I’d never heard of the film Wild Strawberries before The Charles Theatre put it as the most recent choice for their weekly Revival Series — a Swedish film from 1957 about a grumbling old man isn’t something I’d bet money on enjoying. But as with most Revival Series selections, I left the theater with a feeling of gratitude, an opinionated argument for going to random screenings and texting everyone in my contact list to “immediately go watch the most underrated movie of all time.”

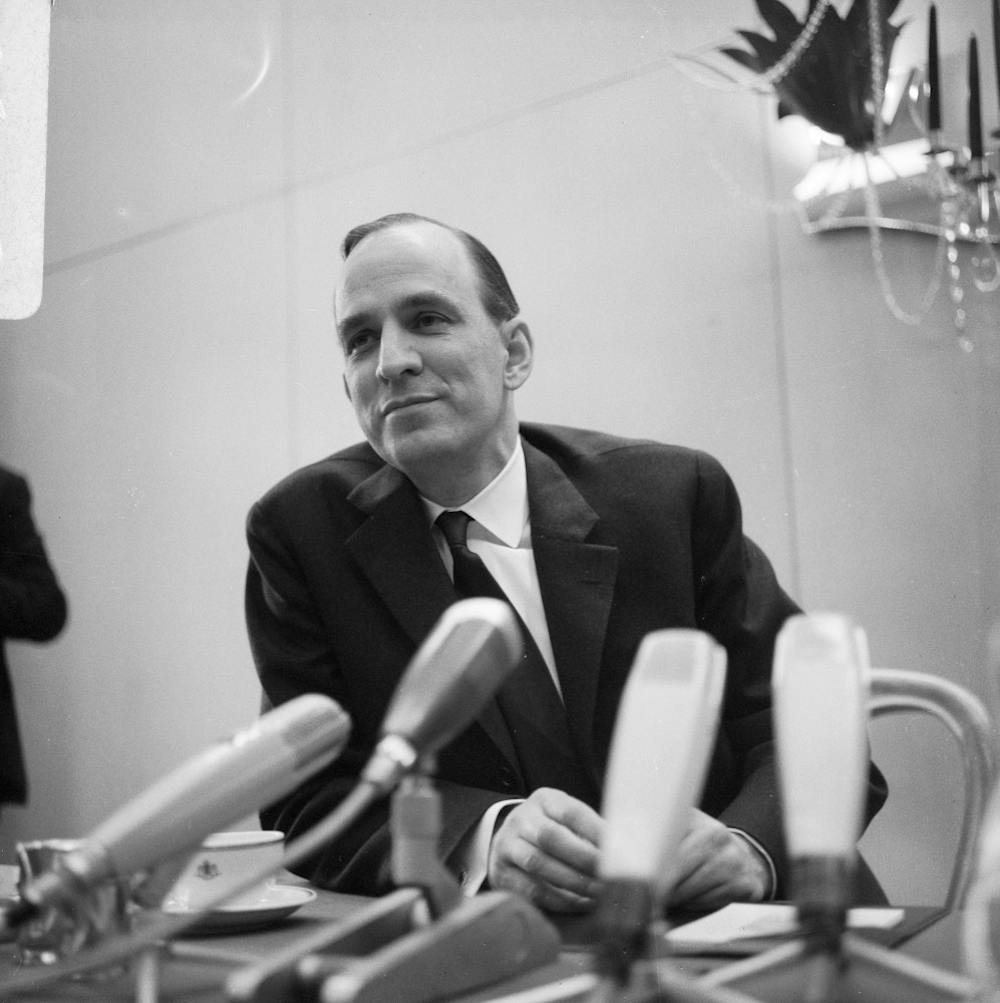

I saw the film on Monday, March 9, one of its three showings, and I walked into the theater ignorant of its artistic significance and status in the film world. The film’s director, Ernst Ingmar Bergman from Sweden, directed over 60 films and 170 plays in his lifetime, both in Sweden and around the world. He became known in the ‘50s and ‘60s for his existential modernist works on both the screen and the stage, and his impact was immediate.

A classic Bergman film is considered a directly heavy one, wrought with philosophical themes and steeped in depressing questions like, “What makes a life worthwhile?” In his film Shame, a war ravages around a married couple who struggle to survive in its endless midst. In From the Life of the Marionettes, a murderer spirals into psychological anguish after his brutal killing of a prostitute. But Wild Strawberries, considered to be an accessible entry point to Bergman’s cinema, isn’t weighed down by cynicism. Despite the film dealing with an end-of-life crisis, I found it to be a sincere argument for the warmth at the core of ourselves and humanity.

Bergman used his works to investigate his own demons, and Wild Strawberries uses the aging Dr. Isak Borg (same initials as Ingmar Bergman, wink wink) to explore the journey of confronting the flawed self. In the first moments of the film, Borg barks condescendingly at his longtime housekeeper as he decides to drive alone to receive an honorary degree. But when his daughter-in-law Marianne asks him for a last-minute lift back home after getting into an argument with her husband, the two set out on a car ride across Sweden where Marianne frankly admits she detests Borg, which starts him off on a series of reflections on his life.

The car becomes a literal trip down memory lane, places and people sparking dream-sequences. Marianne and Borg pick up hitchhikers including the charming, feisty, blond-headed Sara, a girl who shares the name of Borg’s former love. Sara also bears an identical resemblance to the girl from Borg’s past — the two Sara’s are played by the same actress (though this is hard to recognize through the costuming). Two young men accompany Sara, their serious and carefree personalities conflicting, and their bickering reminds Borg of his younger self. After the young people, Borg and Marianne pick up a fighting married couple and then visit Borg’s ancient and detached mother. The film explores all kinds of people throughout generations, from innocent young-adulthood to the disillusioned precipice of death. Each scene exposes the vulnerability of the people around him, then in himself as he is forced to reckon with the swelling emotions inside.

With each scene, the film dives deeper into Borg’s consciousness and his developing understanding of his own guilt. Some dreams reveal themselves as mere visions, Borg as a wallflower spectator to the theater of the past. They grow increasingly surreal and engaging. In one scene, the characters move Borg through the dream-world (or nightmare world) and seat him down at a (literal) courtroom trial of his subconscious.

What impressed me so much about the film was this sort of audacity; the audacity to dive so intimately into the internal. We watch Borg experience his feelings and realizations, just short of him being able to piece together the words for how to describe his change. This indescribable process of rediscovering what once brought you joy and chipping away at the realization of what is important in life beyond superficial things felt so real. Working with a concept that could easily have felt too on-the-nose, Bergman distills it into simple and elegant imagery. The elegance of the film could also be credited to the actors, who perform with great subtlety. Each character that moves around Borg adds real weight to the scenes. After some time together, their friendships grow, filling in the chilly feeling of loneliness at the beginning of the film.

I would recommend this film to anyone. It hit me so hard, even as a young person, feeling directly interrogated about my fear of getting older and my aversion to self-criticism. I left this movie genuinely wanting to both cry and smile, with a renewed compassion for myself and the people around me. It’s a beautiful movie. Put it on your lists.

The Charles Revival Series screens repertory films each week. If you’re in the mood for hidden gems, pick a film you’ve never heard of and go check it out.