If you were to ask a random person to outline our generation’s defining characteristics, you would probably hear a string of descriptors fitting something along the lines of “entitled,” “lazy,” “technologically driven,” perhaps “misunderstood” or “thoroughly cheated.”

Depending on whom you ask, all of these are valid adjectives. However if someone were to ask me, what would come to mind as a defining feature is our bizarre (bordering nonsensical) sense of humor — our meme culture.

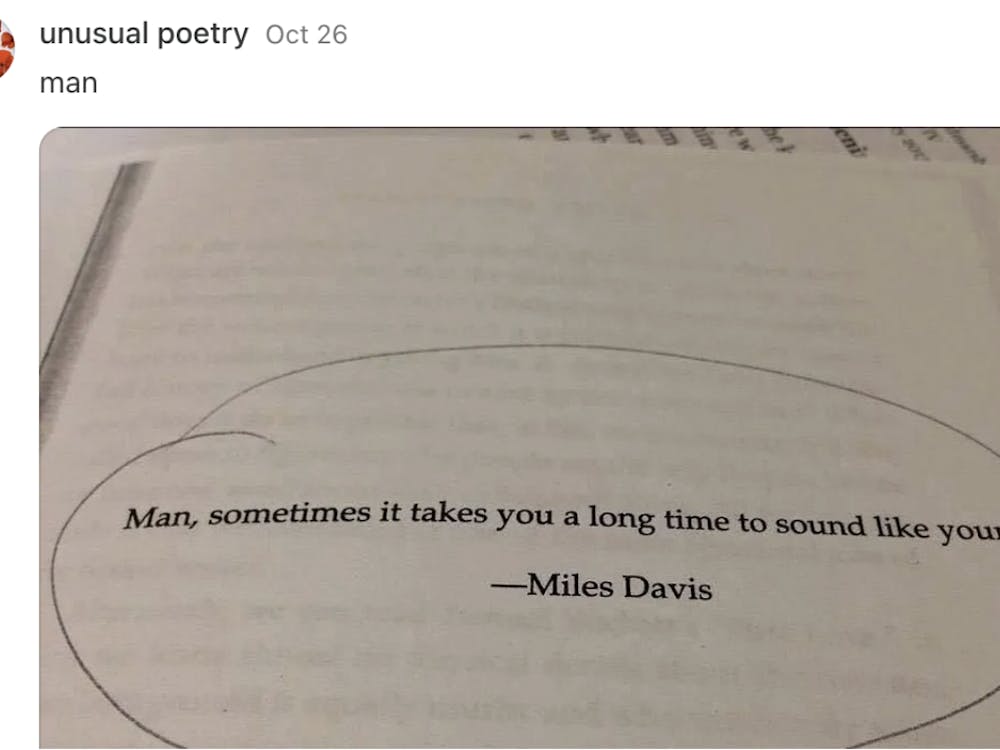

Twitter, Tumblr, Buzzfeed and even our own University meme page all serve as perfect examples of this generational peculiarity, boasting post after post of jokes so niche that even students fluent in dank memes sometimes can’t understand them, let alone people from other generations.

Beyond their inherent bizarreness though, what is particularly noteworthy is that most of the jokes our generation makes seem to be centered on death and suicide.

Jokes finished with lines like “I want to die,” “I love to suffer” and “I’m going to kill myself” pepper meme pages across the globe. It’s practically the norm. It seems then that our generation is casually suicidal — constantly toying with the idea of death, tiptoeing on that fine line between humor and nihilism.

This focus on dying is a prominent and unique theme of our generation, one that is having palpable repercussions not just on humor culture, but also on the depiction of mental illness across society.

Upon first glance, death jokes seem to be just that: jokes. If anything, some argue, jokes centered around suicide and depression can normalize mental illness; after all, the best way to destigmatize any topic is to spread awareness and discuss the issue, and mental illness should be no different. Additionally, death jokes could serve as a casual platform for people with mental illness to express their feelings and feel normal.

Finally, introducing these topics into our everyday culture could help lessen feelings of isolation, as those suffering from depression or suicidal thoughts could realize that their feelings are not only valid, but also more commonplace than thought.

While some of these arguments do have truth to them, experts have actually spoken out against the death-joke culture. As counterintuitive as it seems, making death jokes does not necessarily destigmatize mental illness. Instead it trivializes its challenges.

Dan Reidenberg, the executive director of Suicide Awareness Voices of Education (SAVE), spoke about the issue to The Huffington Post in a 2016 article.

“It’s actually demeaning to those with true illnesses that can’t easily stop these behaviors,” he said. “If we trivialize them into something else, we have done everyone a disservice.”

Not only is it demeaning towards those who suffer from mental illness to joke about the topic, but these death-centered jokes can also falsely perpetuate the idea that mental illness is no longer a serious issue. After all, it’s light enough to joke about. The reality is that teenage depression rates have skyrocketed in the past few decades.

According to a study reported in Pediatrics, a well-respected medical journal, the percentage of teenagers who have experienced a major depressive episode in the past year has increased from 8.7 percent in 2005 to 11.5 percent in 2014. There was a 37 percent increase in prevalence in only nine years.

While some of this can be attributed to extraneous factors like better antidepressants and a more positive attitude about therapy (both of which may have led to people being more likely to report their symptoms), the trend across multiple stories reflects the idea that mental illness is becoming an increasingly prevalent issue.

Simply put, it isn’t something to joke about, and it definitely isn’t something to risk trivializing.

So it’s obviously a problem that our humor is so centered around depression and suicide. But what’s especially intriguing about the whole ordeal is that, despite at least subconsciously knowing that death jokes aren’t appropriate, we all continue to make them — myself included.

We pride ourselves on how much we care about bettering our world; that’s why we pursue the majors we do, and that’s why we join the organizations we join. But in perpetuating this style of humor, it seems like we’re turning around and stabbing ourselves in the back.

We are ostracizing a larger and larger portion of our community for the sake of our own entertainment, and we’re basically aware that we’re doing so. It’s hard to curb a bad habit. In the days that I spent researching and writing this article, I probably joked about how much I wanted to die because of it. But this is an issue that demands more of our attention.

We as a community need to stop trivializing mental illness and start problem-solving. We need to be aware of what we say, how we say it and how it affects others. We need to be better — it’s our responsibility not just as individuals or as Hopkins students, but as members of a global community, as people who care.

Nicola Sumi Kim is a freshman majoring in Global Environmental Change and Sustainability and Writing Seminars. She is from London.