Since the first successful use of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) as a gene editing tool in 2013, CRISPR has become a large topic of conversation both in science and at the dinner table. Recently, CRISPR has been used to treat Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), the most common fatal genetic disease, in dogs. If it proves successful in humans, it could potentially cure DMD.

CRISPR is a system first found in bacteria as an adaptive immune system. It recognizes pieces of gene sequences of bacteriophages, viruses that kill bacteria, and then integrates those sequences into the bacteria genome. When the bacteria is infected with the same bacteriophage, it can recognize it and activate the specific immune response to fight the bacteriophage.

CRISPR became important for gene editing because it can recognize and replace specific DNA sequences. Theoretically, it can be adapted to recognize DNA sequences that are harmful, such as ones that lead to genetic diseases, snip those out of the genome and replace it with a “good” version of that sequence.

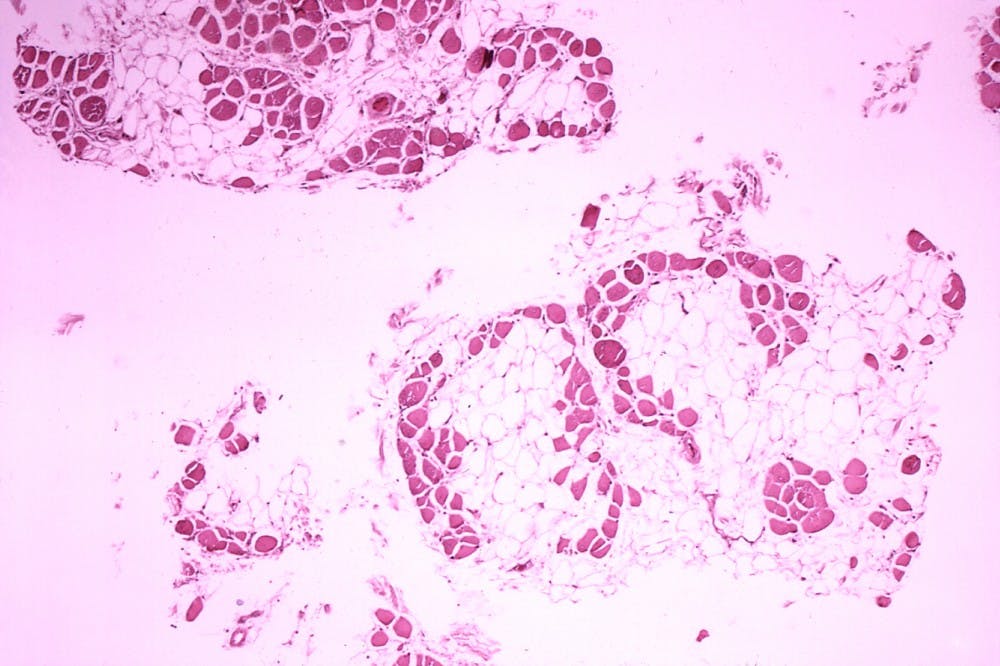

This is what researchers at University of Texas (UT) Southwestern did with the gene that causes DMD. DMD is caused by a lack of a protein called dystrophin, which normally helps muscles stay intact. In patients with DMD, the muscles gradually degenerate and weaken, eventually leading to death.

DMD is one of nine forms of muscular dystrophy, and effects about 15 in 100,000 males per year. The life expectancy is around 30 years.

In a press release, Eric Olson, the director of UT Southwestern’s Hamon Center for Regenerative Science and Medicine explained why DMD is fatal among children.

“Children with DMD often die either because their heart loses the strength to pump, or their diaphragm becomes too weak to breathe,” Olson said.

Currently, there is no effective treatment for DMD, only medicines that delay the inevitable.

In their study published in Science, researchers used CRISPR to edit the gene sequence of four dogs effected with DMD. They used a harmless virus to deliver CRISPR to the cells, which targeted exon 51, a specific location in the dystrophin gene.

Within a few weeks, the muscles showed a large increase of dystrophin, including a 92 percent increase in the heart and a 58 percent increase in the diaphragm. It is estimated that a 15 percent change is needed to significantly help humans with DMD.

Previously, Olson and his team showed that CRISPR can successfully edit the gene mutation in mice and human cells.

“We have more to do before we can use this clinically,” Leonela Amoasii, the lead author on the study, said according to ScienceDaily.

They hope to start human clinical trials in a few years, but in the meantime, the lab is focused on completing long-term studies to see if dystrophin levels remain the same and to be sure there are no adverse side effects of the gene editing.

Although CRISPR has already made a name for itself, research is still being done to better understand it and make it safer for human use.

Anti-CRISPRs are used to make sure cuts are precise and don’t cut out the wrong or excess DNA; previously, only two were known to scientists, but 12 more have been found at the University of California, San Diego.

Scientists at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign have also found CRISPR-SKIP, which, instead of inserting a new gene, actually causes the targeted sequence to be skipped in transcription. This effectively turns off the sequence and prevents the subsequent protein from being made.

Even though CRISPR is a long way from curing humans’ most pervasive diseases, science is constantly coming steps closer to creating a safe and effective system to eradicate genetic diseases.