Based on the media’s depiction of young adults, one would think that all college and high school students are having a lot of sex all the time. There are entire TV shows that focus on the sex lives of teenagers. But recent survey data seem to suggest that people are having a lot less sex than we think they are.

According to the national Youth Risk Behavior Survey, the percentage of high school students who have ever had sex declined from 54 percent in 1991 to 39.5 percent in 2017. Since 2007, the percentages of high schoolers who have had four or more sexual partners and who are currently sexually active have also decreased.

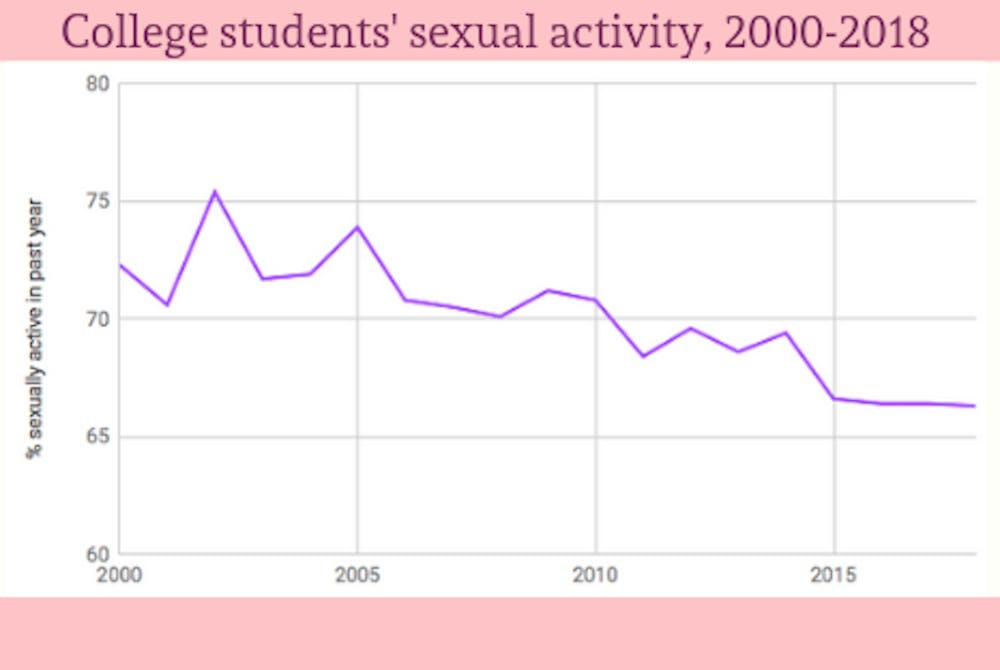

The results are similar for college students. The 2018 National College Health Assessment found that only 66 percent of students had sex in the past 12 months, compared to 72 percent in the 2000 assessment. This trend holds true for Hopkins students; The News-Letter’s recent survey found that about 67 percent of students are sexually active.

Taken as a whole, the data seem to show that fewer young people are having sex today than they were a decade or two ago, and even those who are having less of it. Publications like The Atlantic, Cosmopolitan and Tonic have picked up on this trend, publishing articles that attempt to determine the factors behind it and to examine its possible implications.

The Atlantic, which labeled this phenomenon the “sex recession,” speculates that young people may be prioritizing their education and career over their sex lives, and thus are waiting longer to partner up. This is consistent with data from the U.S. Census Bureau, which found that the median age at first marriage has increased from 24 and 26 in 1990 for women and men, respectively to 28 and 30 in 2018.

Chris Kraft, director of clinical services at the Johns Hopkins Sex and Gender Clinic, agrees that this theory may be valid. He added that delaying finding a relationship may make it more difficult to secure one later on.

“There’s some people that genuinely don’t want to be in relationships at certain stages in their lives, particularly when people are in college or school, and they’re going to be moving for school or for their career. I’ve seen people say, ‘this is not a time to be in a relationship,’” he said. “But then I’ve seen other people who have gotten into their careers, they’ll say, ‘I’d really like a relationship now,’ but it’s hard to find one.”

The Atlantic also theorizes that increased access to technology may be impairing people’s social skills and making it more difficult and inconvenient to find sex partners. With the rise of internet porn, there’s a reduced need to find sexual satisfaction in the real world. This is consistent with data showing that the percentage of men and women who masturbate has risen dramatically in recent years.

Although Kraft believes there has been a positive shift toward more acceptance of masturbation and pornography, he is worried that the decreasing prevalence of partnered sex may result in greater loneliness and isolation, potentially leading to depression and anxiety.

“It’s harder to form relationships or people are delaying having relationships,” he said. “And then they don’t develop social skills because they’re too isolated and lonely to actually connect with people, so it’s kind of a negative feedback loop.”

Some researchers, however, have refuted the claim that Americans really are having less sex. They point out that many of the surveys that collect data on sexual activity don’t define what counts as sex. Does oral or anal sex count? What about mutual masturbation? The Youth Risk Behavior Survey considers only “sexual intercourse,” while the National College Health Assessment asks about “oral, vaginal and anal” sex. Data suggest that oral and anal sex have been increasing in popularity since the early 90’s, so maybe it’s not that we’re having less sex — it’s just taking a different form.

Whatever the causes or implications of this so-called “sex recession,” there isn’t necessarily cause for alarm. There are still plenty of people who are able to find relationships and sex partners, and public perceptions of sex and sexuality continue to grow more progressive. In particular, Kraft noted that he has seen a significant positive change in the way women can express themselves sexually.

“If women choose to be casual, that can be seen as a positive and not as a negative,” he said. “There’s still a double standard, and it still can get much better, but I’ve seen a change in women being able to express their sexuality and talk about their sexuality.”

Or perhaps, as both Kraft and The Atlantic suggest, the #MeToo movement and today’s lower tolerance for sexual assault and coercive sex might partially explain this phenomenon. It’s possible that in recent years, people have felt more empowered to refuse sex they don’t want to have. To Kraft, this is a potential benefit of the sex recession.

“One of the benefits to not being [as] sexual is that when people are sexual, it’s probably better,” he said. “Having less sex could be a part of some trend where people are being sexual and intimate with partners when it’s best for them. And they’re hopefully more satisfied.”