Staring up at the heavens is something all humans, whether a thousand years ago or today, have done. Bloomberg Distinguished Professor Charles Bennett, an experimental cosmologist and recent recipient of the Breakthrough Prize, looks at space with the same fascination, harnessing the power of science and engineering to understand the universe’s deepest secrets.

At a very young age, Bennett was set on studying cosmology.

“On one morning before school, I was a reading a book called From Flat Earth to Quasar by Isaac Asimov, and it said that a couple of scientists think that they’ve discovered microwaves coming all the way from across the universe from the Big Bang,” Bennett said, “My jaw dropped... I just thought that was the coolest thing in the world.”

Bennett said that he realized then that cosmology was perfect for him, combining his two interests of electronics and astronomy.

“I decided right then and there — that’s what I was going to do,” Bennett said.

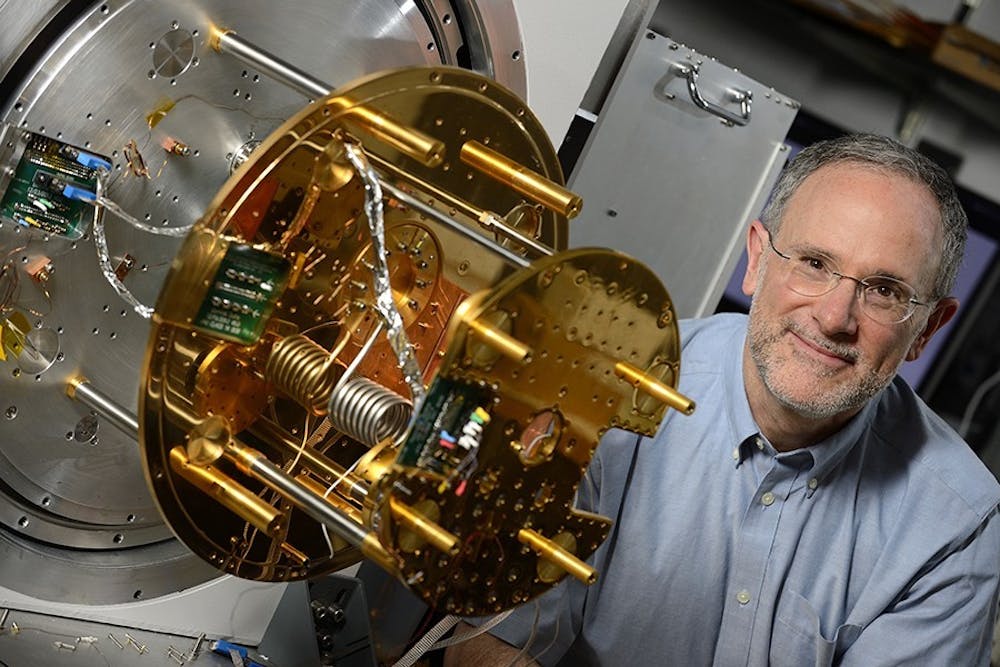

From 2001 to 2010, he led the NASA Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP), which analyzed the fluctuations of the cosmic microwave background (CMB). These microwaves are left over from the very beginning of the universe, an extremely high-energy event. This left a distinct pattern of microwave radiation, which WMAP aimed to analyze to better understand the process of the how the universe began.

WMAP lead to important findings, including that the universe is made up of five percent atoms, 25 percent dark matter. The remaining 70 percent consists of a cosmological constant, also known as “antigravity.” Bennett emphasized the importance of this revelation, explaining that it means the atoms we can actually see are only five percent of the universe.

WMAP also disproved common theories about the beginnings of the universe.

“This early time, the best idea we have so far is called inflation. We tested different, specific models of inflation, and the two most popular models which were actually taught in textbooks — we actually ruled those out,” Bennett said.

For his work with WMAP, Bennett was recently named the recipient of the Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics, a highly prestigious award in the academic community. The entire WMAP mission science team will share the $3 million prize.

“It’s great to be honored by your colleagues, and for them to say ‘Hey, that was great work!’ [But] when you’re doing these things, you don’t think of it that way,” Bennett said. “When I spend 32 hours in a meeting about whether a bolt should look like this or like that, I’m not really thinking about those things.”

Now at Hopkins, Bennett still does work with the WMAP data. Recently, there has been tension in the cosmology community between data sets, and he is working to smooth out the kinks.

Bennett is also working on the Cosmology Large Angular Scale Surveyor (CLASS) project, which also studies CMB but focuses primarily on the polarization of the light. Bennett noted that CLASS has a wide range of expertise working on the project, including several undergraduates.

Bennett cites undergraduates as a big reason for why he is glad to be back on a college campus.

“I never fully appreciated how great it is to have students around; having students come through, coming in naïve about the science and leaving as experts... that’s a lot of fun,” he said.

Bennett also works to bring a lot of the various research projects being done on campus together and make them accessible to anyone. He is the director of Space@Hopkins, which links different programs on campus, from Earth sciences to robotics, that are interested in space-related research.

Bennett also described a meeting he put together last year, where various Hopkins scientists were allowed to present their research, giving researchers across campus an opportunity to gain a better understanding of who was on campus and what they were doing.

Bennett emphasized that science today has grown into an extremely collaborative field. Bennett also said that Space@Hopkins has the ability to match students looking for research positions with professors who are looking for undergraduates, acting as a “matchmaker.”

Over the years, Bennett’s fascination with cosmology and the sciences has not wavered, and it inspires him to keep looking for answers.

“I will always think about those big questions and wonder: Is there a loose thread somewhere I can pull on and make this stuff unravel?” Bennet said.