The University instituted a new child accommodation policy for graduate students over the summer. This program allows new parents to take up to eight weeks off to care for their children.

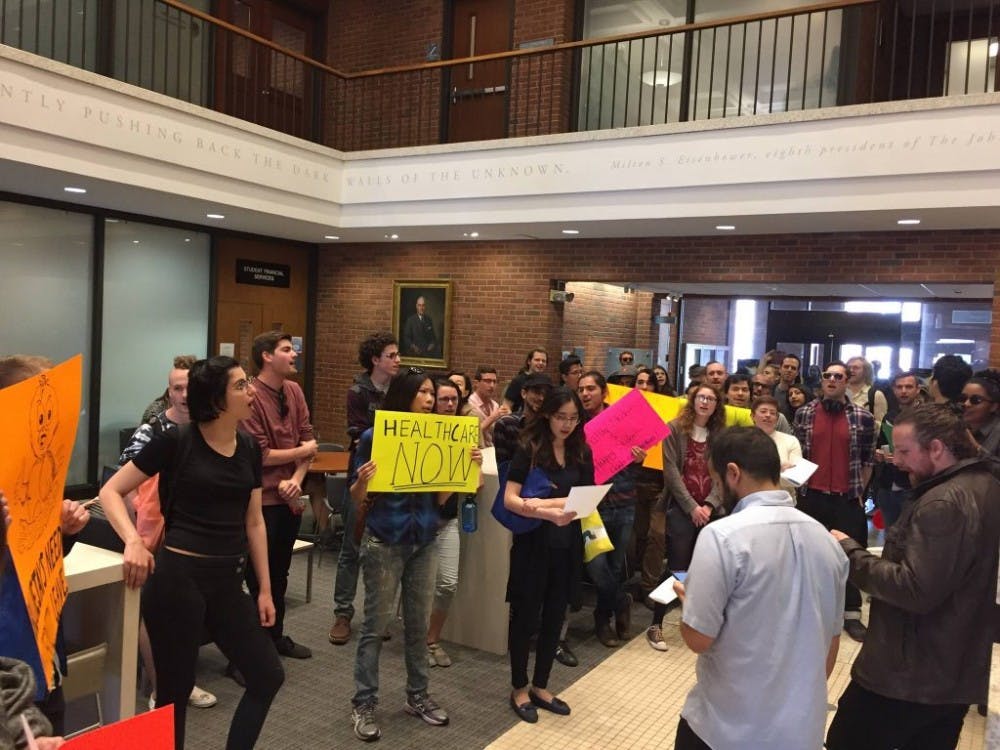

For months, Teachers and Researchers United (TRU), an organization of graduate students, has advocated for better healthcare, including family leave for graduate student parents. TRU submitted their demands to the administration at the end of last semester.

Casey McNeill, a PhD candidate in sociology and member of TRU, said that the organization spoke with graduate students last year and found that they were dissatisfied with the University’s healthcare plan.

Graduate students commonly cited the lack of parental leave accommodations as a pressing problem with their current healthcare policy. McNeill explained that Hopkins students received worse benefits than those at the University’s peer institutions.

“Both seeing how much grad students were being affected by high medical bills and seeing that other peer institutions give grad students a little bit more support was the logic behind doing a major push for the University to make some changes,” McNeill said.

The policy took effect on July 1 and applies to full-time graduate students and postdoctoral trainees.

The University instituted a similar policy for faculty and staff, which allows for six weeks of leave immediately following the birth of a child.

Executive Vice Provost for Academic Affairs Stephen Gange wrote in an email to The News-Letter that the University aims to better support students with new families.

“University leadership recognized that changes were needed to improve the support of graduate

students and postdocs who, like faculty and staff, are balancing professional and personal commitments with the arrival of a new child,” Gange wrote.

While some of the University’s peer institutions offer longer leave periods, others offer significantly shorter periods. The University uses an official list of peer institutions known as the Consortium on Financing Higher Education (COFHE) to compare its policies and standards.

At Yale University, students may request a semester of parental relief, which entitles them to eight weeks on leave and a full semester of modified academic expectations. The University of Pennsylvania (UPenn) offers one or two semesters. Comparatively, Duke University only offers three weeks of parental leave.

Allison Young, a PhD candidate in sociology and expecting mother, raised concerns about financial subsidies for students on parental leave. She said that the last thing expecting parents want to worry about is losing their income.

Young also discussed the terms of her upcoming leave with her supervisor, Renee Eastwood, the director of graduate and postdoctoral academic affairs at the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, and other administrative staff.

“The purpose of it was to hash out on an individual level the implementation of the policy,” Young said. “The policy ends up being very individualized for each student, and circumstances will be different. It’s good for it to be flexible and accommodate students’ needs, but there’s also a risk that students won’t all benefit equally from it.”

The policy also states that “if the student is receiving tuition, stipend support and benefits from a training grant, fellowship or scholarship, these will remain unchanged during the accommodation period contingent on the policies of the entity providing the funding.”

Yale offers parental relief in the form of a financial aid stipend, and the parental leave offered at Duke is fully paid, according to their respective policies.

However, funding for students on leave at UPenn is deferred during the period of leave. At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), students are not eligible to receive a stipend unless they work as Resident Advisors or Teaching Assistants.

McNeill said that the new policy is important because instances of parental leave were previously decided by supervisors on a case-by-case basis.

“It was totally contingent on your advisor making a decision about how much time you could get off,” she said. “Some people could manage to get some kind of accommodation from their advisor, but it really puts a lot of strain on that relationship between the worker and their advisor if these kinds of things are arbitrary.”

She added that TRU had some concerns about the implementation of the policy, mostly regarding the difficulty that could arise if advisors pressure their students not to take the full eight weeks of leave.

“The advisor-advisee relationship can be hard to negotiate,” McNeill said. “If you strain that relationship that can have a lot of negative consequences. If there’s a grad student who wants to use the full leave... In practice is it going to be difficult to take the full eight weeks?”

Gange wrote that the deans from every University division unanimously endorsed the policy. She also said that by approving policies for graduate students, staff and faculty, the University aimed to advance a culture that embraced the leave policies.

“The policy codifies this entitlement to all graduate students and postdocs and provides clear and unambiguous support to students who were previously in a position to negotiate these issues by themselves,” Gange wrote. “The Provost’s Office will be monitoring the implementation of this policy and encourages any student to report any concerns to either divisional or central leadership.”

Young said that some students in certain departments or with certain advisors may have more trouble than others.

“Historically, students have been negotiating on an individual basis with their advisors — but it hasn’t been uniform,” she said. “This policy takes a step toward creating a baseline but it doesn’t actually go all the way to making a uniform policy for everyone because there is that individual negotiation component.”

Gange explained that the University established the Provost’s Advisory Team on Healthcare (PATH) to review concerns about the new policy and make recommendations to the University’s leadership.

“First, it will work to collect and coordinate concerns regarding graduate student and postdoctoral scholars’ healthcare experience at Johns Hopkins,” he wrote. “The committee will assemble these concerns and assemble relevant data.”

According to McNeill, the policy also does not address non-parental family obligations such as sick family members. Gange wrote that it was difficult to anticipate any possible situations, but that accommodations for family emergencies would be handled on an individual basis.

McNeill added that TRU was planning to communicate with graduate students to determine the success of the new policy.

“When we really come together, have a clear message and put demands on the administration, we do get some response,” McNeill said. “What we really need is a more sustained way to have our needs recognized and really taken seriously by the administration, rather than having these campaigns over every single issue.”