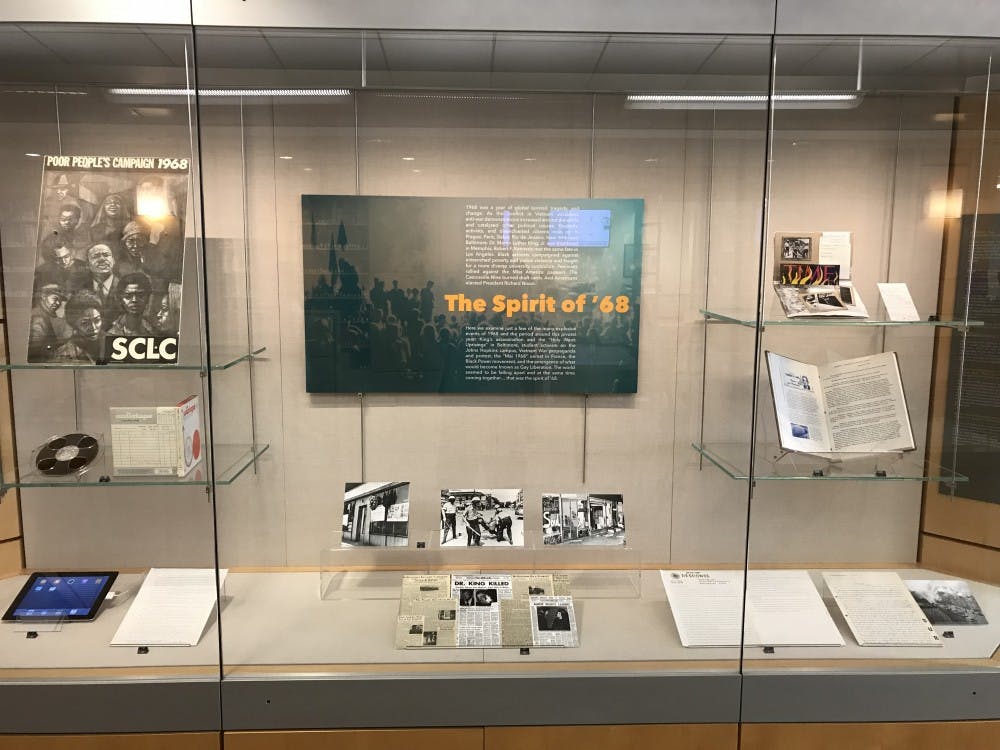

Commemorating the 50th anniversary of the year 1968, curators and archivists at the Sheridan Libraries held an exhibition called the Spirit of ’68. The exhibit displayed photographs, posters, pamphlets, magazines, film footage and archival documents which captured the political, cultural and social unrest of the years surrounding 1968. The event took place in the Milton S. Eisenhower Library (MSE) and lasted from May 29 to Sept 7.

One part of the exhibit focused on the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. (MLK) and the Baltimore Holy Week Uprisings that followed; student activism on the Homewood Campus; Vietnam War propaganda and protest; and the Mai 1968 unrest in France. The other exhibits focused on the Black Power, Black Arts and Gay Liberation movements.

The display focusing on MLK’s assassination included one of his original campaign posters and an audio reel of a talk that MLK gave at the Hopkins campus in 1965. It also included photographs of headlines about MLK’s assassination and the resulting uprising in both The News-Letter and The Afro.

Sophomore Stewart Slocum said that he liked that the exhibit highlighted the University’s response to the events of 1968.

“It’s interesting to see how educational institutions play into the dynamics of certain time periods,” he said.

The exhibit also displayed quotes from African-American students, explaining how it felt to be a student at Hopkins during the early stages of desegregation on campus.

It also included a list of 12 demands made by black students at the time, which included an increase in black undergraduate students and professors, courses on African-American intellectual history and current thought, and having a black barbershop on campus.

Gabrielle Dean, librarian and William Kurrelmeyer curator of rare books and manuscripts, organized the exhibit. According to her, Hopkins was in a predominantly white part of Baltimore, and the lack of a barber who knew how to cut African-American hair was a problem faced by African-American students at the time.

“A black barber shop meant more than just cutting hair. It served as a kind of community meeting hall, a place of getting together and talking about politics, life and other things,” she said.

Dean believes that while some of the demands made by those students have been met, there is still room for improvement by the University.

“We have lots of work on black-American authors; there’re courses on African-American history and thought; there’s certainly African-American staff. However, there could be improvements on all of those things,” she said.

Slocum felt that there was a potential for a skewed viewpoint to be presented in the exhibit.

“These exhibits are a little contrived in the sense that they try to portray the University a certain way and bring a continuity between the University and that time and today,” he said.

The section of the exhibit on the Vietnam War focused on the variety of responses to the war. It included propaganda booklets, publications from South and North Vietnam, and documents both opposing and supporting the war. The display also included photos of sit-ins at Hopkins in response to the war.

Herman Heyn, a Korean War veteran who worked as an office manager in the anti-Vietnam war organization Baltimore Peace Action Center, attended the event. According to him, the exhibit reminded him of protests that he was involved in at the time.

“I was at the Pentagon in October of 1967, outside protesting,” he said. “There were tens of thousands of people. I still have a picture of a soldier using his cigarette lighter to burn down a draft card.”

The rest of the exhibit included artifacts from the 1968 Paris protests against the conservatism of Charles de Gaulle, such as documents on student organizing, fliers circulated at that time and protest art.

It also focused on the Black Panther Party and the Black Power Movement, highlighting the similarities between the demands of the Black Panther Party and the demands of Civil Rights activists, such as the creation of community social programs and better schools. There was also artwork from the Black Arts Movement.

Slocum explained that he would have liked to see more primary source documents from people directly affected by the events of 1968.

“Sometimes these kind of exhibits don’t really capture what was going on at the school in terms of general thoughts, like segregation and the death of Martin Luther King, [it is] a very administrative look at the University perspective on it,” he said. “I think it’d be more interesting to see what students and professors are thinking at large, to read their own primary documents, as opposed to third-party primary documents.”

Dean said that she had difficulty obtaining artifacts from the 1960s.

“People would pick up a flier or poster at the protest, read and keep it for a couple of days, and throw it away,” she said.

She explained that the creation of the exhibit inspired her to look outside of Hopkins for primary source materials.

“The exhibit prompted us to acquire materials that helps illuminate the history, and we’re happy about that,” she said.

The remaining portion of the exhibit covered the Stonewall uprising of 1969, when LGBTQ patrons resisted arrest after police raided Stonewall Bar in New York City. The artifacts on display were from both before and after Stonewall, demonstrating the cultural shift toward acceptance of different sexualities and gender identities after the uprising.

Dean believes that examining primary sources is a great way of understanding history.

“It’s great to read an article or a scholarly book, but when you really read and touch and engage with an artifact from that time, sometimes you just see something no one else has ever seen,” she said.