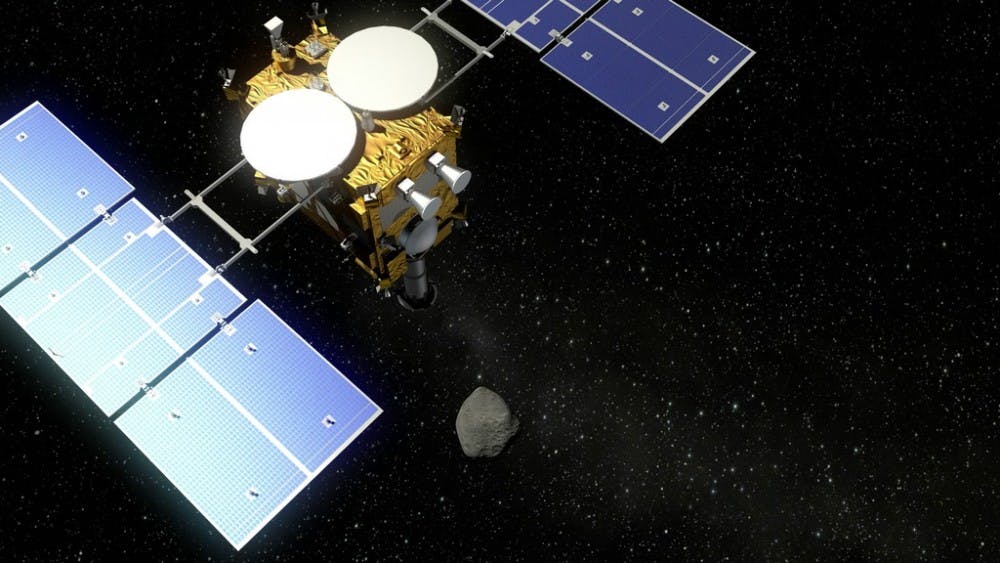

The Hayabusa2 spacecraft finally landed on the near-Earth asteroid Ryugu on Feb. 21, 2019. This was no easy feat. The Hayabusa2’s main body measures about 1 x 1.25 x 1.6 meters (m) in size and weighs 609 kilograms (kg). Launched in December 2014, Hayabusa2 managed to land as planned about four years later on an asteroid no bigger than one kilometer (km) in diameter, orbiting over hundreds of millions of kilometers away from earth.

This mission, headed by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), aims to return samples from this asteroid to Earth.

Ryugu is a C-type, or carbonaceous, asteroid, meaning it is composed of carbon compounds, silicates, oxides, sulfides and water. They are the most common type of asteroid, but this would be the first time samples from a carbonaceous asteroid are returned if the mission is successful.

Some meteorites of this type, such as the Murchison meteorite, have even been found to contain nucleobases and amino acids, important biological building blocks of life.

The predecessor to Hayabusa2, Hayabusa, managed to collect some dust from an S-type, (siliceous) asteroid known as Itokawa years earlier, returning by 2010. This mission did face some unexpected challenges, including power outages, communication errors and failures in some of its collection mechanisms. The team learned from these mistakes and improved their design to carry out this new mission.

Now that it has reached Ryugu, Hayabusa2 must collect samples from both the surface and subsurface of the asteroid.

The spacecraft is outfitted with a number of devices including cameras, a laser altimeter, infrared spectrometers and even a few robots to help it survey the asteroid. These robots include small independent rovers that are deployed to further explore and measure data from the surface.

The Hayabusa2 itself is powered by large solar panels and uses this energy to operate its ion thrusters, which are needed to propel itself back to Earth.

To collect samples from below the surface, Hayabusa2 will blow a crater into the asteroid using a small carry-on impactor. This device is capable of accelerating a two kilogram mass of copper up to a speed of two kilometers per second within a millisecond to penetrate the surface of the asteroid. After landing in this crater, the spacecraft must trap Ryugu’s matter and bring it back home.

If all goes well, the Hayabusa2 will depart the asteroid later this year and return to Earth by late 2020. If successful, the mission could give a glimpse into the conditions of the early solar system that fostered life’s origins.

Ryugu is an asteroid believed to be formed much earlier than Itokawa, potentially containing materials from the early state of our solar system over 4.6 billion years ago. Patrick Michel, the mission’s co-investigator from the Côte d’Azur Observatory, believes the data from the asteroid samples can shine light into the origins of life on Earth.

“One scenario could be that all the elements needed for the emergence of life, including water and maybe other prebiotic materials, were brought by these small bodies,” Michel said, according to Scientific American.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is also undergoing a similar mission with OSIRIS-REx. This spacecraft launched in 2016 and is also planned to return samples from another near-Earth carbonaceous asteroid called Bennu sometime in 2021.

Randall Elkind, a junior at Hopkins working on a design project to collect space dust in the mesosphere using a novel device in the external payload of a rocket, weighed in on these space missions in an interview with The News-Letter.

“I think it’s fascinating how these discoveries made from objects millions of miles away in space can tell us about our own history. It’s going to be interesting to see how these discoveries will inspire and motivate new lines of space research and experimentation. Hopefully the results will begin to merge the boundaries between biological studies and space exploration,” Elkind said.