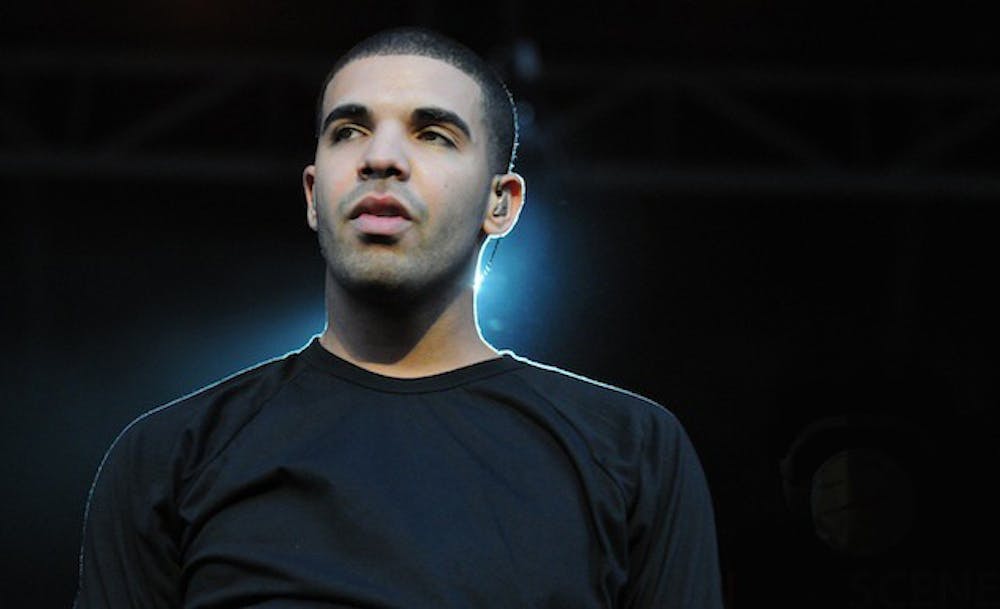

I never thought I would be able to say I’ve danced (and won) the “In My Feelings” challenge in front of Kevin Plank, the CEO of Under Armour. I did not exactly volunteer with the intent to do so, either; in a classic story of overenthusiastic-intern-volunteers-for-literally-everything, I did not even know what I was signing up for before the spotlight was burning a hole through my forehead.

I often feel like a spotlight is about to burn a hole through my forehead. When asked to talk about myself, I tend to play down my accomplishments to seem more relatable to my colleagues and peers. Deep down, I sometimes think that being less intimidating is the key to getting people to like me. Even in job interviews, I fear coming across as arrogant, struggling to quantify my impact and show that I am proud of it.

It would seem that someone with this fear is most likely incapable of dancing a social media challenge in front of 97 other interns, countless employees and a CEO. When people asked me how I possibly could have the courage to do such a crazy thing, I myself didn’t understand at first. It never occurred to me that I could have said no or sat down. Yet in interviews I sit myself and my accomplishments down, often not having the confidence to show off my professional skills. Why is there a difference here?

One is an inconsequential dance that risks social capital more than anything else; the other is a conversation that could decide my entire future. The stakes and the emphasis are inherently and obviously different. However, they both symbolize vulnerable moments where presenting confidence is vital.

This confidence is often elusive, pushed down by a little voice that lists in excruciating detail all of the reasons why the task at hand is impossible. I’m a terrible dancer. Everyone else dancing is better than me. People will laugh and I will never live it down. People will think I’m pretentious. I didn’t get that one position I wanted to in that one organization. I didn’t even join the right organization. My GPA is not a 4.0. They will find someone clearly better. People hate braggers and they are going to hate me no matter what I do.

It is not only tempting to compare ourselves with everyone at Hopkins; it is inevitable. We are surrounded by talented students who continuously face and conquer the world’s problems, making strides in a variety of fields from health and art history to finance and poetry. One of the most important lessons I have ever received was to detach my own success from others’ achievements. My success is not lessened by someone else’s accomplishment. I should not be less sure of myself and my value because someone else did something that I wanted to do, even if they did it better than I could ever hope to.

The reality is that we will always be in the company of people who we perceive as better than us. As long as we continue to exist in high-performance environments, this will always be the case. The sooner we can recognize it, stop putting others down and having unrealistic definitions of success, the sooner we can root for others instead. Then we can begin to view our own accomplishments for what they are rather than how they stack up against our “competition.”

Besides, we all know that friend who “complains” about their impressive research position, competitive internship, twelve leadership roles and their failure to study before an exam they will ace. Humblebragging, the attempt to appear humble while actually listing off your achievements, usually appears thinly failed and dishonest. But when straight-up bragging is unattractive and humblebragging is uncomfortable, what is there to do?

A study by Francesca Gino at Harvard Business School looked at students’ answers to a question about their biggest weaknesses. Over 75% of them humblebragged and tailored the answer to the job description. However, most interviewers were less likely to hire them. Gino wrote, “These findings suggest that in job interviews, showing we are self-aware and working on improving our performance may be a more effective strategy than humblebragging. After all, authentic people who are willing to show vulnerability are likely to be the type of candidates interviewers most want to hire.”

Vulnerability and authenticity promote self awareness, a feat which can be difficult to realize over the course of a lifetime, much less in college. But if we can all examine ourselves as individuals rather than rivals, maybe we can get one step closer to succeeding in an interview and even to letting go of our public dancing fears.