The opening to 2001: A Space Odyssey was a cacophonous blast of sound, drawn out for what felt like minutes against a pitch-black screen.

Just as I was beginning to wonder if a technical error had occurred in the projection booth, the sound began to fade and logos began to cross the screen. Only a few seconds later, the noise — this time the blare of trumpets — returned, now accompanying the camera’s slow pan over the moon.

As we rose past the moon and beheld the entirety of the earth and the sun in perfect alignment, Stanley Kubrick’s name appeared on the center of the screen, accompanied by a massive swell in the film’s score.

In some ways, that was the perfect introduction to the Kubrick 90 film series, an ongoing project by the Maryland Film Festival in honor of what would have been the late director’s 90th birthday. The image of Kubrick’s name overlaid on an image of the entire earth in one of his most infamous films seemed like the perfect way to celebrate his legacy.

Jed Dietz, the founding director of the Maryland Film Festival, explained why the festival decided to host Kubrick’s filmography in an interview with The News-Letter.

“[Kubrick] was, without question, one of the most important artists in the world,” Dietz said. “[The opportunity to see his films] doesn’t come along very often. They’re the kind of movies that are way better to see... in the theater.”

This is a sentiment that echoed my own experience in the Parkway Theatre just a few days earlier.

Watching 2001, I couldn’t help but be taken aback by the spectacle of the whole experience. The soundtrack seemed to alternate between bursting opera and piercing, animalistic screams at a moment’s notice.

Even the scenes that didn’t have a grand soundtrack managed to use ambient noise to heighten the scene’s energy.

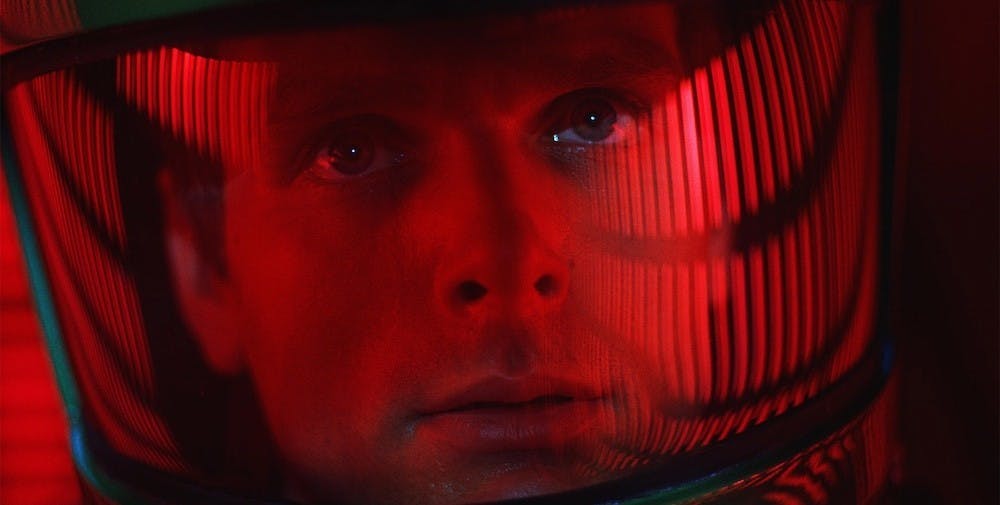

One of the most impactful scenes in the film had no sound other than the slow, heavy breathing of an astronaut that seemed to echo throughout the theater and filled the scene with an intensity that was somehow more moving than any of the orchestral pieces.

All of the film’s visuals were also far more impactful than they likely would have been on a small screen. Several shots featured only a tiny spaceship within the vast void of space, as if to remind us of humanity’s tenuous existence.

From the first act of violence that catalyzes humanity’s evolution to the psychedelic and otherworldly imagery of the finale, Kubrick’s images were almost overwhelming in their sense of scale.

The film series, which is hosted by the Parkway Theatre — where two of Kubrick’s films will be shown every month through the end of this year — is also meant to honor Kubrick’s legacy as a writer, producer and director.

“It isn’t anything technical,” said Dietz when asked about what made the award-winning director so impactful and influential. “[It’s the] artistic ambition in his movies.”

That ambition can clearly be seen throughout 2001, a film that clearly pushes the boundaries of storytelling and redefines what it means to be a film.

Some aspects of the film — like the ambiguous and somewhat minimalist plot or the almost utter lack of dialogue — might turn viewers away; I certainly wasn’t a fan of those traits and walked out of the theater fairly displeased by the film.

However, Kubrick’s aesthetic clearly shines through, and that force makes the movie far more enjoyable for the viewer. The film is filled with long and expansive shots of spaceships slowly moving through the void; as you watch, the small white ships seem to fade away into the darkness, leaving only the nothingness behind.

There wasn’t a voiceover or any daring battles, just a tiny little moment stretching out over the minutes, accompanied only by the orchestra in the soundtrack.

Kubrick forces viewers to confront the vastness and the strangeness in the world around them with the unconventionality of his work. Obviously I cannot judge the entirety of Stanley Kubrick’s work based on a single film; worse, 2001 is the first and only Kubrick film that I have ever seen, which probably makes me even more unqualified to pass some sort of judgment on his career.

However, at the very least, I can say that, as a result of watching the film, I am now much more interested in watching the rest of his work. As Dietz said, opportunities to see these films in the glory and splendor of a movie theater do not come around every day, and I highly encourage you, whether you’re a long-time fan of A Clockwork Orange or a relative newcomer to the cinema scene, to take advantage of everything that the Kubrick 90 series has to offer.