The Office of Institutional Equity (OIE) released its first annual report containing data about the University’s handling of sexual misconduct and other forms of discrimination and harassment cases on Tuesday.

OIE, in accordance with Title IX, seeks to appropriately respond to reports of sexual misconduct, discrimination and harassment. The Office, which currently employs 13 full-time staff members, serves 25,513 students and 24,401 employees across all nine Hopkins campuses.

University President Ronald J. Daniels and Provost Sunil Kumar sent the OIE report in a schoolwide email about diversity at Hopkins. The report only included data for the 2017 calendar year.

Sexual Assault Resource Unit (SARU) Co-Director Mayuri Viswanathan appreciated the depth of data provided in the report, as well as the number of visuals it included. She felt, however, that it was not communicated well enough to the Hopkins community.

“From a student advocacy standpoint, having this data is a great starting point to have conversations with the administration. It gives us more of a grounding to bring up our concerns,” she said. “But they buried [the report] in the bottom of an email, and I think a lot of people missed it, so I wish it had been made more clear that it was part of the email they sent out.”

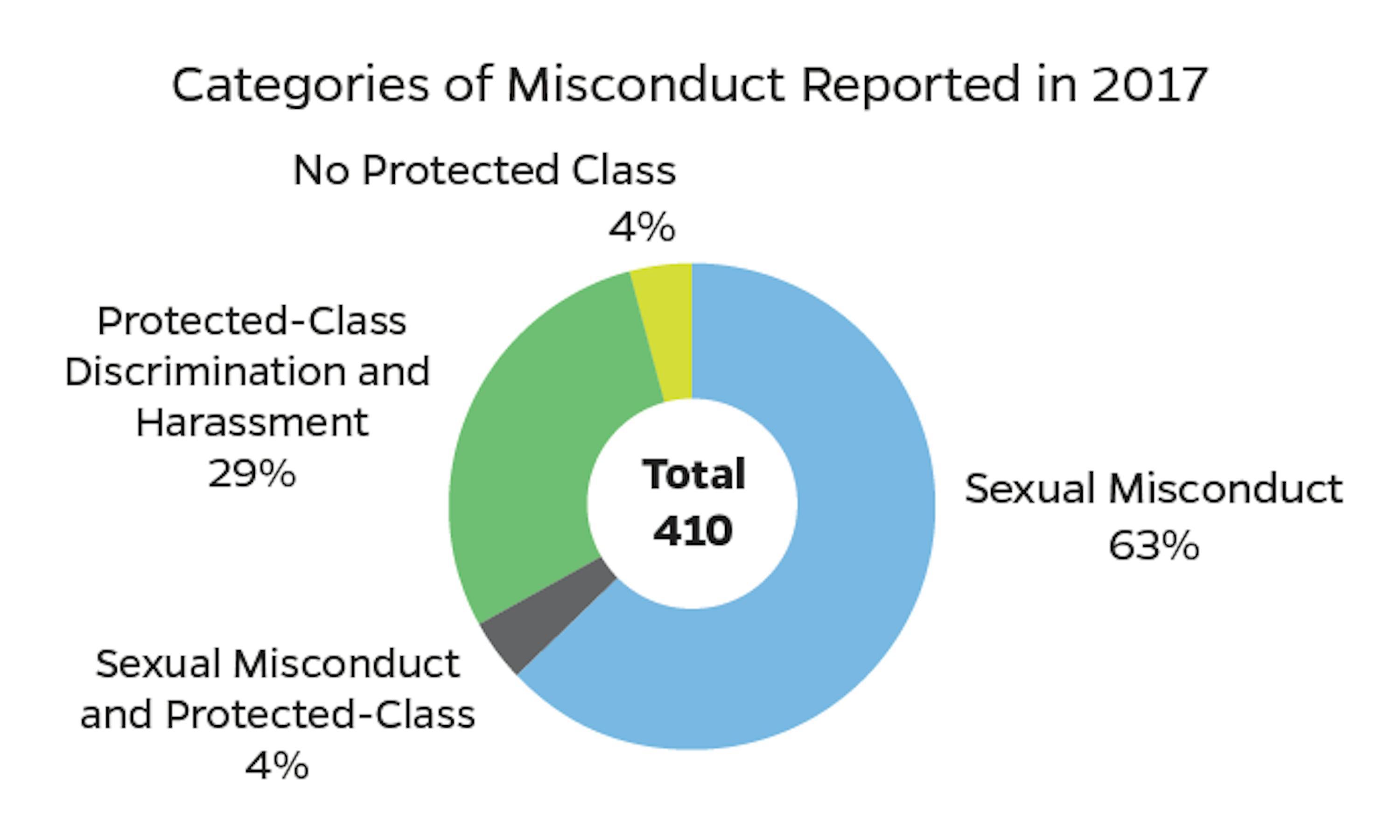

Between 2016 and 2017, the number of reports made to OIE increased by 70 percent, resulting in a total of 410 reports in 2017. While discrimination and harassment reports increased by 53 percent, sexual misconduct reports increased by 80 percent within the past two years.

In a letter to readers at the beginning of the report, Vice Provost for Institutional Equity Kimberly Hewitt explained why OIE decided to create and release the report.

“Our aim in this report is to increase the transparency of our process and our community’s understanding of our work, and provide a baseline against which we can measure our progress in years ahead,” the letter reads.

The report identifies two types of reports made to OIE: sexual misconduct reports and discrimination and harassment reports. Discrimination and harassment cases are further divided into two types: protected class and non-protected class. According to the report, protected-class discrimination and harassment is related to a person’s race, disability, gender, sexual orientation and other similar descriptors.

According to the report, the marked increase in reporting that OIE has seen is consistent with peer universities. The Office’s staff, the report said, has grown from seven in 2015 to 13 in 2017 in response to this trend, with expenditures increasing by 60 percent.

“We believe this growth is driven by a greater awareness of OIE’s work, by university education and outreach efforts, and by the decreasing societal stigma around reporting sexual misconduct or discrimination,” the report reads.

Viswanathan explained that according to data SARU has seen, sexual misconduct itself has not increased. Instead, she said, the number of people who feel more confident about reporting is what contributes to the 80 percent increase in sexual misconduct reports.

“It’s great that reporting has gone up, but this is even more evidence than ever that we need to expand our resources. The survivor population at this school is making itself known and trusting the institution to handle their cases,” she said. “[But] as ongoing issues have shown, we don’t necessarily deliver on those promises at all times.”

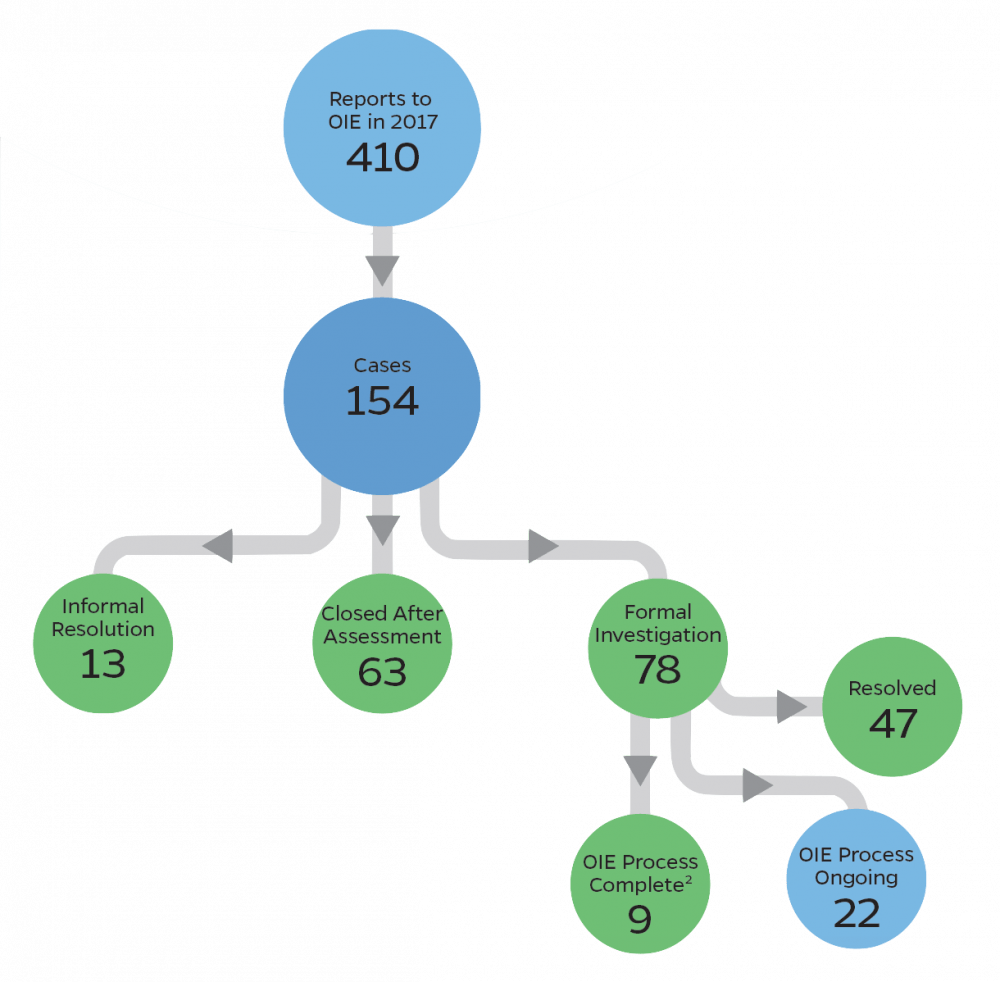

Out of the overall 410 reports made to OIE in 2017, 62 percent did not become active cases. Primary reasons included OIE lacking authority over the respondent or the complainant choosing not to proceed. The “complainant” in OIE’s process refers to the person who reports experiencing a Title IX violation, and the “respondent” refers to the accused perpetrator.

In special cases, however, the Office could proceed with a report against the complainant’s wishes. According to the report, this only takes place “when OIE has a responsibility to take further action.”

Hewitt wrote in an email to The News-Letter that in case of an unknown or unaffiliated respondent, though OIE does not have jurisdiction to pursue an investigation, the Office could take steps to prevent recurrence of the misconduct.

“These steps may include issuing a campus ban prohibiting an individual from entering campus, working with Campus Safety and Security to address campus security concerns, and connecting a complainant with confidential and non-confidential support options at JHU and in the community,” she wrote.

The remaining 154 reports became active cases, with about half of the active cases going to formal investigation. Eight percent proceeded to informal resolution, for which both the complainant and the respondent would have to agree to a resolution.

The OIE report lists 41 percent of the remaining 154 active cases in 2017 as “closed after assessment.” One of the primary reasons cited in the report as to why a case would not proceed to formal investigation was a lack of sufficient information in the report.

Viswanathan called on the University to provide a more detailed breakdown on why 66 percent of sexual misconduct cases were closed without going through a formal investigation.

“That number is concerning, specifically knowing that people only tend to report when they feel like it’s an open-and-shut case,” she said.

Sixty-two percent of protected-class discrimination and harassment cases went through a formal investigation. Of these cases, just 15 percent found a University policy violation.

OIE received a total of 117 protected-class discrimination and harassment reports in 2017, around half of which came from staff. The next largest portion of complainants were students. The 117 respondents consisted of a majority of staff. Faculty, students and non-affiliates each comprised 11 percent of the respondents.

According to Hewitt, staff and faculty have been currently assigned an online module to complete, which aims to prevent protected-class discrimination and harassment.

“OIE is in the process of receiving feedback on the policy and simultaneously socializing and educating members of the University community about it through a series of meetings,” she wrote.

Sanctions placed on protected-class discrimination and harassment report respondents ranged from terminations and negotiated departures to a note of inappropriate conduct to formal reprimands. The report noted that even when OIE does not find in a policy violation, the Office may recommend further action.

According to Viswanathan, it was concerning that 86 percent of closed sexual misconduct cases found that the respondent had not committed a policy violation.

“Knowing the statistics of how many people actually end up reporting out of the total that have experienced sexual violence of some kind, it’s really unlikely that there’s an absence of a policy violation,” she said.

Thirty-four percent of sexual misconduct cases closed in 2017 went through formal investigation. Of these cases, 41 percent found a University policy violation and 59 percent did not.

Viswanathan added that though there are complicating factors like the challenges associated with gathering evidence in sexual violence cases, the process should be made more transparent.

“We need a more transparent view of the elements that make up a ‘verdict’ and a direct correlation between the violation found and the sanctions that are imposed,” Viswanathan said.

OIE received a total of 275 sexual misconduct reports in 2017, a majority of which came from students. The next largest portion of complainants were staff. The 275 respondents consisted of roughly one-third students, non-affiliates and staff, with faculty comprising five percent of the respondents.

Sanctions placed on sexual misconduct report respondents ranged from expulsion or suspension to a note in their formal record to required counseling.

According to the OIE website, the “process to determine whether a violation has occurred and to determine appropriate sanctions and remedies will generally be completed within sixty (60) days from the date of filing the complaint.” Sexual misconduct cases closed in 2017, however, took an average of 264 days.

“Although more than half our cases are closed in four months or less, we recognize the need to streamline the process — including simplifying our reports and adding staff to address concerns about timeliness — while continuing our thorough and deliberate approach,” the report reads.

Reasons that it cites for investigations extending beyond the 60-day target include investigator caseload, the need for a more extensive review of documentation, and complainant or respondent availability.

Viswanathan noted that the 264-day average is a time period longer than an academic year. According to her, this is unacceptable, particularly considering that 264 days being the average means that some investigations were continuing for even longer.

“People are reporting with the idea and with stated policy that it’s going to be closed in 60 days, which is clearly not happening,” Viswanathan said. “We need to communicate off the bat if that’s not going to happen.”

Hewitt stated in her letter at the beginning of the report that OIE has already made significant progress in improving their investigation and report preparation techniques.

“We also hear the call from the community to identify ways to maintain the high quality of our work and complete the process more expeditiously,” she wrote. “In response, OIE has engaged outside support to identify ways to streamline our approach to cases.”

For Viswanathan, the report was a step in the right direction.

“We look forward to continuing to work with them to have productive discussions and improve the process for survivors on campus,” she said.