Kimberly Wong, a junior at Hopkins who is studying cognitive neuroscience, is the first author on a published paper titled, “The Devil’s in the g-tails: Deficient letter-shape knowledge and awareness despite massive visual experience.”

The paper was published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, and has since received press attention from The Atlantic, TIME magazine, ScienceDaily and PsycNet.

Coming into Hopkins, Wong was not sure what she wanted to study. She decided to take a plethora of introductory level classes to see what she might be interested in, including Professor Michael McCloskey’s class, Introduction to Cognitive Neuropsychology.

Wong quickly found herself enthralled by the subject matter and often went to McCloskey’s office hours. At one of those office hours, McCloskey mentioned his lab had openings for undergraduates, and she became a member of the Cognitive Neuroscience Lab.

When asked in an interview with The News-Letter about what cognitive neuroscience is, Wong mentioned specific abilities humans have, such as picking up a pencil with their fingers in the right grip or remembering how to get home.

“Cognitive science breaks down these mechanisms, deciphering where these processes happen in the brain, as well as how the brain carries out these processes,” she said.

McCloskey’s Cognitive Neuroscience Lab focuses on three projects, one involving reading and writing, another on spatial orientation and a third on case studies on patients with neural deficiencies.

During a lab meeting, the group was discussing allographs, the different shapes and forms that letters can take. McCloskey brought up the fish-tailed and loop-tailed forms of the letter “g.”

“He was surprised to find that basically no one besides him knew what he was talking about,” Wong said.

The fish-tailed loop “g” is the lower-case “g” we learned how to write in school, with a circle on top and an umbrella hook on the bottom. This is what most people think of when they think “g.” The loop-tailed “g” is the most common in print, with a loop on top and a closed loop on the bottom. It is used in common type-fonts such as Times New Roman, Calibri and this newspaper’s font, Palatino.

It turns out that the lab members were not the only ones to not realize “g”s took two forms. That conversation spurred studies into the general knowledge of what a “g” looks like.

The first study was based on the general question, “Can you list letters that you think have two forms in lowercase print?” and if participants didn’t mention “g,” they were prompted with further questions, ending with the researchers saying, “The letter ‘g’ has two forms — can you write them?”

Thirty out of 38 participants got to that last question, and 12 attempted the loop-tailed “g” with varying success. The second study asked new participants to read a paragraph silently but read words including a “g” aloud.

After they were asked to reproduce the “g” they just saw. Half drew the fish-hook “g,” and of the half that were aware of the loop-tailed “g,” only one could draw it correctly.

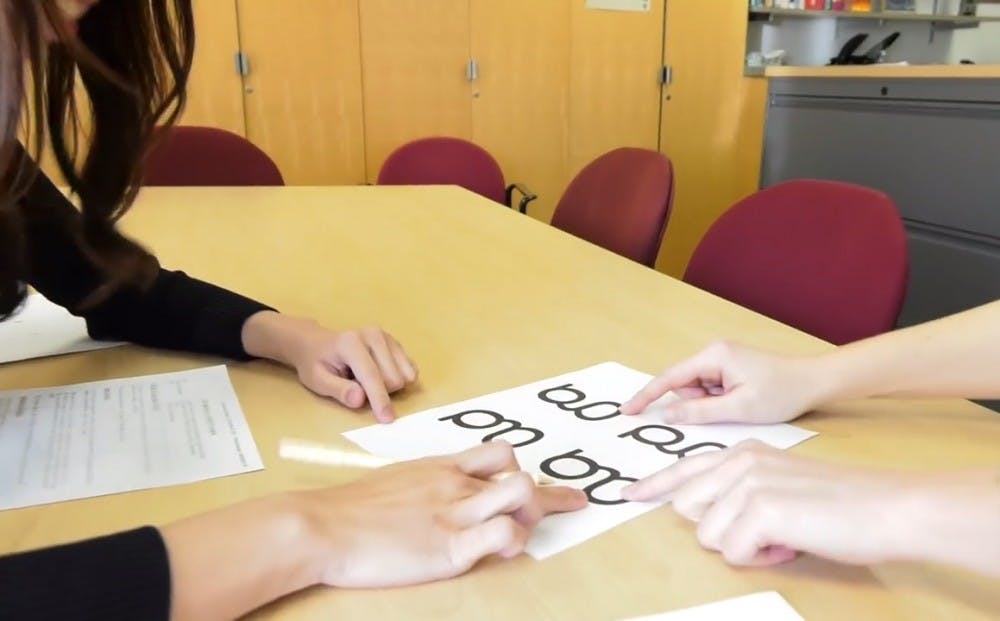

The third study involved showing another set of participants four different variations of the loop-tailed “g” with only one correct version, and they were asked to choose the right one.

Wong expressed her surprise regarding the results of the test.

“We definitely walked into that experiment expecting everyone to select the correct loop-tail ‘g’ out of the four ‘g’s presented,” she said. However, 18 out of 25 participants chose the wrong “g.”

The lab found these results surprising; after being exposed to the loop-tailed “g” all our lives, it is logical to assume we can recognize it.

But these results prove differently: We learn what the loop-tailed “g” looks like, but only the important parts that are necessary for quick recognition.

Wong says these results have larger implications.

“We’re really looking into more than a letter here. It’s about memory — what is needed to store complete and accurate pieces of knowledge,” she said.

Starting in the Cognitive Neuroscience Lab, Wong had no illusions of publishing a paper that cited her as the first author.

Wong says she initially had no experience, but McCloskey and Gali Ellenblum, a graduate student in the Cognitive Neuroscience Lab, mentored her and eased her in to the skills and methods needed in the lab.

In the summer of 2017, Wong worked in the lab with the aid of the Summer Training and Research (STAR) program.

Wong cites this as the reason she was able to achieve first author: Over the summer she was able to devote her time to the project, and with all the work she put in, McCloskey and Ellenblum decided she should be first author.

Wong also stressed that this paper would not have been published without the help of McCloskey and Ellenblum.

“The paper wouldn’t have become what it is without the many drafts they edited and fixed,” Wong said.

When asked how she felt about such immense interest in her research, Wong expressed her disbelief.

“I couldn’t really wrap my mind around it all — I still don’t think the excitement in me has died yet!” she said.