The Women Faculty Forum at Homewood invited the Hopkins community to discuss sexual harassment in academia on Thursday, Oct. 25 in the Mudd Atrium. The Forum encouraged faculty members, graduate students and undergraduate students to explore ways to improve gender equity in the fields of academic sciences, engineering and medicine.

Participants discussed the report released by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, which brings to light the sexual harassment that women face. They also addressed the implications of the report’s findings on the Hopkins academic community. The report examined how sexual harassment negatively impacts women pursuing scientific, technical and medical careers as well as policies best suited to preventing it in these fields.

Women Faculty Forum Co-Chair and Biophysics Professor Karen Fleming gave participants an overview of the report and emphasized the changes that it could bring to academic culture.

“We have been given a gift,“ she said. “It contains a ton of data, so we can all have a conversation that’s evidence-based. We can’t expect change unless we have data to make change with.”

Fleming explained that the report helped validate the struggles that many women, people of color and people belonging to other minority groups face. According to Fleming, the data could help show them that they are not alone, though she critiqued the report for focusing predominantly on the experiences of white women.

The climate that this harassment creates, she stated, causes more women to leave scientific fields. She described that at each stage of academic transition — for instance, between high school and undergraduate or undergraduate and graduate school — scientific fields lose women.

“Women are dropping out of science. People of color are dropping out of science. The demographics of practicing scientists is not representative of the demographics of the population,” Fleming said.

Fleming used the metaphor of a pipeline to explain why women drop out of scientific fields at different points during their academic careers. She pointed out that when a pipeline breaks and water spills out, the pipeline — not the water — would be at fault.

“Women aren’t leaving necessarily because they choose to,” she said. “It’s not the women that are the problem, it’s the pipeline.”

Fleming further explained that hierarchical power structures inherent in academic institutions allow sexual harassment to take place more often. She pointed out that hostile conditions often occur in laboratories, where principal investigators (PIs) are in charge of student researchers.

Senior Sam Gomes agreed, describing situations where her peers had experienced gender-based harassment during their research experiences.

“After learning about the types of gender harassment that can take place in an academic setting, I realized that a lot of my friends’ complaints about their lab PIs and professors were actually complaints of gender harassment,” she said.

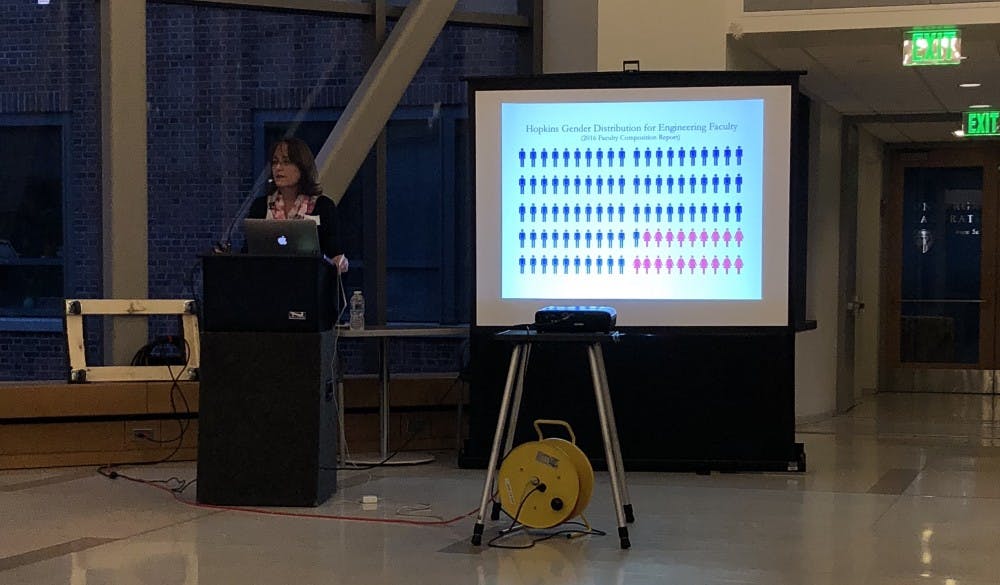

Fleming added that male-dominated environments create a perception that sexual harassment can be tolerated. She quoted figures from the University’s Report on Faculty Composition and explained that during the fall of 2015, 81 percent of engineering faculty, 75 percent of natural sciences faculty and 68 percent of social sciences faculty were male.

Physics & Astronomy (PhA) graduate student Michael Busch also noted the gender disparity among students studying physics. He explained that PhA tends to be a nationally male-dominated field. Women comprised just under 20 percent of PhD recipients in 2017, according the American Physical Society. According to Busch, the department at Hopkins follows the same trends.

“At the graduate level we have about 20 percent women graduate students... We are doing pretty badly,” Busch wrote in an email to The News-Letter. “When you bring this fact up to anyone in the Physics community that could actually make changes, the response is typically, ‘Well, we’re doing as badly as everyone else, right?’”

He acknowledged that though the University’s PhA department makes significant efforts to improve the environment and make it more welcoming for women, graduate student admission and faculty composition statistics still show a male-dominated environment.

He wrote that he once observed a male student in his department tell a female student that women were genetically less capable of studying scientific fields.

“I reported this incident to my program administrator along with another fellow student witness and almost took it to the department chair but was told not to,” he wrote. “I’m not sure it was ever handled.”

Fleming explained that though the federal guidelines specified in Title IX aim to prevent gender-based discrimination, institutions tend to comply only symbolically with the guidelines. She added that institutions adhere to Title IX to protect themselves from liability but make very little effort to actually prevent sexual harassment.

Busch agreed, adding that he and some other participants felt uncomfortable seeing Office of Institutional Equity (OIE) staff members at the event. OIE is responsible for addressing cases of discrimination and sexual violence under Title IX.

“The professor sitting next to me... [explained] how OIE had mishandled her case: that multiple people had accused her harasser — another professor — of gender harassment and that OIE had treated each case separately, closed each one, and told the victims that they could not do anything about it,” he wrote.

He said that one of the OIE representatives responded to the professor saying that the specific policies regarding how OIE had treated the professor’s case had changed since and that they still encouraged Hopkins community members to report any instances of sexual harassment.

“This did not assuage anyone,“ he wrote.

Fleming felt that those who attended the discussion had a responsibility to hold their institutions accountable and make a change for future generations. To Fleming, the data showed that change was necessary.

“One of the most important and shocking findings from the study is the fact that 58 percent of female academic faculty and staff have experienced some sort of sexual harassment,” she said. “We cannot keep doing the same thing. It is never going to change. We have to do something different.”

After Fleming’s presentation, participants broke up into groups to discuss their experiences and potential methods to reduce gender-based harassment.

The conditions included diffusing the hierarchical and dependent relationship between trainees and faculties and moving beyond legal compliance to address the culture and climate in which sexual and gender harassment occur in.

Solutions that the groups came up with included: providing mentoring to researchers at all levels; creating spaces for faculty, post-doctorates and graduate students to socialize within departments; and increasing the accessibility to resources for victims of sexual and gender harassment.

Junior Michelle Lu appreciated that professors were involved because it showed that they cared about addressing the issues raised at the event.

“It was cool seeing all the professors come here and see that they’re pretty invested in the process,” Lu said. “People are doing pretty good work at Hopkins even though it’s not perfect yet.”