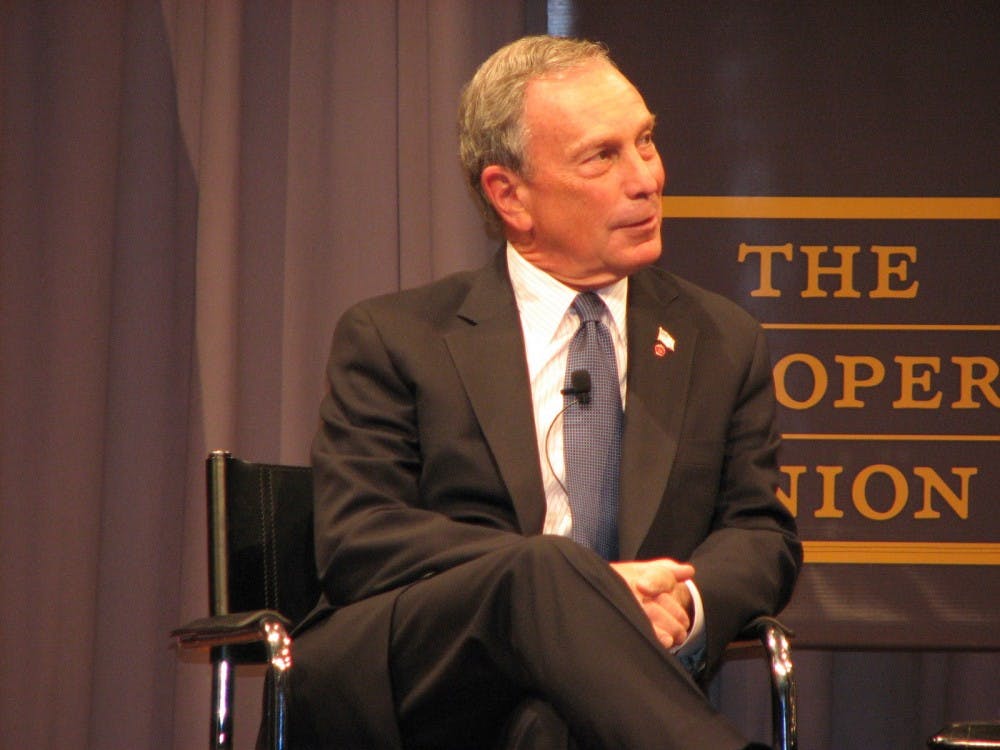

Over Thanksgiving break, former New York Mayor and Hopkins alumnus Michael Bloomberg announced that he would donate $1.8 billion to financial aid, specifically benefitting low and middle-income students. The donation will allow the University to be a loan-free and permanently need-blind school, and will help Hopkins recruit and support more low-income and first-generation students.

As Hopkins students, we are truly grateful for this donation – especially for those of us who rely on financial aid to attend school each year. We appreciate that our school is making real efforts to become more socioeconomically diverse. In April, we asked University President Ronald J. Daniels what steps University officials have taken or plan to take to ensure that students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds have the same opportunities to work and learn here at Hopkins.

“Students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds don’t tend to make their way to universities of the stature of Johns Hopkins,” Daniels said. “You have to find easier pathways to bring them to the University.”

With Bloomberg’s gift, we believe that the University will now have the means to recruit and attract more students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Yet, we recognize that we cannot be blinded by the size of the donation. The donation masks a much larger problem: that students who are low-income and/or first-generation face many barriers in their attempts to pursue higher education. The resources that enable students to have the “merit” to get into elite institutions – high test scores, extracurriculars, a quality education – are expensive.

There is no denying that Bloomberg’s donation will provide substantial benefits for the low-income students here and low-income students to come. But we have to face that adding to the University’s already sizable endowment also reinforces the divide between private “elite” institutions like Hopkins and public universities. In the U.S., elite universities tend to have more money and receive more donations. In 2017, Hopkins had an endowment of $3.8 billion. Harvard’s endowment totaled $37.1 billion. On the other hand, the University of Maryland, Baltimore County – a public research university – had an endowment of $80.7 million.

A $1.8 billion donation does much to help the students here, and it does much to promote our University’s reputation and Bloomberg’s. But for low-income students across the country, it does little. We know that low-income students are less likely to graduate from college than wealthy students. In fact, according to a 2016 report from the Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education and The University of Pennsylvania Alliance for Higher Education and Democracy, 60 percent of students from the top socioeconomic quarter of households will graduate with bachelor’s degrees within 10 years. Only 15 percent of students from the bottom quarter will graduate with bachelor’s degrees in the same time.

In addition to our concerns about the attainability of higher education for low-income students, we also would like to address the praise that Bloomberg has received over the last week. On top of this generous donation, Bloomberg has contributed over $3.3 billion to Hopkins in his lifetime, and made other noteworthy contributions. He spearheaded the American Talent Initiative, which is an alliance of colleges and universities expanding access and opportunity for highly-talented low-income students, and became the nation’s leading unpaid gun control advocate in response to the 2012 Newtown shooting.

However, we should also remember Bloomberg’s staunch commitment to stop-and-frisk policing when he was mayor of New York City. Stop-and-frisk allows police officers to detain, question and search civilians for weapons. Under his term as mayor of New York City, the New York Civil Liberties Union reports that street stops increased by over 600 percent, and 87 percent of the people stopped were black or Latino, though they only comprise 4.7 percent of the city’s population. Although Bloomberg praises the efficacy of this policy, current data actually shows that it has little correlation to reducing crime. In addition to stop-and-frisk, we also have to consider how his policies, which pushed for people experiencing homelessness to become more self-reliant, led to a 61 percent increase in New Yorkers sleeping in homeless shelters while he was in office. His company, Bloomberg L.P., has also faced multiple sexual harassment allegations.

We are wary of putting Michael Bloomberg on a pedestal, despite his generosity, and hope that those calling for Bloomberg to announce his presidential candidacy will take a hard look at his policies. Similarly, we hope that our community examines the significance of philanthropy toward elite institutions and thinks about why these gifts are necessary to make education more accessible.

Martin Luther King Jr. once said: “Philanthropy is commendable, but it must not cause the philanthropist to overlook the circumstances of economic injustice which make philanthropy necessary.”

As we bask in the glow of Bloomberg’s generosity, we hope that students take Martin Luther King Jr.’s words to heart. We hope that our community is encouraged to have difficult conversations about socioeconomic and educational inequity. And we hope that we use Bloomberg’s donation as a springboard to think critically about the pervasive elitism and exclusivity in higher education. In order for our institution, and the American higher education system, to truly be accessible, much more work must be done to dismantle inequality. Bloomberg’s gift gives us the opportunity to begin asking how we can start.