"You’re a man now! Stop crying.”

My nine-year-old self shuffles uncomfortably in the wooden chair but not because of the summer heat. I do not dare look my grandfather in the eyes, since doing so would be seen as a sign of defiance. The more he says these words, the more my tears flow even though I understand him perfectly. I try to find the words in my limited Chinese vocabulary that will satisfy my stern grandfather.

My grandfather is not a large man by mass, but his voice can intimidate anyone who disagrees with him or any of his principles. And his definition of a man is traditional — a stoic figure that can shake off any kind of abuse, physical or verbal. Clearly, I do not fit that archetype. I struggle to contain my tears as I breathe in and out heavily.

Before that summer, I was known as the crybaby of the school. I was overly sensitive to anything — name-calling, small scrapes from falling on asphalt or even forgetting to bring my completed homework to school.

My grandfather probably could not believe that my parents would raise their son, a man, as they raised me. He always talked about how my mother raised herself and her younger sister on her own, and that even a girl was tougher than I was.

At the beginning of that summer, I cried almost every day. But as the days passed, I cried less frequently, conditioning myself to be the man my grandfather wanted me to be and not to show any signs of weakness. Eventually my grandfather returned to China, but I continued to put on a stoic mask for years afterwards. I had learned how to be my grandfather’s definition of a man.

When I started playing violin in my junior high school orchestra, there were only about four other students in my year, and I did not know anybody because it was a new school for me. One of them, Hannah, tried talking to me and we soon found out that we shared five out of our seven classes. We also had a similar interest in sports, but more than anything I really just enjoyed having someone I could talk with to pass the time in orchestra when we weren’t playing music.

One day, she asked me a question I won’t ever forget.

“Why don’t you smile or laugh more, Scott?”

Dumbfounded, I stood there not knowing how to answer her seemingly simple question. Even though I felt happiness when we talked, I was unable to translate that emotion to my face.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I just don’t feel like it.”

I continued to ponder her question throughout the rest of the day, but it wasn’t until much later that I was able to piece the puzzle together. I realized that by conforming to my grandfather’s idea of a man, I had not only caused myself to stop shedding tears, but I had also stopped smiling.

The next day in school, I made an effort to smile more. Without seeing how I looked to others, I felt incredibly awkward and wanted to continuously wear my stoic mask. It felt comfortable to me at that point. Throughout the rest of junior high, I struggled to show any kind of emotion, whether it was happiness or sadness, anger or excitement.

However, I had planted the seeds of unlearning how to be my grandfather’s idea of a man.

Even to this day, I still tend to put on an emotionless face at times. When my friends’ parents see me, they ask if I’m happy. Some of my friends call me a sad boy.

However, I realize that unlearning what it means to be a man does not happen instantly. I feel much more comfortable laughing and smiling with my friends now than I did in the past. Sometimes, I feel even brave enough to shed a tear.

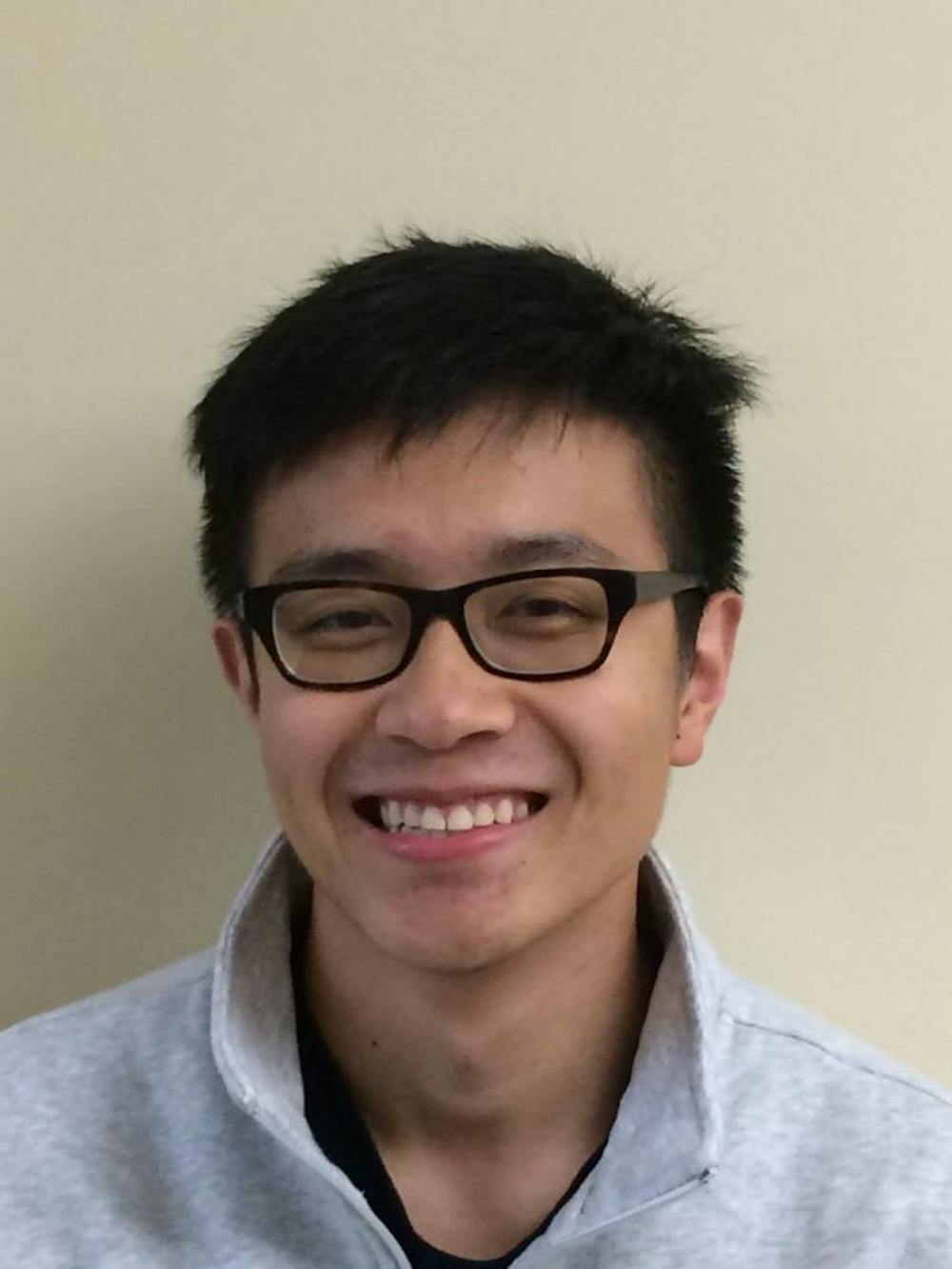

My grandfather would no doubt be disappointed in me if he were to see all of the times I cried since that summer. But now I feel like I have the courage to face him non-stoically. To face him as a man.