For as long as I can remember, I have loved reading. But, just like everyone else in my classes, I never really enjoyed the books we were required to read. I never understood why the only books we could supposedly learn something from were dusty pieces of literature that I found boring or irrelevant. That is, until I took AP Lit in my senior year of high school, when my teacher gave us all a summer reading assignment that I could not put down.

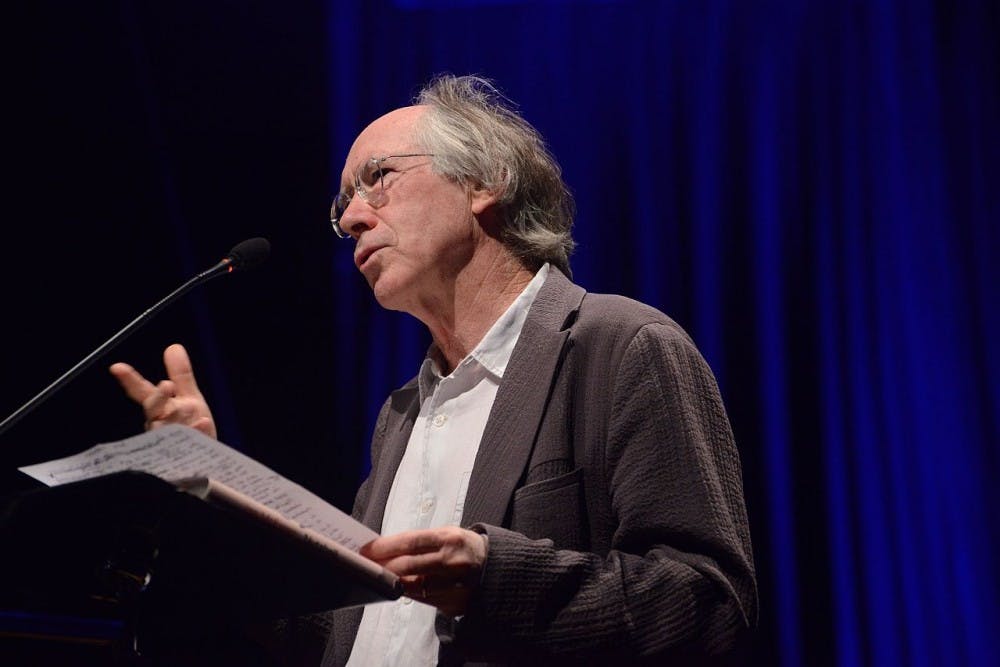

For the first time, I wanted to finish a book for school quickly not because I had a deadline to meet but because I was genuinely wrapped up in what was at stake for its characters. That book was Atonement by Ian McEwan.

Thus, I started my senior year excited to discuss the multiple twists in the book, and I had a new author whose work I wanted to explore further. My search for more Ian McEwan books led me to pick up a copy of The Children Act from the used book sale at my local library.

The Children Act follows a High Court Justice in England’s Family Court named Fiona. At the novel’s start, Fiona is having marital problems with her husband Jack, who misses having sex and asks for Fiona’s permission for “one last fling” with a younger woman he knows from his office. Thus Fiona is driven to dive deeper into her work.

Simultaneously she is presented with the intriguing case of an almost-18-year-old boy named Adam who, because of his religion, is refusing life-saving cancer treatment. However, because he technically is still shy of his 18th birthday, a hospital sues him and his parents in an effort to force him to receive treatment.

Yet, his condition is so serious that Fiona only has three days to review the information related to the case before she must make a decision on whether or not he must receive treatment. It’s a plot similar to My Sister’s Keeper by Jodi Picoult but minus the extra siblings and with the addition of a religious element, as Adam and his family are strict Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Adam, his parents and his religious community insist that he is exceptionally mature for his age and fully aware of his imminent death. They argue that this means that he should be allowed to make his own decision about what happens to him. This leaves the reader in the position of having to make up their own mind.

Fiona insists that in order to make her decision, she must meet Adam in person rather than deciding based solely on what she has been presented on paper. For some reason that is intangible to both Fiona (and to me as a reader), she feels an undeniable pull towards this case and resonates with the boy’s situation.

Although the main character of the novel is definitely Fiona, the impact of Adam’s case on her life is immense. This is in large part due to the fact that it forces Fiona — and, by extension, McEwan’s readers — to reckon with some of the “big questions” of life that we often try to ignore, especially when it comes to religion and spirituality.

I don’t consider myself to be all that religious. Still, The Children Act led me to consider several of these questions. What role does God play in our everyday lives? Do we have the right to make judgments about each other’s beliefs or to determine what should happen to certain people based on their faith?

Ultimately, I don’t think so. Yet, what if your faith, as in Adam’s case, works against what might be seen by the general public as your physical body’s best interests? This, I think, is where things get a little more complicated.

Is a decision like Adam’s brave? Admirable? Foolish? All of the above? How does Adam’s age affect readers’ judgments? What if the same decision was being made by someone older than him?

McEwan raises a lot of questions not only about medical ethics, but also about our nature as human beings and our abilities to make judgments. As seen through the eyes of Fiona, who is in a position of relative power, such existential questions hold even more weight.

In addition to McEwan’s treatment of religiosity, he also addresses the pressures and insecurities around women’s decisions to become mothers (or not to). At over 50, Fiona and her husband Jack aren’t seeing eye to eye. This prompts her to wonder how things might have been different if she and Jack had children. I appreciate that the novel’s protagonist is an older married woman who never had children.

McEwan artfully depicts how Fiona is forced to face the stigma that comes with a childless status. This is just one of the many reasons that I found The Children Act to be a complex, engaging exploration of a range of subjects, many of which don’t prompt clear-cut answers, which only makes them all the more interesting.