For years, Baltimore City Public Schools has faced unprecedented debt, overcrowded classrooms and faculty cuts that result in limited opportunities for students to explore the arts.

As city officials work to address these issues, the nonprofit Writers in Baltimore Schools (WBS) aims to expand students’ creative writing and literacy skills within a school system currently struggling to provide those resources. Since its inception, WBS has worked with over 600 students.

How WBS works

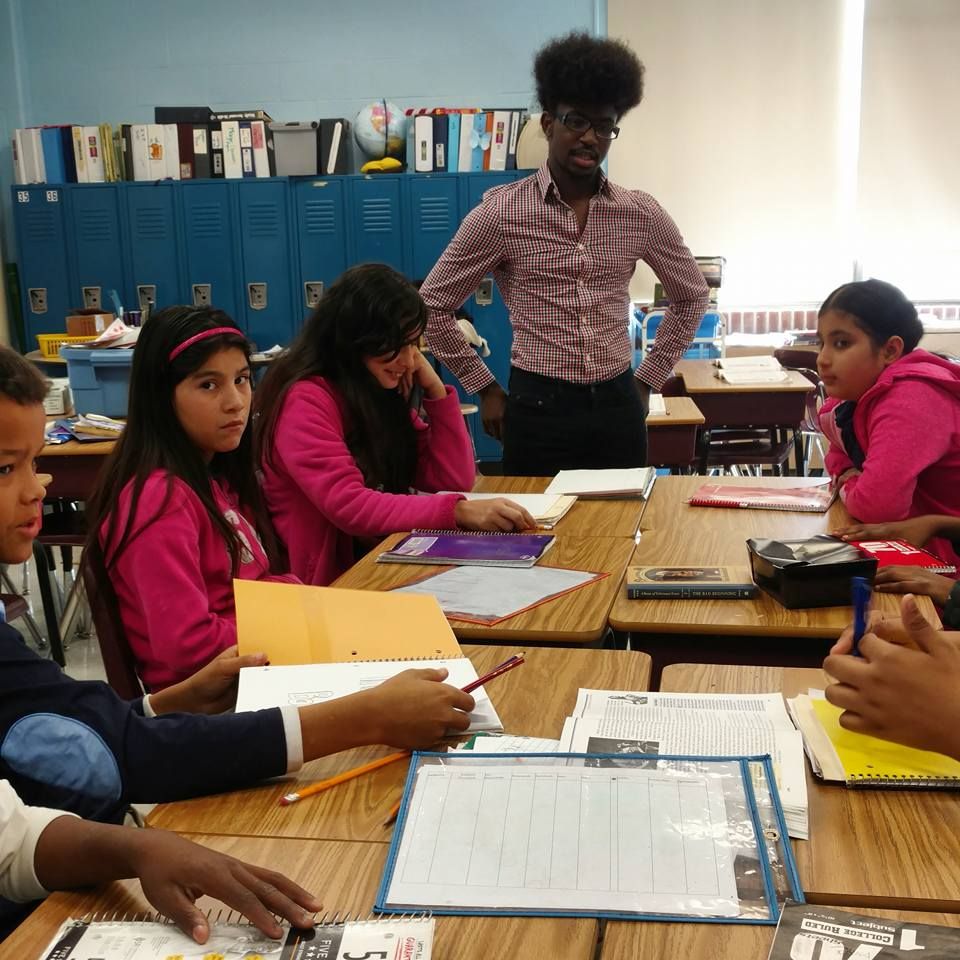

WBS has a program advisory board which counsels instructors and teaching fellows who work in Baltimore City Public Schools to develop curricula that will engage Baltimore’s students in the creative arts.

WBS draws its instructors from the Writing Seminars department, the University of Baltimore Master of Fine Arts (MFA) program and Morgan State University.

Hopkins undergraduates can work with WBS by taking the course “Fiction and Social Engagement,” which will be offered this spring, or by volunteering at Baltimore schools on a weekly basis and leading workshops.

Last year, eight Hopkins students worked in schools as a part of WBS. Stephanie Haenn, a junior Writing Seminars major, has been volunteering with the program for the past year. She enjoys working in classrooms and appreciates that volunteering with WBS allows her to get off campus.

“I really just wanted to get out of the Hopkins bubble in a way that wasn’t just going to the Inner Harbor or Hampden, so that’s why I originally joined,” Haenn said. “There was one girl who would hug me every time I came in, which made me really happy.”

According to Haenn, around a quarter of students in the classroom where she volunteered were interested in writing and were able to delve into a creative outlet different from what is normally offered in school.

“The poems and stuff that they create are shocking, that they are coming from a sixth grader,” she said.

In addition, Haenn said that teachers are often required to stick to a strict curriculum.

“I know the teacher that I specifically worked with, she really focused on bringing in outside people to provide creative things,” she said. “[The kids] definitely expressed different creativity than they would in their normal language arts [curriculum].”

Undergraduates have created lesson plans that include poem and story prompts that allow the kids to write anything they want.

For instructors, the lessons they teach middle schoolers through WBS can mirror their instruction with older students in other classrooms.

Jessica Hudgins, who earned an MFA in Writing Seminars, has taught at both WBS and Hopkins. She used the same two poems — Langston Hughes’ “The Dream Keeper” and Emily Dickinson’s “To Fill a Gap” — in both her WBS class and her class of Writing Seminars undergraduates.

“We were able to talk in both spaces about the same thing, but in different ways depending on the age difference,” she said. “It was a cool experiment to see what I had to do in order to have the same conversation about what the poems mean with both groups.”

WBS was created by Patrice Hutton, a Hopkins Writing Seminars alumna, in 2008 with the help of a community fellowship grant.

Hutton originally focused the program on middle school writers but said WBS has evolved over time to include writers of all grade levels. She said that the organization tries to form long-term connections with its students.

“Even in college, we’ll bring some of [our students] back to work as teaching assistants or instructors,” she said. “One student who was with us from the very beginning, our first seventh grade group at Margaret Brent [Elementary/Middle School], is now our activities director at camp.”

This year, in-school programs are offered at Margaret Brent Elementary/Middle School, Calverton Elementary/Middle School and Barclay Elementary/Middle School.

Students in the WBS Summer Studio program, an immersive writing retreat, collaborated with The Baltimore City Paper to create a view of the city through profiles, poetry and prose that was published in September. Marc Steiner, a local radio host, and Lester Spence, an associate professor of Africana Studies at Hopkins, were among the people profiled.

Hutton said that programs like WBS are necessary now more than ever because the introduction of standardized education into Baltimore’s public schools has decreased the amount of space available for students to express their creativity.

However, this is not the only problem plaguing Baltimore’s public schools.

A school system in debt

Students in the Baltimore public school system are affected by debt that cuts into the opportunities provided in the classroom.

According to The Baltimore Sun, the City’s school system is currently $130 million in debt. School enrollments are also decreasing, which exacerbates the problem as Maryland’s state system awards more money to schools with higher numbers of students.

School enrollment has fallen during three of the last four years, and the trend is expected to continue, so city officials are working to get parents to enroll their children in public schools to better distribute funds.

According to The Sun, state and city officials also pledged $180 million over the next three years to offset some of the current debt that is attributed to the decreasing enrollment as well as higher teacher salaries and a school construction program.

However, other problems still persist. Some schools are understaffed, even with decreasing student numbers. According to The Sun, 115 people were laid off at Baltimore public schools in June. This is the third straight year of layoffs in the district.

In addition, large class sizes can make it difficult for students to receive individual attention.

Hutton reports knowing teachers who have 38 students to oversee in a single classroom; one of the classrooms Haenn worked in had more than 30 sixth graders. Some Baltimore educators fear that increasing class sizes will make it impossible to serve their students well.

School staff was also cut by nine percent between 2015 and 2018. Many believe that underfunding, as well as fewer faculty, makes individualized attention for students a rarity, if not impossible.

Despite these challenges, WBS says they aim to help provide students with the creative outlets that they might miss out on in the classroom.

While higher test scores have not necessarily been recorded from WBS participants, students have had pieces published in outlets like The Poetry Foundation’s blog, The Washington Post and The Baltimore Sun.

Additionally, instructors and student volunteers say that kids love getting to experience creativity that is different than their usual classroom activities. The program’s first class of students has now graduated from high school, and some of them have continued to practice the creative arts in college.

Baltimore is far from being the only city in debt. Public school systems are underfunded across the nation.

According to U.S. News & World Report, poor pensioning is the underlying cause behind debt many systems face. The Sun defines poor pensioning as “a gap between the funds in the [city’s] pension account and the amount owed to retirees.”

On the student-teacher level, many cities have programs similar to Writers in Baltimore Schools.

The InsideOut (iO) program in Detroit has a long history of creativity. It has worked with over 50,000 students to help them find their voices since its founding in 1995. Kids and parents can also take advantage of 826michigan, which offers a notable after-school creative writing program.

Baltimore itself is also home to organizations like: 901 Arts, a youth arts center; Baltimore Youth Arts, an arts entrepreneurship and job readiness program; and Wide Angle Youth Media, which promotes media arts education. These organizations work to provide young people with opportunities to explore their creative interests outside of the classroom.

Some think that the answer to Baltimore’s public school system debt is increasing enrollment, but Hutton wrote in an email to The News-Letter that schools need more than higher numbers.

She argues that they need racially equitable funding. Paula Dressel of the Race Matters Institute defines racially equitable funding as the idea that it is “critical to invest in ways that erase those gaps that for too long have compromised the promise of children, families, and communities of color.”

Dora Malech, a member of the WBS advisory board and an assistant professor in the Writing Seminars department, said that problems students face in Baltimore schools do not stem from the classroom itself, but they do impact how children perform and express themselves.

Baltimore’s transportation infrastructure, for example, makes it difficult for students to travel to after-school activities.

“To have creative opportunities in the classroom or in these summer programs are really, really crucial,” Malech said. “Feeling like you have a creative community, feeling like you’re able to use your voice and you have this creative outlet and you’re building your academic skills and your literary skills at the same time is really valuable.”

A look into the future

WBS is currently in its third year of partnering with Hopkins. High school students travel to Hopkins for classes, while undergraduates visit elementary and middle school students in their classrooms.

Rachael Barillari, a seventh and eighth grade teacher at Margaret Brent Elementary School, said that collaborating with WBS has been beneficial for her students.

The theme of her classroom is “We are college bound,” a slogan that especially permeates her students’ creative work with Hopkins students.

“We talk a lot about college readiness,” she said. “The biggest benefit is that middle school kids [get to] see actual college students come into their classroom, talk about what they do at college and work with them on their writing.”

Barillari took her sixth graders on a tour of the Hopkins campus last year, where they ran into a student who had been volunteering in her classroom.

“The writers we work with at Hopkins have definitely been a huge asset for working with middle school kids. It helps [college readiness] to have people at Hopkins as the students’ mentors in the organization,” Barillari said. “It has been a wonderful collaboration.”

As a non-profit organization, WBS relies on donations, foundation support and fundraising efforts in order to fund its efforts. Its future depends on ensuring that funding will continue to support various programs.

Malech explained that it is hard to measure the impact that creative programs have on students, which can make the task of convincing potential donors to contribute money difficult.

“We have this anecdotal evidence, but I do think it’s always a challenge in terms of funding to be able to quantify that,” Malech said. “That’s something we can really build on in the future and we’ve talked about a lot as a board.”

She said that because of these challenges, WBS needs to be creative in how it fundraises.

“How do we show to funders, to the outside world, even at Hopkins, a place that’s very data based — how do we show the impact that we see and that the students themselves see in a very real way — how do we quantify that?” she said.

Malech added that it is difficult to be dependent on year-by-year fundraising without a permanent endowment, as is the case for many local grassroots organizations in Baltimore.

“That’s an area where I think Hopkins students could get more involved: in terms of thinking of creative ways to fund the organization and to draw attention to the organization to keep it sustainable,” she said.

In terms of future programming, Hutton said WBS is looking to involve itself more with local media outlets, an initiative spurred by WBS’ summer collaboration with The City Paper.

“Two of their editors came out to our summer camp and did two days of workshops with kids, and we actually collaborated to publish a fully student-written issue of The City Paper,” she said. “So I’d say there are things like that kind of on the horizon in Baltimore. We really want to work with different platforms to get student voices out there.”

There are also individual projects in the program’s future, but Malech says that no matter how WBS expands, the emphasis should always be on the students.

“[The program] could grow indefinitely into more and more schools, but I think it would take more funding to do that, and I’ve seen nonprofits spread themselves very thin,” Malech said. “It makes a lot of sense, and it’s healthy for the organization to focus on really connecting with each individual student rather than trying to only aim for numbers.”