Since childhood, art museums were my safe space. They were hushed and contemplative, a place for solitary reflection as well as interesting (murmured) discussion. It started with encouragement from my parents. My dad is an artist and my mother an avid art lover, so they made it a priority to expose me to art as early as possible.

My dad made flash cards out of famous works of art and would go over them with me. “Picasso” he would say aloud, holding up a laminated copy of a colorful, distorted face. Then “Matisse,” and “Monet.” He loves telling the story of the first time I went up to a Sunflowers magnet on our fridge (next to a magnet of The Dance that now resides in my apartment) and pointed at it, declaring “Van Gogh.”

I had children’s books narrated by famous artists, explaining their histories and styles. The Salvador Dalí one stands out in my mind, a little cartoon Dalí with a long nose and expressive mustache gesturing to images of melting clocks and chopped up body parts. I was absolutely enthralled.

Still, none of that compared to the impact that going to the museum had on me. I don’t necessarily remember those really early museum trips, but I remember discovering that an art museum was a place of magic. It fostered a sense of awe and wonder that I’d carry with me as I grew up.

I do have many vivid memories of visiting when I was bit older, though. There was the time I leaned down over one of Warhol’s Brillo Boxes, an early start to my career of getting dangerously near priceless pieces of art just so I can see their tiny details.

I pressed myself up against the wall the first time I saw one of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, looking at it sideways so as to see how far the thick, clumped oil paint rose off of the canvas. I cried the first time I saw Matisse’s The Dance in person, its huge stature completely dwarfing my family’s tiny magnet.

In many ways, I still have that wide-eyed kid in me. One of my favorite things to do is to visit the BMA on days that I am particularly overwhelmed, wandering around my favorite rooms and making the security guards nervous as I bring my face terrifyingly close in order to admire the rippling clothes and astonishingly flesh-like bodies of marble sculptures. I always keep up with new exhibitions opening and hang prints all over the walls of my apartment. I even hope to get a Keith Haring tattoo soon, a tribute to my favorite street artist.

But I’m older now, and while art museums do provide a place for me to escape—which I am forever grateful for—they can also often become a place of exclusion and, at their worst, violence.

So far, I have not mentioned a single female artist. There’s a good chance you didn’t even notice. And why would you? Many museums don’t seem to notice when they exclude women, either. But museums are, for many, a main source of art education. Though they are often panned as elitist institutions (a valid criticism for a good number of them), there are still quite a few, like the BMA, that are open and free to the public, providing for everyone.

Yet, when museums don’t take this responsibility seriously, things can fall through the cracks. Usually, these “things” turn out to be female artists and artists of color. Though I have plenty to say about this, it’s all mostly been said by the art collective “Guerrilla Girls,” a group of women who don gorilla masks and create pieces that call out the art world for bias against women and artists of color.

Beyond this exclusion, though, is a more complex issue. I think most people can agree that women should be included in art museums mores. But how do we approach the more unsavory art that does hang in museums instead?

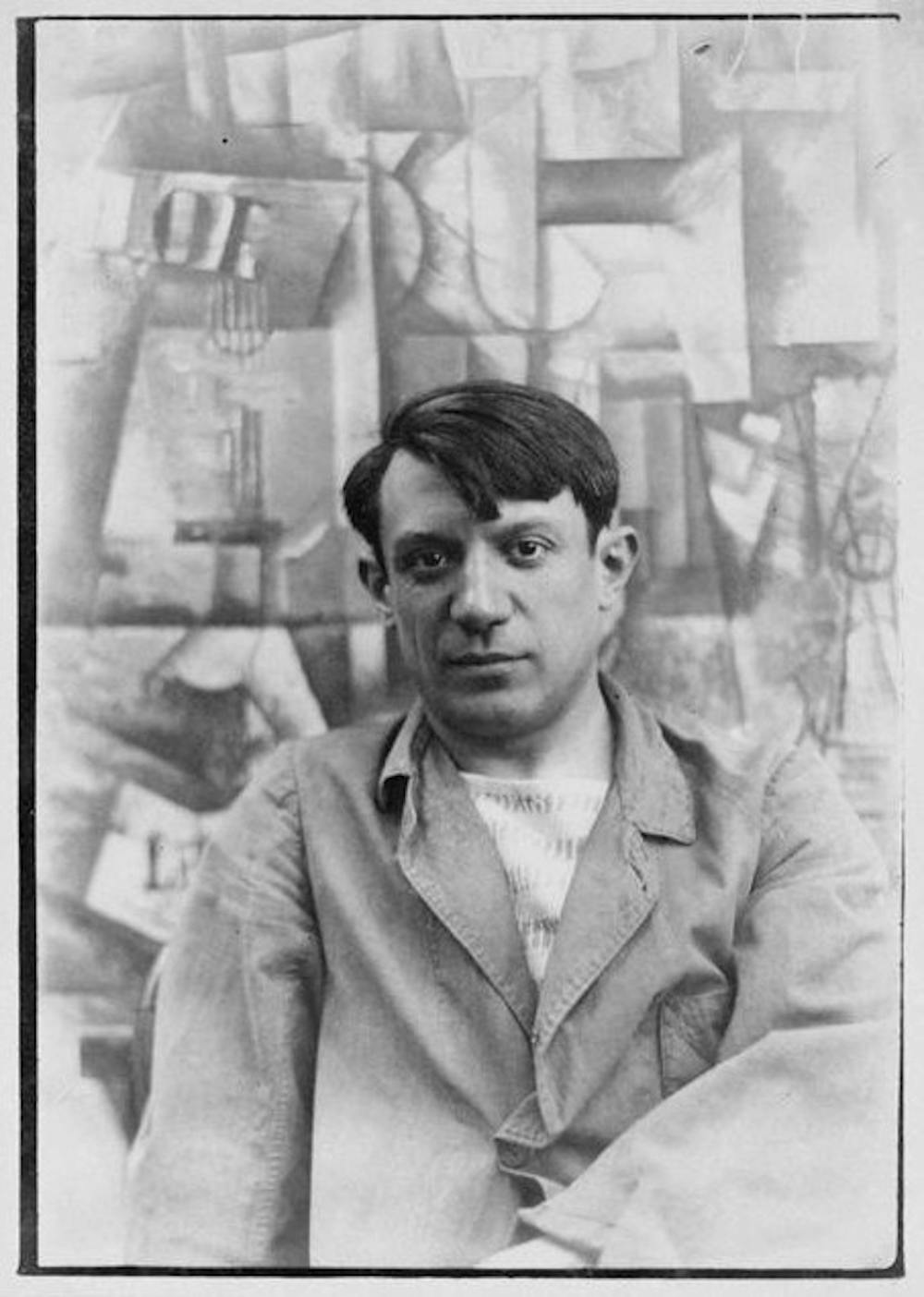

Picasso once said, “For me there are only two kinds of women, goddesses and doormats,” and he was well known for his emotional abuse of his partners. This vitriol can be seen in his paintings of the minotaur, generally known to represent him, raping women. Paul Gauguin was a pedophile who took underage Tahitian girls as his sex slaves, using them as the inspiration and models for some of his most significant pieces. And these men are not unusual cases. Walk around any art museum and you'll find the work of fascists, racists, anti-Semites, rapists, and abusers abounds.

Of course, this isn’t just a problem that plagues the art world. We’re obviously most aware of those in Hollywood currently, with the #MeToo movement exposing abusers left and right. But there’s also the messed-up authors of literary canon, i.e. Bukowski the aggressive misogynist, Pound the virulent Nazi supporter, Ginsberg the NAMBLA member—and those are just a few of the poets, let alone the novelists. And the same goes for other creative industries, like music and fashion.

People say to “separate the art from the artist,” and maybe this works for some artistic mediums (though I’m not really convinced). But how can I be expected to stand in front of a Gauguin painting and not feel uncomfortable staring at the naked image of an enslaved teenager? How can I be asked to ignore the exposed forms of women who faced emotional and physical mistreatment, their nude bodies immortalized by their abuser? Especially when they are surrounded by so many other frozen women who shared similar experiences, devoid of a female point of view to counter such objectification.

In addition to the abusers, we have to deal with those with dangerous political ideologies. For many, visual art is a political vehicle, as evidenced by the Dadaist, Muralist, and Surrealist movements. How are we to then ignore the political messages behind other political art movements that haven't aged quite as well, like the Futurists? What about the specific artists who held terrible personal views? Are we meant to pick and choose which of their pieces are political and which are not?

The answers to these questions are borderline impossible to universally agree upon. Everyone has an opinion, and museums are stuck attempting to contend with all of them, often resulting in them contending with none.

I won’t pretend to have a magic answer to the sticky ethical mess that is reconciling the love of someone’s art with that someone’s personal legacy. But I do know this: art museums have a responsibility to the public. They are a place of education and enrichment. It’s about time they start educating people on the artists they are idolizing. Then, at the very least, visitors can choose for themselves if they really can “separate the art from the artist.”

From an early age, art museums were where I would go when I was scared or confused or just needed some time alone. I turned to them for safety, peace, and, many times, a sense of wonder. And I still do that. But it’s impossible to ignore that, as I’ve grown up and faced the challenges and pain that women do, and became more aware of social issues at large, there are pieces that I don’t stand in front of for very long anymore, giving a passing glance to artists whose behavior has dulled the shine of their art.