Researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden, in collaboration with researchers at the University of New South Wales, have recently discovered a new structure in human cells. The study detailing the procedures and outcomes was published in the journal Nature Cell Biology.

The discovered structure is a new type of protein complex that can be used by human cells to attach to their surroundings. This structure has proved to be a key component involved in cell division.

The cells found in tissue are surrounded by a net-like structure called the extracellular matrix. Cells make use of receptor molecules on their surfaces, which have control over the assembly of large protein complexes within the cell, in order to attach themselves to the matrix.

Adhesion complexes allow for the exterior to be connected to the interior of the cell. They also have the ability to signal the cell and communicate information about its immediate environment, which allows the cell to adjust its properties based on the situation. This signaled information helps the cells arrange themselves, coordinate their functions, and even know when to grow and when to die. As a whole, cells with an adhesive capacity do not just relay messages between the cells in a tissue; they also help physically join cells to one another.

Additionally, adhesion represents the mechanism behind how cells interact with one another. These interactions are based on molecule reactions at the surface of the cells.

Therefore, the adhesion complexes are a crucial part of multicellular structural maintenance, and it serves as a foundation for multicellular organisms because it contributes to the structure and function of tissues.

Previously known adhesion complexes in mammals include cadherins (calcium-dependent glycoproteins), integrins (receptor proteins that span the membrane of a cell that are not dependent on calcium), immunoglobulin superfamily members (molecules involved in cell adhesion with an immunoglobulin region that are not dependent on calcium) and selectins (single-chained glycoproteins that are calcium-dependent).

The protein complex discovered by researchers at Karolinska Institutet and the University of New South Wales was a new type of adhesion complex with a unique molecular composition that sets it apart from previously discovered complexes.

Staffan Strömblad, the principal investigator of the study and a professor at the Department of Biosciences and Nutrition at Karolinska Institutet, shared his excitement for the discovery in a press release.

“It’s incredibly surprising that there’s a new cell structure left to discover in 2018,” Strömblad said. “The existence of this type of adhesion complex has completely passed us by.”

The newly discovered adhesion complex provides the opportunity for researchers to address how cells remain attached to the matrix during cell division. This question could not have been answered in the past, given that the previously known adhesion complexes dissolve during cell division in order to allow the process to go forward. However, Strömblad found that this new type of adhesion complex does not follow the same trend.

“We’ve shown that this new adhesion complex remains and attaches the cell during cell division,” Strömblad said.

The researchers were also able to show that the newly discovered adhesion complex has control over the ability of daughter cells to occupy the correct place after cell division. They were able to determine this because the daughter cells ended up in the wrong place when the researchers blocked the adhesion complex.

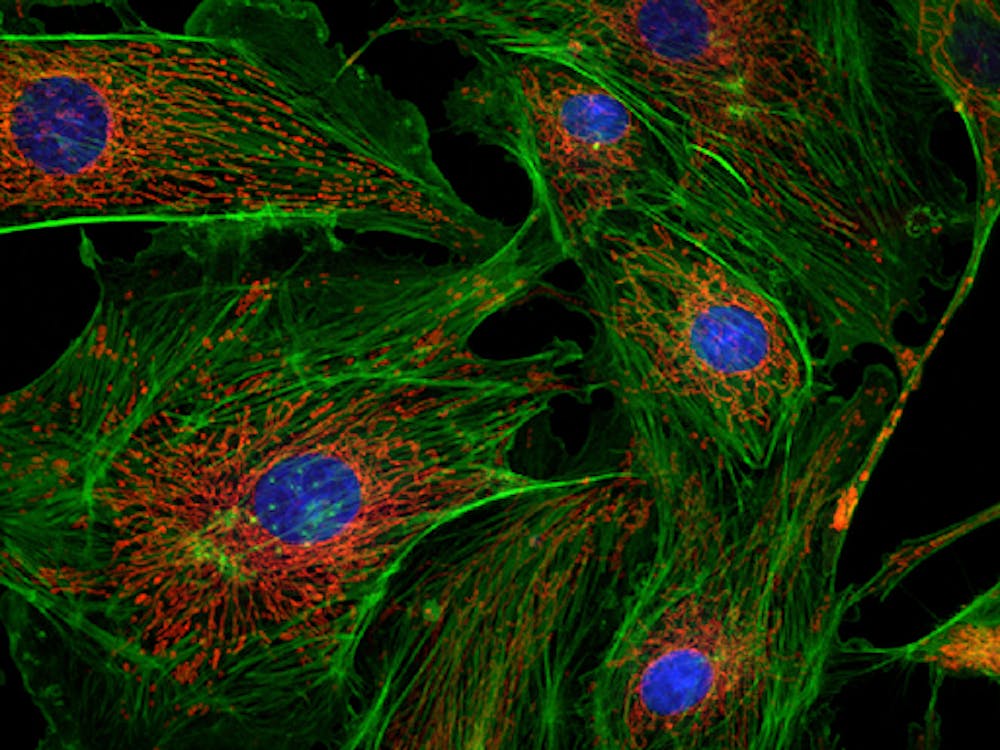

The researchers performed the study on human cell lines mainly through the use of confocal microscopy and mass spectrometry. However, Strömblad believe that further research must be carried out in order examine the role and behavior of the new adhesion complex within living organisms.

“Our findings raise many new and important questions about the presence and function of these structures,” Strömblad said. “We believe that they’re also involved in other processes than cell division, but this remains to be discovered.”

The researchers have decided to call this newly discovered adhesion complex “reticular adhesions” with the intention of reflecting their net-like form.