In a recent study published in the journal Molecular Cell, scientists discovered that DNA may make up only about half of the material found in chromosomes. In fact, up to 47 percent of a chromosome’s makeup may consist of a sheath, or a protective structure, surrounding DNA.

Researchers suggest that this sheath could play an essential role in keeping chromosomes separate during cell division, which would help prevent mutations that could lead to birth defects, cancer and other diseases.

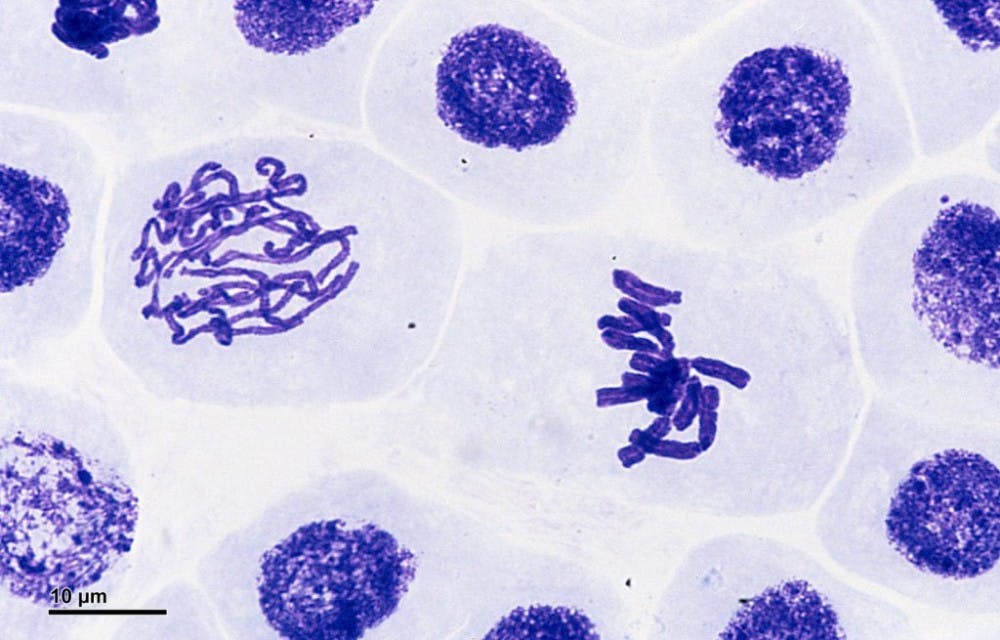

Using a process called 3D correlative light-electron microscopy (3D-CLEM), researchers from the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, the Kazusa DNA Research Institute in Japan, the National Cancer Institute in the United States and the University of Liverpool in the United Kingdom were able to form an image of chromosomal structure and use this image to study the chromosome in great detail.

3D-CLEM, which combines light and electron microscopy with modelling software, allows researchers to produce high-resolution images and observe the presence of the sheath on all 46 human chromosomes.

In analyzing the 3D-CLEM images, scientists found that only 53 to 70 percent of chromosomes may be made of chromatin, which contains DNA and supporting proteins. Previously, scientists had believed that chromosomes were tightly packed structures of DNA and histones.

Although chromosomes were discovered in 1882, their exact makeup is still unknown. This may be the result of technological limitations that prevented the detection of the sheath and the other materials that surround it until recently.

“The imaging technique we have developed to study chromosomes is truly groundbreaking. Defining the structure of all 46 human chromosomes for the first time has forced us to reconsider the idea that they are composed almost exclusively of chromatin, an assumption that has gone largely unchallenged for almost 100 years,” Daniel Booth, a research fellow from the University of Edinburgh who co-led the study, said in a press release.

“We now have to re-think how chromosomes are built and how they segregate when cells divide, since the genetic material is covered by this thick layer of other material.” Bill Earnshaw, a professor at the University of Edinburgh’s School of Biological Sciences who also co-led the study, said in the press release.

The results of the Edinburgh study support the findings of a study published in 1925 by Genetics. In an article titled “The Role of the ‘Chromosome Sheath’ In Mitosis, and Its Possible Relation to Phenomena of Mutation,” Charles W. Metz, a member of the Department of Genetics at the Carnegie Institute of Washington, noted possible functions of the sheath. In the study, Metz concluded that chromosomes that exhibited this sheath might be able to separate more easily during cell division.

Metz also described the chromosome sheath as “a gelatinous layer of material” and noted that many scientists typically disregard to it due to the fact that it is usually invisible in common imaging technologies.

Although he stated in the Genetics article that it is uncertain whether or not the sheath is a typical part of chromosomes in general, Metz also predicted that the sheath may play a crucial role in cell replication and may be involved in preventing mutations.

Ninety-one years later, Metz’s hypotheses may be confirmed. With new imaging techniques such as 3D-CLEM, scientists may now be able to observe the role of chromosome sheaths in cell division as well as investigate their structure.

Understanding the chemical makeup of the sheath as well as its role will help scientists better understand the process of random mutation during mitosis. Perhaps in the future, scientists may also be able to alter the chromosome sheath and intercept harmful mutations.