colonial themes by drawing on her childhood spent in various African nations. The films are often classified as “art house,” a term that could possibly describe High Life, too.

“Art house” is a term that I personally understand to mean a movie that tries to be more artistic than entertaining. High Life certainly tries for this kind of artistry and poetic cinema. The shots are long, lingering and carefully framed. All the colors are curated into a complementary, washed-out, earthy palette. The scenes between the action, which take up nearly as much time as the scenes with action, rest patiently on the subjects and their environments.

It’s often quite mesmerizing, but it’s slow. It’s hard to tell what’s happening, though the images feel grounded and realistic. If that’s your style, then you’ll probably like this movie.

As the subject matter becomes more experimental, there is, most unforgettably, a scene in which the spaceship’s crazed scientist enters what’s known as “The Fuckbox” and violently masturbates in a dizzying five-minute sequence of blurred visuals and manic energy.

From this point, sex and semen come onto the screen nearly every other scene. This explicit voyeurism is arguably difficult to participate in, and the scenes are relentless and progressively squirm-inducing. It’s bloody. It’s a dog-eat-dog world. It’s almost numbing.

The performances were also difficult to like at times. Mia Goth’s character, one of the inmates on the ship, goes through awful and heart-wrenching events, yet remains difficult to connect with.

Maybe this is because it’s hard to lose yourself in a story where we’re expected to believe the ship is for death-row inmates, while the cast is full of French beauties, art-world influencers and André 3000. Pattinson’s performance, though, is a little more magnetic.

He keeps you watching, communicating the strength and stoic parental love of his character in a convincing way.

At one point his character holds his baby, telling her through gritted teeth about having to eat your own “piss and shit.”

“Ta-boo...ta-boo,” he says.

He repeats this to her, emphasizing the lullaby-like quality of the two syllables of the word “taboo.”

This film is definitely just that, and according to this line, it seems to be self-aware of this fact as well.

“Taboo” is everywhere, so be prepared to be faced directly with it. But the taboo arises out of horrible moral circumstances and points to important ethical implications of things like the treatment of incarcerated people, about scientific and medical experiments and the complexities of parental love. It’s a movie that pushes its audience away, knowing that it’s too difficult to face these implications directly. But it’s worth seeing, thinking about and deciding for yourself if it’s worth the effort.