In a day and age where former Klansman David Duke has over two hundred thousand followers on Twitter, debonair fascists are infecting political discourse at every level and our president is essentially the Jerry Springer version of Benito Mussolini, having some uncomfortable thoughts about race relations in the United States is quite a good thing.

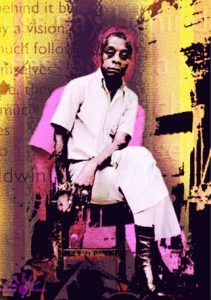

Enter Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro, a documentary built around iconic author James Baldwin’s incomplete manuscript for Remember This House, a memoir structured around the deaths of three men: Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.

Fun fact: the publisher McGraw-Hill sued Baldwin’s estate after the author’s death to get back a two hundred thousand dollar advance for Remember This House.

You might know McGraw-Hill as the company that makes all those horribly over-priced textbooks you used in grade school. Now you can know them as the massive company that sued a dead American icon.

I Am Not Your Negro premiered in September of last year at the Toronto Film Festival to fairly universal acclaim, including an Oscar nomination, and was widely released in early February of this year. The film has been heralded by the A.V. Club, The Wall Street Journal and Time.

The director, Raoul Peck, is a Haitian filmmaker whose presence in the American film canon is relatively limited, although some may know him for the film Sometimes in April, a drama, starring Idris Elba, about the Rwandan genocide. Peck’s approach to this film is an interesting one, and the project itself was ambitious.

Basing an hour-and-a-half long documentary on a less-than-50-page, 30-year-old unfinished manuscript was, to say the least, a bold venture. Somehow, Peck pulled it off and did so in a way that defies categorization.

I Am Not Your Negro is indeed a documentary in the sense that it is factual. However, it’s not as simple as that – this movie is a collage, an eclectic mix of old film clips, interviews, news reels, cellphone camera video and photographs.

These varied images are all linked together by Baldwin’s words, connecting them to the murders of three men and the battle that they and the author fought. Peck’s encapsulation of Baldwin’s brilliance and his unique perspective is made all the much better by the fact that Samuel L. Jackson is the narrator.

Frankly, I can not tell you how to feel about this movie. I can not offer any insight into its meaning and its implications in contemporary American society. I am just a juvenile 21 year old with a cinema fixation and an outlet that I probably do not deserve. This movie will no doubt mean different things to different people, but I will tell you how I Am Not Your Negro made me feel, as a upper-middle-class white liberal.

It was a reminder that complacency is dangerous, that racism is not some sickness that I can pretend to have been cured of. Baldwin’s words combined with Peck’s vision piece together a discriminatory system, one which is built on inaction as much as it is oppression.

The film critiques that common idea that “things are better than they were.” Footage from the riots in Ferguson with the militarized police out in force are juxtaposed against clips of Martin Luther King Jr. marching while rabid white supremacists wield the swastika with pride.

I Am Not Your Negro uses contrast to create unity. It links three different men together using Baldwin’s relationship with each and draws parallels between past and present using the words of a genius. The movie is as relevant to the murders of black men and teenagers at the hands of police as it is to the murders of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and King.

This relevance is so poignant that it feels like Baldwin is still alive, that Remember This House is being written at this very moment, that racial problems in this country have not gone away just because black people can now (contemporary polling laws non-withstanding) vote. I Am Not Your Negro reminds you that it is easy to think that things have improved, but that does not mean they actually have.

I saw the movie at The Charles Theatre, and when it ended, I walked to the bus stop on the corner of Charles Street and North Avenue to wait for the bus back to campus. Overlooking that corner, there is a billboard. Whatever was advertised on it was evidently torn off at some point, because now the sign is painted a flat grey. Across that grey background, a question is posed: “Whoever died from a rough ride?”

Beneath that, in smaller print, is written, “The whole damn system.” That sign, like the movie, makes a point: Racism is not gone and still infects so many aspects of American life.

Look at the place where we go to school. Laughing about the dangers of Baltimore City, you are a Hopkins student nestled comfortably in your high-cost intellectual bubble. This is an easy response to an unequal system which you are a part of. Nobody exists separate from their environment, and Hopkins is as much a part of this city as violence, drugs and poverty are.

The Baltimore we claim and the Baltimore that raised and killed Freddie Gray are not mutually exclusive. The two exist together, but only if you are willing to recognize them as one and the same, to recognize that racial inequality is real and it is a system in which we all participate. To me, that recognition was the end of I Am Not Your Negro, and in its attempt to educate viewers about the reality of American life, it is likely unparalleled in its gravity.

I Am Not Your Negro is currently playing locally at The Charles Theatre.

Overall rating: 9/10