Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) has long been hailed as a noninvasive medical technique that produces intricately detailed images of one’s brain and brainstem areas. In fact, the MRI is more effective at detecting abnormalities in the brainstem than many other scans, such as CT scans or X-rays. A study published in Nature reveals that MRIs can even be used to predict whether or not infants are likely to contract autism at an early age.

Dr. Joseph Piven, one of the leaders of the study, says that early biomarkers in brain development can often be used to identify infants who have a high risk for autism even before actual symptoms begin to emerge. Piven is currently the Thomas E. Castelloe distinguished professor of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“Typically, the earliest an autism diagnosis can be made is between ages two and three. But for babies with older autistic siblings, our imaging approach may help predict during the first year of life which babies are most likely to receive an autism diagnosis at 24 months,” Piven said, in a press release.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) has become an increasingly common phenomenon in America. In fact, it is estimated that one out of every 68 American children is diagnosed with ASD every year. There might also be a genetic component that adds to the risk of developing ASD, since children with older siblings that have ASD are more likely to also carry the same conditions.

Prior to two years of age, it is extremely difficult for physicians to precisely identify the infants that are at high risk of developing autism. After this age threshold, however, it is much easier and much more efficient to identify those that demonstrate characteristic tendencies for ASD.

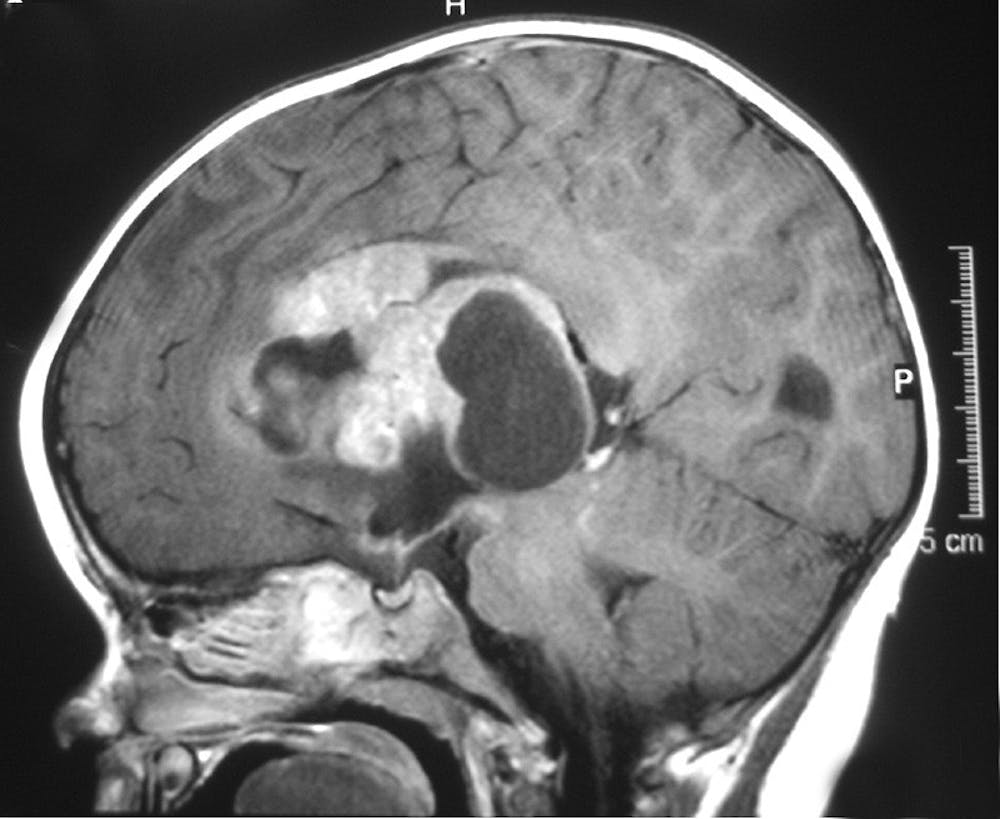

Piven and the rest of his research team took very specific procedures to carry out the research process. They performed MRI scans on infants gathered from three different age groups: six months, 12 months and 24 months. It turned out that infants with autistic symptoms commonly experience brain overgrowth during the first two years of their lives. This increased, almost abnormal growth rate in the brain causes many children to have social deficits, although researchers cannot proficiently explain how the two variables do not have a causal, direct relationship.

This research pioneered by Piven’s team is actually a project that was started at the Carolina Institute for Developmental Disabilities (CIDD) at the University of North Carolina. The project is in collaboration with other clinical research institutions such as the University of Washington, Washington University in St. Louis, the University of Minnesota, the College of Charleston, New York University and The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. The project even collaborates with a few universities in Canada, such as McGill University and the University of Alberta.

It is widely accepted that social behaviors with autistic trends tend to emerge during the second year of a child’s life. Researchers investigated various data including age, gender, brain volume and surface area before reaching the conclusion that there is a specific criteria crucial to pinpointing which group of children might be more prone to developing autism by the time they reach two years-old.

This computerized set of criteria is especially useful to parents who have already given birth to a child with autism. If the couple has a second child, they can use such a method to predict whether their second child will also have autism. It turns out that the test gives valid results 80 percent of the time.

“We haven’t had a way to detect the biomarkers of autism before the condition sets in and symptoms develop,” Piven said in the press release.

However the researchers are now embarking on a renewed mission to make such speculation a highly possible reality.