I’ll start with a disclaimer: This article is going to discuss my experience with the Bystander Intervention Training (BIT) program during my freshman year. The program may have changed or evolved since my experience. I’m not criticizing the way it works today, but what happened during my BIT session was not okay.

Hear me out.

I am a victim of childhood sexual assault. So I tried to delay BIT as much as I possibly could. With the threat of not being able to register for classes my sophomore year looming, I grudgingly signed up for a BIT session. You might ask: Why did I do it? I could have emailed them and said I wasn’t feeling up to it, right?

I just wasn’t ready during freshman year to acknowledge in an email to a stranger that something had happened to me in the past that warranted me being able to miss my BIT session.

So I went. After all, it was a program designed to fight the culture that furthered sexual misconduct on college campuses, so it couldn’t hurt me that much, could it?

At the beginning of each session, they said that if you for any reason need to step out, you can, and that’s okay. But listening to that I knew that no matter how bad it got, no matter how much something was affecting me, knowing myself there was no way I’d have the courage to get up and leave the room.

Just thinking about the possibility of leaving the room I could almost feel the ghost of 20 pairs of eyes on me, following me as I walked out the door. I could feel the pain of knowing that 20 people would know that something had happened to me. And I was terrified of making myself vulnerable like that.

So I decided to tough it out.

At some point during the second session, they handed out a piece of paper to each of us that we were supposed to tear into four pieces.

For the first piece, we were supposed to write down an activity we loved doing, that we couldn’t live without, that gave us joy. I just wrote “reading.”

For the second, we were supposed to write down a place where we felt absolutely and completely safe.

And I froze.

With my pen hovering over the paper, I struggled with myself to keep the tears from falling. You see, it happened at my home. I looked around, saw that most people were writing “my house” or “home,” and I tried to just copy them and do the same thing, but my hand was too shaky.

He had been to my home multiple times a week for five years. He had been in my bedroom. I couldn’t even lie and write down “home.”

So I left it blank, all the while paranoid that someone would turn their head and see that I couldn’t bring myself to write anything on that second piece of paper.

Third: Write down the name of the person in the world you trust more than anyone else; someone you could tell anything to. I wrote the name of the first person I ever told about what had happened: my friend who had held my hand and told me it wasn’t my fault and convinced me to talk to my therapist about it.

Fourth: Write down your deepest darkest secret that you wouldn’t want anyone else to know. I couldn’t even bring myself to picture what had happened in my head, let alone write it on a piece of paper.

I had left two of the four pieces of paper blank, and I was sitting there hoping with everything I had that no one would notice, and I still didn’t know what this activity was leading up to.

They told us to crumple up the first piece of paper. They said that once you go through something like this, even the activities you love doing lose their meaning.

They told us to crumple up the second piece of paper. They said that once you go through something like this, you stop feeling safe, sometimes even in your own home — like I didn’t already know that. So I crumpled up a blank piece of paper.

We crumpled the third. They said that experiences like this can damage your relationship with your friends, your parents, your partner, the people you love and trust most. So I crumpled up the name of the first person I had ever trusted with my story.

And then we didn’t crumple the fourth. I was waiting for that. I was waiting to crumple up the piece of paper that was supposed to contain that secret, and we didn’t. They said that when something like that happens to you, sometimes that experience, that secret, is all that’s left.

They said that we could un-crumple the rest of the pieces of paper, but they’d never be the same. They said if something like that happened to someone, they’d never be the same. They’d always be marked by it. There would always be a hole.

The thing is, I understand where they were coming from. They were looking at BIT as a preventative measure. They thought maybe they could discourage someone in the room who was a potential perpetrator. They thought they could encourage someone in the room to intervene if they saw something.

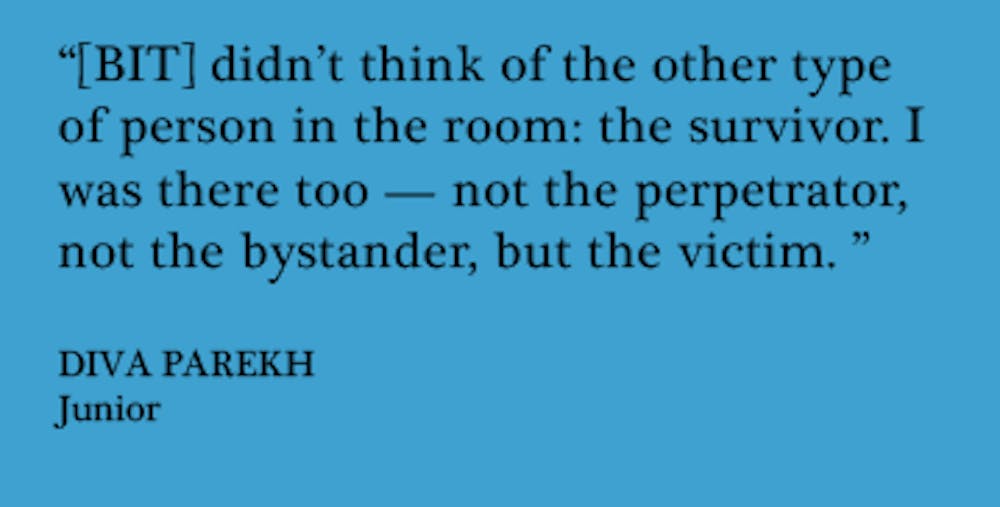

But they didn’t think of the other type of person in the room: the survivor. I was there too — not the perpetrator, not the bystander, but the victim. And they said it themselves: One in four girls and one in six boys will be sexually abused before they turn 18 years old.

Why didn’t they consider that in a room of over 20 people, at least one of them might fall into that third category? In their fight to stop sexual violence from happening at Hopkins, why didn’t they care that it had already happened to me a decade before I ever set foot on this campus?

When I got home, I was lying in my bed as I told my roommate about it. She went to my backpack, took those pieces of paper out, threw them in the trash and then took out the trash.

But I still think about them. I still think about that second piece of paper I left blank because I don’t know if there’s a place where I can feel perfectly safe. I hear the words “there will always be a hole.” There will always be a void. Every single time I fight those memories, I fight those nightmares, and I fight to go to sleep, I hear those words and I’m terrified that I’m fighting a losing battle.

Again, things may have changed. BIT may not work this way today. But I wish it hadn’t worked that way with me.

Diva Parekh is a junior Physics major from Mumbai, India. She is the Copy Editor of The News-Letter.