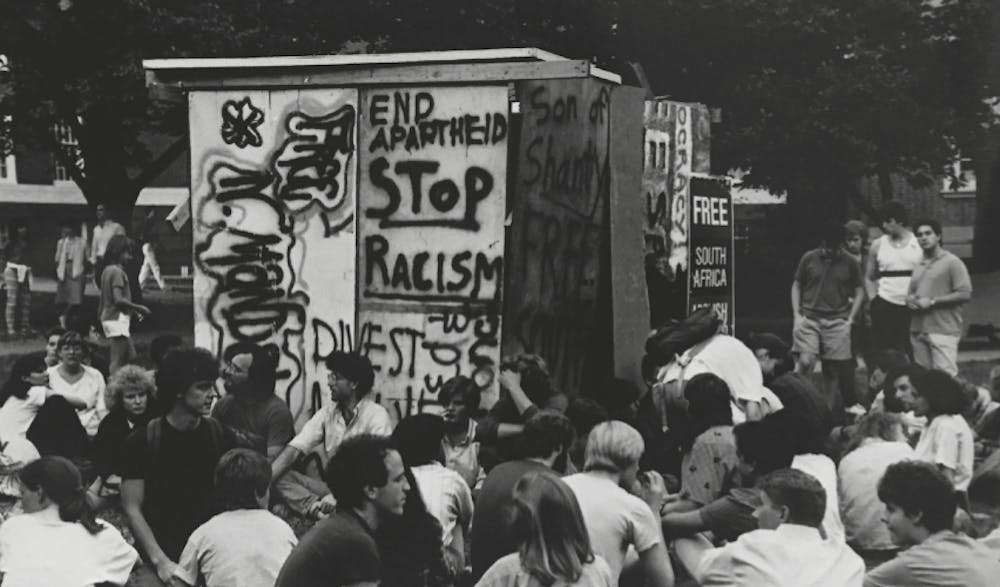

The Hopkins Board of Trustee notes are only available 25 years after they are written; therefore, only records before 1991 are available. From 1985 until 1987, Hopkins undergraduates, graduate students and a few faculty protested the University’s investment in apartheid South Africa by erecting mock shanty towns around campus under “the Coalition for a Free South Africa.”

Only in the past few years have the Board of Trustees’ notes become public. They illuminate how the Board responded to student protest as well as how they reckoned with the morality of investing in a violent, white supremacist separatist state. They serve as valuable lessons for any current student activists.

The Board of Trustees is charged with “exercising fiduciary responsibility for advancing Johns Hopkins’ mission and goals in a sustainable manner, through wise stewardship of all of its resources for the common good and for generations to come.” From reading the 1980s notes, it is clear that the Board of Trustees seemed to have little regard for the “common good” part of its charge. It is obvious that only through extreme action could students hope to effect any change.

Initially, in 1985, the Board of Trustees only briefly mentioned the student protesters. They were annoyances whose presence was easy enough to ignore. The moral issues of apartheid were not brought up in the 1985 notes. University President Steven Muller at one time warns the Board that students will continue to question apartheid without offering any commentary on investment. It wasn’t until the spring of 1986 when three Hopkins Delta Upsilon fraternity brothers firebombed the mock shanty towns (luckily not killing or seriously injuring anyone) that the press took notice of the protesters.

The attempted murder of the protesters galvanized the press and student activists on campus, but it also pushed Muller. As reported by The News-Letter, student protesters found files on themselves along with newspaper clippings in the Office of Financial Aid; The administration was tracking their movements. In August 1986, Muller and the Executive Committee of the Board of Trustees prohibited “unauthorized structures on campus.”

This decree facilitated the arrest of 14 student activists on Sept. 29, 1986. During this arrest, at least one female student reported being sexually harassed by police officers and security guards, as reported by The News-Letter. The Board of Trustees responded to this PR nightmare in their notes by trying to find the best way to both quiet student protesters and avoid bad press.

Unfortunately for the Board, many members of the faculty now were on the side of the students. In one of the most illuminating notes on Oct. 2, 1986, Muller told the Board that if “faculty members would join with students... such a circumstance would be non-survivable.”

With the threat of a faculty-student alliance and the possibility of more bad PR, on Oct. 26, 1986, the Board instituted a selective divestment resolution — a good PR move, but not enough for the protesters, who wanted full divestment. From my limited access to the notes, it appears that the Board incrementally divested over the next few years and the protests petered out.

If the Board currently maintains the same culture and goals as it did in the 1980s, students can only hope for change through extreme action, such as sleeping outside in tents for months in order to cause bad press for the University. Until student lives were put in danger and the University suffered bad press after having their own students arrested, the Board of Trustees actively ignored student protests and the letters and petitions sent to them. Any moral appeal will only fall on deaf ears. Only affecting the University’s reputation will cause any change.

I doubt, had the brave students in the 1980s not been willing to be arrested, would the Board acquiesce to even selective divestment. Similarly, only the alliance of faculty and students caused the Board members to fear a “non-survivable” situation with regards to their investments.

I do wonder what the 1980s Board members think now about their investment in the violent and deadly apartheid system and the ensuing student response. At least 13 of the members from 1987 currently serve on the Board, and there is currently a student appeal from the group Refuel Our Future for the Board to divest from fossil fuel companies given the perilous state of our Earth. I hope that the Board listens to Refuel Our Future and other activist groups, but I believe that student activists must take lessons from our predecessors in the 1980s. Should the current Board of Trustees follow the path of the 1980s Board, only putting students’ lives on the line will move them to do anything.

Emeline Armitage is a junior International Studies major from Cleveland.