In early September, Mayor Catherine Pugh signed a bill from the City Council designating Oct. 4 as Henrietta Lacks Day.

Lacks was an African-American patient of Johns Hopkins Hospital in the 1950s diagnosed with cervical cancer. Her cells were taken without her consent and were used to create the first strain of self-replicating cells, known as HeLa cells.

Since then, they have led to some of the most significant discoveries in medical research. Public interest in Lacks and her family peaked upon publication of Rebecca Skloot’s best-selling book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, which HBO adapted into a movie this year.

Pugh’s bill is not the first Henrietta Lacks Day legislation. This summer, Gov. Larry Hogan announced Aug. 1 as Henrietta Lacks Day in Maryland. Baltimore County Executive Kevin Kamenetz also announced this year that the first Saturday of every August will be recognized as Henrietta Lacks Day in Baltimore County.

At the time of Lacks’ death, there was no standard requirement for institutions to notify patients that their tissues would be taken for research purposes. Today, people continue to question the integrity of the Hospital’s actions and some members of the Lacks family demand compensation.

Kim Hoppe, director of public relations and corporate communications at Hopkins Medicine, commended Pugh’s decision in an email to The News-Letter.

“Johns Hopkins applauds efforts to raise awareness of the life and story of Henrietta Lacks,” Hoppe wrote. “Since 2010, Johns Hopkins has worked closely with members of the Lacks family to develop a series of programs to recognize and honor Henrietta Lacks.”

Students like freshman Patrick Rao are curious about what this day entails for the city and for Hopkins.

“Is the school going to do anything to celebrate the day?” Rao asked. “It would be awesome if Hopkins did something every October to remember her.”

Students like freshman Kristofer Madu believe that the Hospital has yet to answer for taking Lacks’ cells.

“Although this whole situation may seem in the past, in actuality its relevance remains,” Madu said. “The Johns Hopkins Hospital and community should continue to strive to right the wrongs of the past and to grow to maintain its status as an internationally respected top-tier medical institute.”

Freshman Alex Eremiev said that Pugh’s decision is an appropriate tribute.

“It’s important to spread awareness about what she did for science,” Eremiev said. “A day dedicated to her is a good way to remember her.”

Other students like freshman Rebecca Penner suggested that the controversies surrounding Lacks and the Hospital have negatively impacted the University’s image outside of Baltimore.

“When [my Grandma’s friend] heard I was going to Johns Hopkins, she wasn’t congratulating me or anything because she said that the Henrietta Lacks stuff ruined the reputation of Johns Hopkins,” Penner said.

Members of the Lacks family remain divided over whether Hopkins and Skloot have distorted Henrietta Lacks’ legacy.

Earlier this year, Lacks’ son Lawrence Lacks announced a lawsuit against the Hospital and accused Skloot of misrepresenting his family in her book, while Skloot claimed that she obtained source material and consent from other members of the family.

In an email to The News-Letter, Anthony McCarthy, director of communications and community engagement for Mayor Pugh’s office, expressed his hopes that Pugh’s decision would draw more attention to Lacks and her contributions to medical research.

“It is my hope that this special day will renew interest in her life and legacy,” he wrote.

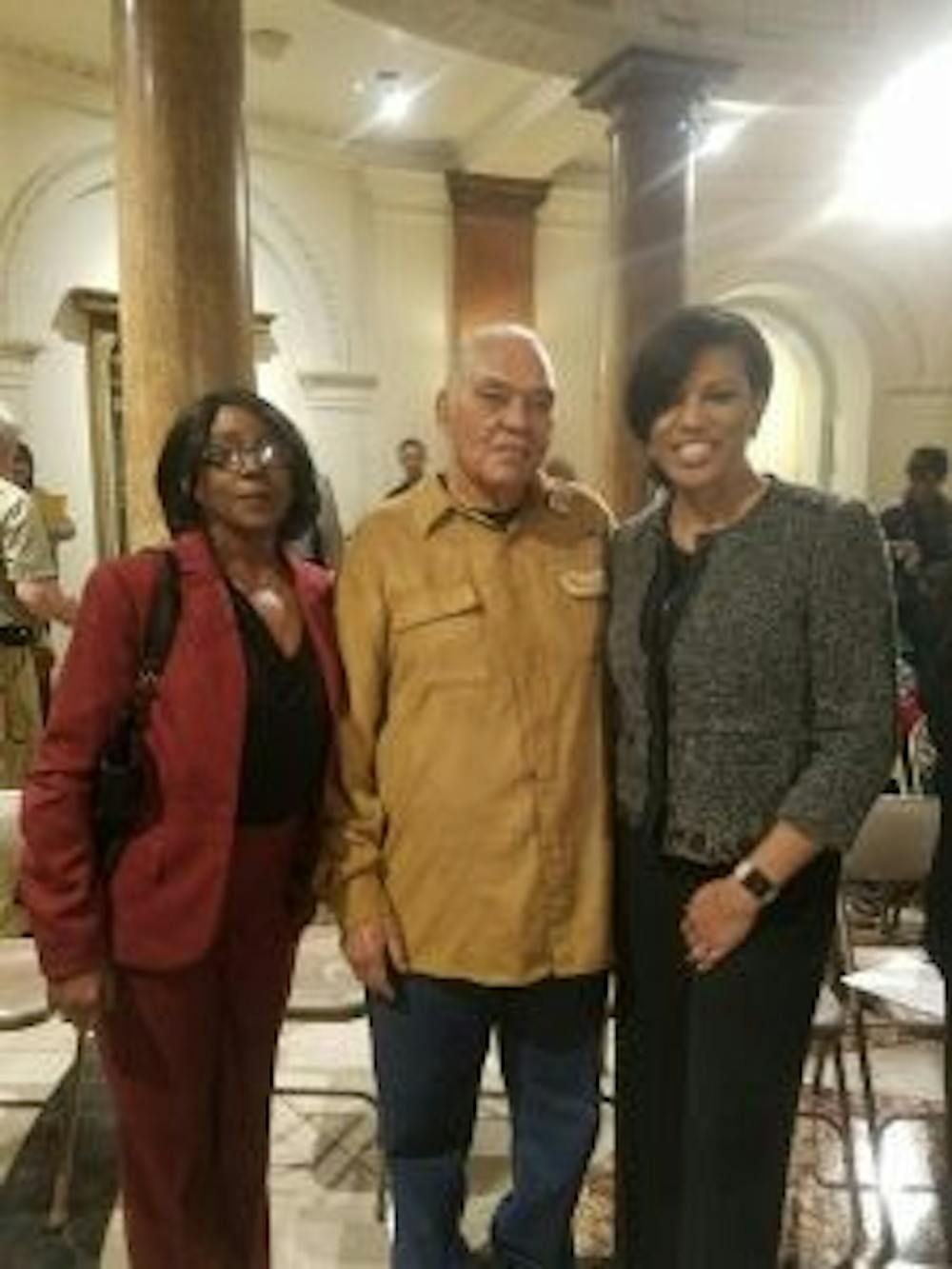

Correction: The original photo caption misidentified members of the Lacks family.