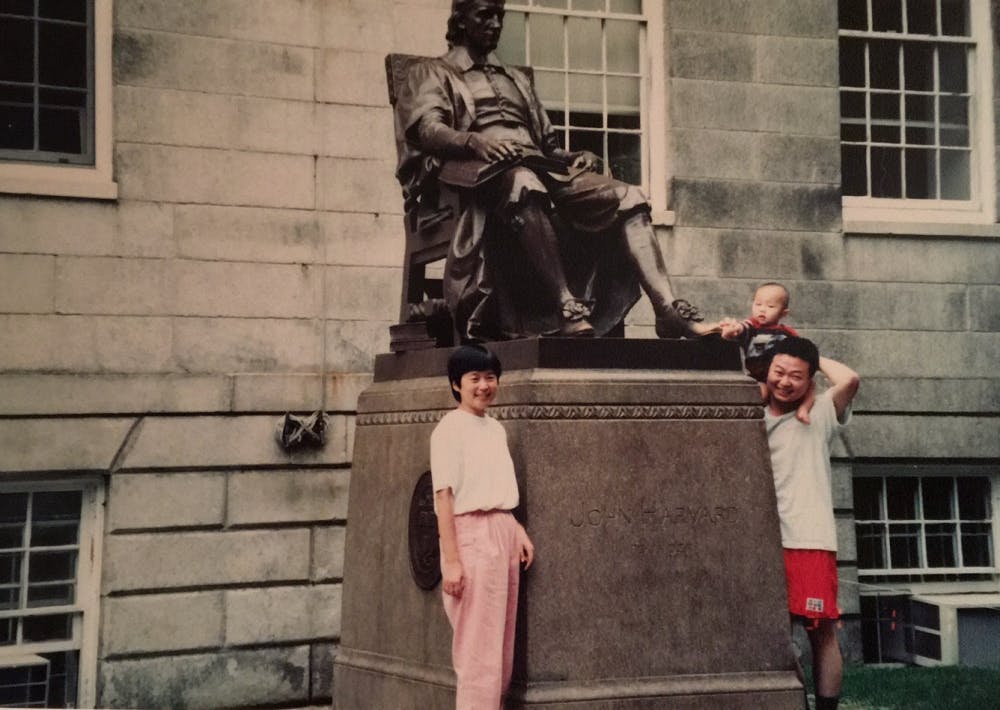

When I was applying to college, my dad told me 山外有山,天外有天 which translates to “there will always be a taller mountain, there is always something higher than the sky.” In other words, there’s always something better out there.

But the one definitive destination beyond the mountains and the sky for many Asian-American parents and their children is Harvard University. Yale can also suffice.

On Monday, a three-week long trial began over whether Harvard discriminates against Asian-American applicants. This lawsuit started in 2014 when the group Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) sued the university for allegedly placing a racial quota on the number of Asian-American students admitted.

Conservative strategist Edward Blum organized SFFA’s lawsuit, and over the past 20 years, he has orchestrated several Supreme Court cases aimed at dismantling civil rights legislation. His 2013 case Shelby County v. Holder led states to roll back voting rights protections. In Fisher v. University of Texas, he found a young white woman to lead a lawsuit against affirmative action. After the Court ruled against him, Blum sought Asian-American plaintiffs instead. Primarily Chinese-American immigrants of the past two decades and their children answered his call.

In this ensuing lawsuit, patterns of racial anxieties intersect with systemic inequalities in higher education. The resulting narratives and perceptions can easily overlook historic and contemporary trends that shape where we are today.

News articles and think-pieces have often implicitly framed Blum as a puppeteer who manipulates unwitting Asian-American props in his conservative master plan to abolish race-conscious policies. This framing hides part of the story. Asian Americans, throughout U.S. history, have consciously aligned themselves with a system of white supremacy with the hope of improving their own status. They did not need Blum’s help.

In the 1927 Supreme Court Case Lum v. Rice, Chinese-American Gong Lum argued that her daughter did not deserve to go to the segregated “colored” school but belonged in the whites-only school. Asian Americans sought white classification consistently in case law like Ozawa v. United States (1922) or United States v. Bhagat Singh (1923). More recently in 2014, Chinese Americans led a successful grassroots campaign to kill a California bill that would have reinstated affirmative action in the state’s school system.

I mention these instances not to erase the history of Asian American solidarity with progressive movements but to complicate the ambiguous place Asian Americans have held in supporting white supremacy. Groups like Asian Americans Advancing Justice have expressed its support for affirmative action, stating that Asian Americans should be in solidarity with other people of color in defending diversity. However, appeals to solidarity and diversity do not resonate for those Asian Americans who see admissions as a zero-sum game.

Over 40,000 students applied for the roughly 1,600 seats in Harvard’s Class of 2022. For the Harvard lawsuit plaintiffs, one student’s acceptance means many others will be rejected. This zero-sum game mindset around admissions reveals a more pernicious problem of inequality and elitism in America’s institutions of higher education. It is not so much that there is a scarcity of seats at “good colleges.” It’s that there is a scarcity of colleges that Asian Americans in particular consider “good.” 山外有山,天外有天.

We shouldn’t blame Asian Americans and America’s aspiring elite for having this perception. Private universities are businesses, and they profit by differentiating themselves to their student customers. As shrewd buyers, we students (and our parents) want to buy the best diplomas our college applications can afford.

For example, elite institutions like Harvard, other Ivy League schools and our very own Johns Hopkins compete in the rat race of college rankings that often evaluate metrics rooted in elitism and inequality, like large alumni donations and low acceptance rates. For President Daniels, being top 10 is literally one of his listed goals for the University. This is the differentiating label where colleges like Hopkins can profit.

In this system of scarcity-driven value, colleges that already have perks attract privilege. Over time, power and resources are concentrated at the top. This process is illustrated by the concentration of legacy students — students whose parents are alumni — at these selective schools. In the Harvard lawsuit, court filings reveal that Harvard places relatives and children of major donors under special consideration.

You can see inequality between colleges through their endowment funds. Harvard’s current endowment is $37.1 billion. Hopkins has close to $3.4 billion. Nearby Loyola University has $192.8 million. Given how these resources differ by orders of magnitude, it’s unsurprising that there is a scarcity of colleges that people consider “good.”

The idolization and concentration of elitism feeds into an admissions dynamic where an overwhelming demand is complemented with a minuscule supply. This demand pushes high school students to pursue extraordinary lengths to be seen by admissions offices. For many, this may mean polishing their resumes with excessive extracurriculars. For the lawsuit plaintiffs, this meant claiming racial discrimination.

Writer Jay Caspian Kang wrote that “Asians are the loneliest Americans.” It’s easy to feel lonely when you feel that there is nothing distinctive about you, which is how I felt in high school. I am a Chinese-American male who focused on STEM and played piano. I wasn’t even good at fitting my stereotype since I knew that my grades were a lower than my Asian friends.

In my senior year of high school, I became more interested in the social sciences. I’d like to think I did that because I enjoyed the subjects, but the nagging thought in my head is “maybe you did it to be different — so you can be seen by a college.”

Findings from the Harvard lawsuit suggest that their admissions officers do have a bit of trouble “seeing” Asian-American students. A statistical analysis conducted on behalf of SFFA by a Duke economist found that Asian-American applicants score lower than other racial groups in “personal ratings,” which include traits like “likeability” and “integrity.” These findings fall into line with typical tropes and stereotypes associated with Asian Americans like their “foreignness” or the saying “All Asians look alike.”

For many supporters of the lawsuit, this is the proof that any racial consideration in admissions is flawed and affirmative action must be dismantled. They live in a zero-sum world, and affirmative action puts them at a disadvantage.

This outlook diverges from what the historical aims of affirmative action have been. Implemented during the Civil Rights Movement, this policy intended to address the pervasive and historic racism that black people faced by mandating that federally-funded organizations provide them with opportunities. However, after the 1978 Regents of the University of California v. Bakke case, the Supreme Court changed affirmative action’s goals in higher education and ruled that race can only be used as one admissions factor among many, with the goal of pursuing a “diverse” class for educational benefits.

Today’s form of affirmative action that is under scrutiny is the product of whitewashing a tool made to address historical injustice. The consequence is that private colleges now pursue “diversity” as a way to market their differentiation to student customers in their race for elitism. Whether affirmative action and “diversity” actually address racism is no longer relevant for universities, as critics of our Hopkins Roadmap on Diversity and Inclusion have pointed out.

The frustrations of these Asian-American plaintiffs and their supporters are disproportionately fixated on race when it should be about unequal elitism in our system of higher education. And as xenophobia and white anxieties grow in the Republican Party, allying with the conservative right will prove to be unsustainable. The Trump administration, which has voiced support for the Asian-American plaintiffs, has also stoked fears that Chinese students are spies from the Chinese government.

At its face value the narrative seems like Asian Americans, under conservative guidance, are attacking affirmative action. 山外有山,天外有天 . There are larger trends at play beyond this story.

This article is abridged in print and the complete version is online.

Rollin Hu is a senior history major from Boxborough, Mass. He was the former Editor-in-Chief of The News-Letter.