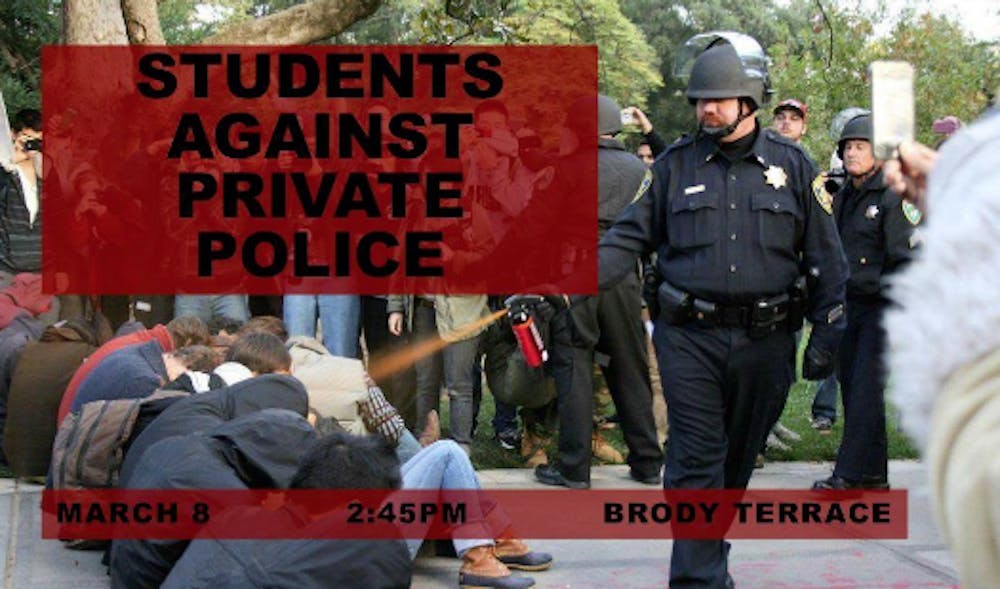

A protest on campus hosted by Students Against Private Police advertised with a now-famous picture of the University of California (UC), Davis police pepper-spraying peaceful protestors. In her book Campus Sex, Campus Security, Jennifer Doyle writes about the above incident of brutality. As she explains, the UC Chancellor said, “We were worried about non-affiliates... we were worried about having very young [university] girls and other students with older people who come from the outside.” The Chancellor feared black men from Oakland coming on campus and assaulting the University’s women. The fear of sexual assault comes from a racist national mythology of the black male rapist — not feminism. The University sees women as liabilities, not autonomous beings. Sexual assault is mostly student-on-student and vastly under-reported by both victims and the University in crime statistics. Crime data is skewed towards robbery and theft — misrepresenting those from the “outside.”

Hopkins President Ronald Daniels echoed the UC Chancellor in his email about forming a Hopkins police force. Police are necessary, according to President Daniels, “given the challenges of urban crime here in Baltimore and the threat of active shooters in educational and health care settings.” He signals, as the UC Chancellor did, that the police are meant to put a wall between black residents (urban crime) and students. Affiliates in the learning fortress don’t commit crimes, right President Daniels?

He evokes the Parkland high school shooting in arguing for the private police — despite the fact that Parkland occurred even with armed guards in place. Research has shown that a police presence leads to an escalation of issues, rather than a reconciliation. If President Daniels wants to reduce the likelihood of a shooting, it’s largely not advised to introduce a squadron of weaponry to the campus. We must ask ourselves, and the school, if private police will impact this crime.

Quinn Lester, a Hopkins graduate student studying policing, said in an interview that “there is little scholarly consensus that more police equals an increase in safety. Just looking at Baltimore City, the BPD have a notoriously low clearance rate, and there is little reason to believe a Hopkins police force would be different.”

Not only are private police ineffective, they are injurious. A neighboring college, Morgan State University, has a police force that participated in the beating and murder of Baltimore resident Tyrone West. He was a non-affiliate, killed by private forces one mile from Morgan, that were not accountable to him. Another model department for the Hopkins police force, the University of Chicago, has been criticized for its racial profiling. An article in the Chicago Reporter says, “African-Americans make up approximately 59 percent of the population in UCPD’s [University of Chicago Police Department] patrol area but 93 percent of UCPD’s investigatory stops.” Black residents of the neighborhood near campus are stopped so often, the officers know the residents’ names. University police disproportionately stop, harass and even kill black residents in their own neighborhoods.

But, being university police forces, the departments are not bound by the Freedom of Information Act. As Lester said, “there would be little recourse at all for learning about what exactly a Hopkins police force would be doing to whom.” The police forces aren’t obligated to disclose data. Further, whereas residents vote for city council members who control city police leadership, neighboring residents would not have any voice in the introduction of an armed Hopkins force. They would have no participatory voice in the Hopkins patrol and would feel a larger wedge between their community and Hopkins.

In her book, Doyle also tells the story of UC Los Angeles student Mostafa Tabatabainejad who was tasered while at the library after refusing to produce government ID (which was not required in order to be there). The stories of brutality go on and on. President Daniels tells us they are “establishing a university police department, specifically trained to meet the unique needs of a university environment.” What about a university environment necessitates my black and brown peers be tasered, my neighbors detained?

Small infractions become moments of brutality; the library becomes a site for assault. A woman is a body waiting to be trespassed — or better yet, a redacted name in a file, a corpus of liability. Black students are not students but possible non-affiliates, possibly suspects. We are customers going into debt while the University finds funds for police. Why do we need armed guards in watch-towers around our learning fortress in order to read Milton next to paintings of slave-owners?

As Doyle said, “The walls dreamed up by University administrators and their consultants had the aspect of the madness that was the engine of the problem.”

Private police forces are an attempt to solve robbery, sexual assault and gun violence, using the logic of those crimes. We need a radical love for the impoverished, women, trans folk and Black Baltimoreans — not another wedge.

Stephanie Saxton is a senior Political Science and English major from Clarksburg, N.J.