David Harvey, distinguished professor of anthropology and geography at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York (CUNY), spoke to a crowd of around 200 in Hodson Hall about his work bringing critiques of capitalism back into public discourse.

The Arrighi Center for Global Studies hosted the event on Thursday, April 27.

Before moving to CUNY, Harvey was a professor of geography at Hopkins. He has published numerous books and articles, many of which focus on capitalism and Karl Marx’s Capital: Critique of Political Economy.

“I’ve had a project over the last 15 years or so, since I’ve moved to CUNY, which is about making Marx more accessible to the public,” Harvey said. “[What] continues to be a challenge is to simplify without being simplistic.”

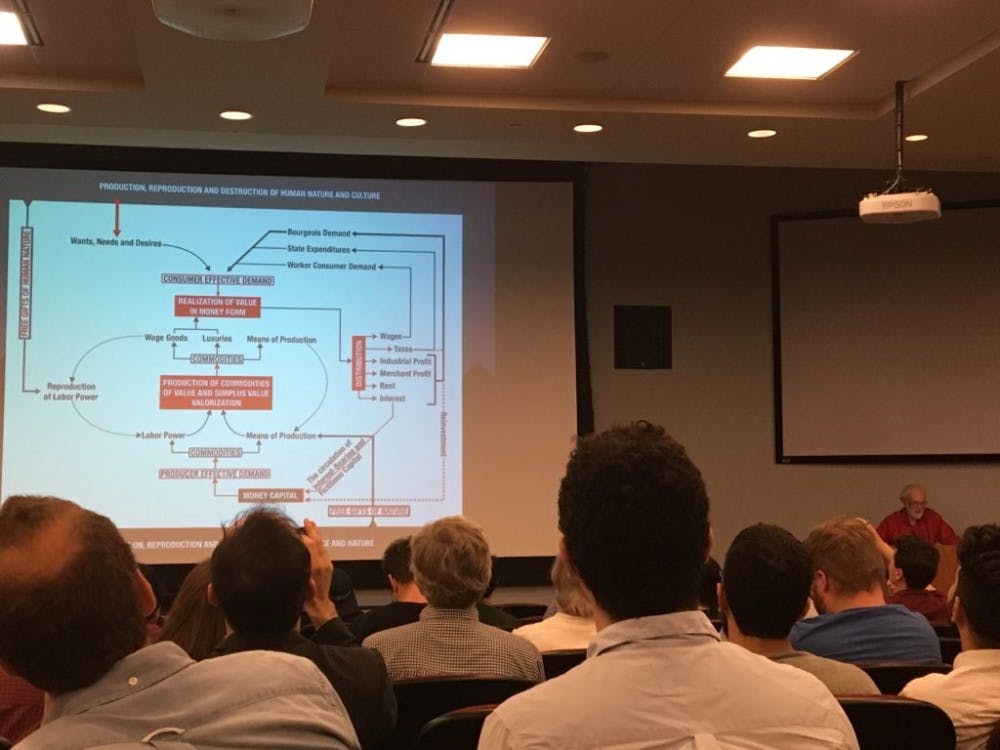

Harvey explained that he has worked to achieve this goal by developing a visual representation of Marx’s ideas. He used his background in geography and graphics to create a comprehensive diagram.

“The inspiration for this particular static version comes from the water cycle,” he said.

According to Harvey, capital, like water, moves through various stages. Capital is accumulated wealth in the form of money or other assets, like land, labor and industrial goods.

For Harvey, capital is value in motion. As soon as it stops moving, it is immediately worthless. Therefore, if a good has no market through which it can be exchanged, it becomes worthless.

“Marx has thought out a fairly consistent definition of capital, which is value in motion,” he said. “Capital, in order to maintain its value, has to keep in motion. It must keep the cycle going.”

According to Marx, profit is only possible in a capitalist system through the exploitation of workers’ labor power. For example, a capitalist sells a washing machine for $300, though the process costs $250, with the parts costing $200 and the labor $50. Marx argues that the reason why the capitalist makes a $50 profit is by undervaluing the labor of his or her workers.

For Harvey, the history of capital is the history of wants, needs and desires.

As wants, needs and desires of consumers change, demands for products change too. Capitalism has fundamentally changed social relations by creating an economic system where most individuals have no choice but to sell their labor power for a wage that is significantly lower than the capitalists’ profits.

Harvey identified the long-term trend of declining profitability in the production of material goods in the West. As profits have declined, Harvey said, workers’ wages have been suppressed. Because workers have less money to spend on their wants, needs and desires, profitability has declined further because there is less demand for capitalist products.

According to Harvey, the state makes up for lowered demand by injecting money into the economy, for example through military expansion or building suburbs. The massive spike in military spending and demand for industrial products during the Second World War accelerated the American economy’s recovery after the Great Depression.

“There was a stake in manipulating environmental transformations and wants, needs and desires to make a market and to make absolutely sure there were places for capitalists to make a profit because the demand was there and was strong and was coming from the state,” he said.

States helped capitalists by constructing new wants, needs and desires, like home and car ownership, to encourage the continued expansion of production. This state spending was only possible through the rapid expansion of capitalist states’ national debts, according to Harvey.

For a more contemporary example, Harvey cited the housing bubble that sparked the 2008 financial crisis.

After the bubble popped, the housing market exploded, stopping capital from circulating.

Because capital must remain in motion to retain its value, some institution needed to recreate a market after the Great Recession.

Harvey went on to say that the 2009 stimulus package that the Obama administration released to stimulate demand in a floundering economy allowed capital to flow again, restoring markets and profitability.

But he added that the American state had to take on billions of dollars in debt to spur demand again and recreate the supposedly “free” market.

He elaborated on Marx’s idea that a free market without restraints will lead to the rich becoming richer and the poor becoming poorer.

He said that such a system is focused on the accumulation rather than the flow of capital. Accumulation can often disrupt the capital cycle and cause the system to deteriorate and spiral out of control, creating financial crises like the Great Recession in 2008.

“The difference between a circle and a spiral is that a circle is knowable and containable and calculable, but a spiral is not,” he said. “There is a very good reason why we have that English expression of things ‘spiraling out of control.’”

Harvey said that while the global money supply is increasing, the only way that capitalist countries are able to access more money is through debt financing, where they borrow money from banks and other nations to pay off their previously accumulated debts and new expenditures. He cautioned that debt financing is not sustainable and may lead to serious problems down the line.

Harvey argued that late capitalism is flooding the world with debt, emphasized by the fact that the world’s total debt is in excess by 225 percent of gross domestic product (GDP).

Because capitalism relies on the creation of new debt to make sure that capital continues to move around, the total debt cannot be significantly reduced without severely endangering the global capitalist economy.

In the question and answer segment, Associate Professor of Sociology Joel Andreas asked Harvey whether debt accumulation would lead to class struggle in the future.

Young people, individual households and entire nations struggle to borrow more money to pay off their ever increasing debts.

Andreas explained that heavy student loans and increasing property prices mean that many Americans will never escape debt in their lifetimes.

Harvey agreed with Andreas’ proposition but stressed that the sites of production, like factories, and sites of distribution, like ports or highways where capital is shifted, will remain important zones of conflict for future struggles.

Another audience member asked Harvey to elaborate on whether value, the economic measure of a good or service, can change.

In response, Harvey stated that value is dynamic. He said that nations often try to impose their own value systems upon other countries, citing structural adjustment policies of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank that he said have undermined economies in the developing.

But Harvey emphasized that the policies that governments in the West implement, like restrictions on spending and lower taxes on corporations to supposedly spur economic growth, do not benefit the majority of a nation’s citizens. Instead, the wealthy, especially capitalists, profit from such policies.

For example, Harvey said that German corporations benefited from the creation of the Euro, the common currency that unites 19 European nations, while the German government did not.

He also stated that the upper class profited from the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and would have benefitted from the recently cancelled Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), two treaties designed to remove trade barriers between the United States and other countries.

In contrast, the working class and even the United States itself did not benefit from NAFTA and would have suffered from the TPP. Harvey believes that such examples represent the conflict within capitalism today.

“Capitalism is doing very badly, but the capitalists are doing extremely well,” he said.

Meghaa Ballakrishnen, a graduate student in the History of Art department, was familiar with Harvey’s work prior to attending the lecture.

She is currently sitting in on a class in the political science department that focuses on Marx’s value theory and appreciated Harvey’s approach to teaching Marx’s ideas.

“I think it’s really important to make Marx legible and I think [Harvey’s] done it better than anyone else,” she said. “One of the ways he does it is by being true to Marx while also being very clear and direct.”