The Walters Art Museum in Mount Vernon opened their newest exhibition, Transformation: Art of the Americas, on Sunday, Oct. 27. As described on the installation’s webpage, Transformation spotlights roughly 20 objects from indigenous American cultures that display the metamorphosis of body and spirit. Name a more wholesome Halloweekend activity than attending a gallery on its first day, I dare you.

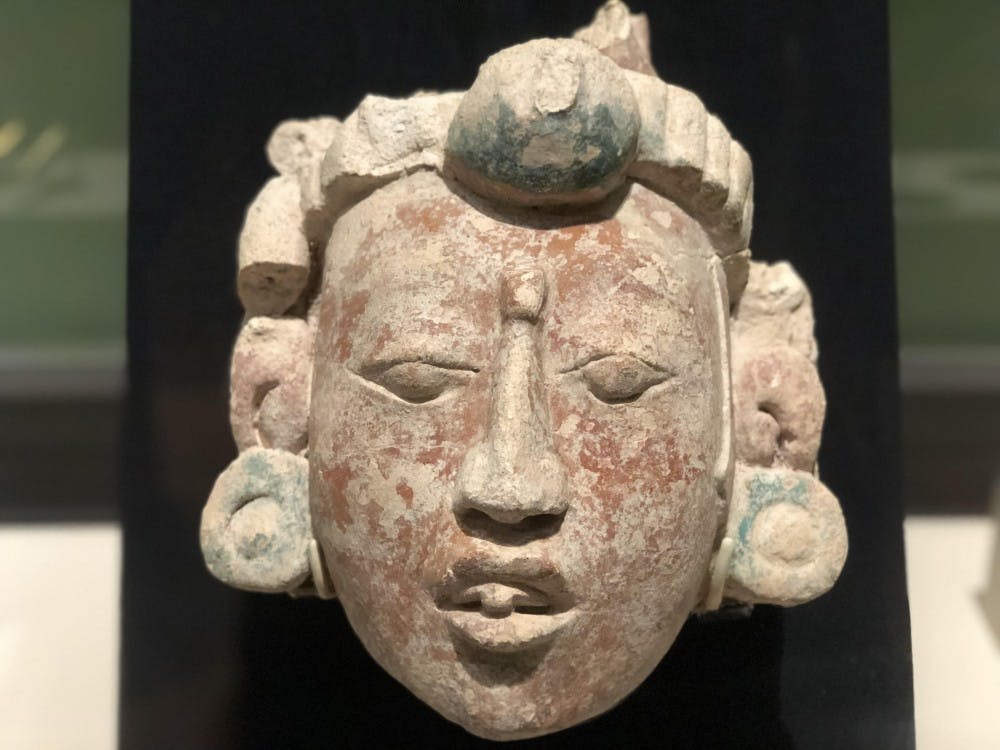

The objects featured in Transformation included gold jewelry, stone sculptures and a painted ceramic burial urn. According to the exhibit, they exemplified a worldview of pre-colonial America: “that states of being — human, animal and divine — were fluid and interchangeable.” Native Americans altered their bodies in order to imitate and take on the characteristics of powerful predators, deities and supernatural beings.

Some adorned their ears, tongues and cheeks with polished accessories so that they would shine like the gods. Two portrait heads on display demonstrated how infants’ skulls were reshaped by being pressed between boards. For certain Native American peoples, changing the body meant changing the soul.

Native Americans performed elaborate rituals in the name of spiritual transformation. These rituals incorporated costumes, music and dance, as well as alcohol and hallucinogens that Native Americans believed would grant them entry to transcendent headspaces and sacred realms, like chicha — an Andean chili-spiced corn beer — and the yagé vine, a hallucinogenic plant that indigenous Ecuadorians snorted.

I especially enjoyed a machine that allowed goers to hear the sounds made by three exhibited instruments that could have been a part of those rituals: a flute, a whistle and an ocarina — an ancient wind musical instrument. The friend with whom I went particularly liked the metallic statuettes depicting indigenous people’s deities.

Overall, we found that being able to see and learn about artifacts crafted between 1500 B.C. and A.D. 1500 by one of the country’s most marginalized ethnic groups was a truly valuable experience. But we wished there had been more artwork, as the entire installation was confined to one small room.

My friend agreed that the size of the installation was an issue.

“The exhibit highlighted the myth of the vanishing Indian trope,” she said. “Compared to other displays, it was miniscule and forgettable. Native American heritage and culture are often not seen in society, and while I was grateful they had any representation at all, it could have been much more.”

Perhaps a saving grace of the exhibit was part of a description written at its entrance: “As you view these works of art, you are invited to reflect on your own mental and physical transformations.”

This message reminds me not of a transformation that I experienced but of one that someone who attended my high school experienced. A few years ago, she came out as transgender on Facebook.

“As some of you may remember, I wore a dress on Halloween. If you asked me about it, I probably told you that I was ‘Myself, from an alternate universe,’” she wrote. “‘What I didn’t mention is that I’d prefer to be in that universe where I was assigned female at birth.’”

She explained that, while she had been assigned male at birth, she identified as female.

“I am a girl,” she wrote.

In light of the Trump administration being poised to define the word “transgender” out of existence, I think our country could learn something important from the philosophy of its original inhabitants, many of whom celebrated the fluidity of states of being. I think a lesson we can apply from Transformations is that gender and sex are distinct. Gender is not biological sex at birth and should not be determined by genitals. No, gender expression is not the same as putting on a Halloween costume, but gender can be fluid.

Of course, conversations about cultural appropriation are especially important to have during the Halloween season, and I don’t want to appropriate Native American culture. (To be clear, I have little knowledge of how Native Americans interpreted issues of sex and gender.) As I wrote above, changing the body meant changing the soul for several Native Americans. But the body and the soul are not tied together; neither are gender and sex. Sex reassignment surgery can be empowering for some, but it can also be traumatizing for others. It can affirm someone’s gender identity but also provoke internalized transphobia.

Gender and sex (i.e. genitals) are inextricably related, but they are not synonymous for everyone. Mental and physical transformations are connected but not the same.

It goes without saying that identity is a nuanced issue that warrants a great deal of discussion and exploration. “Transformation” offers a good starting place.

Curated by Ellen Hoobler, William B. Ziff, Jr., Associate Curator of the Americas, 1200 BCE – 1500 CE, with Verónica Betancourt, Manager of Gallery Learning, Transformation runs at the Walters until Oct. 6, 2019.