They call me the “Good Luck Charm.” It was a nickname that was not bestowed upon me immediately, of course. When I bundled up in layers and headed with my father to my first Army-Navy game at the age of eight in 2002, the Navy Midshipmen had been defeated by the Army Black Knights the year before. However, Navy would go on to steamroll Army in the game by a score of 58-12.

While I do not remember much about that particular contest, the Army-Navy games became a highlight for me each December. The routine of the day always followed a particular theme. I would get up the morning of the game and bundle up in layers upon layers — long underwear, fleeces, winters coats, gloves and hand warmers were the game day attire. The weather would be at or well below freezing, and if it was not snowing the day of the game, there was a great chance snow already covered the ground.

When my father and I arrived in Philadelphia, we would meet up with a number of close family friends. One of my father’s best childhood friends was a graduate of the Naval Academy and remains one of Navy’s biggest fans. His passion and exuberance would be on display during our pre-game tailgates. His face was adorned in blue and gold, he was stationed at the grill yelling out “Cheeburger, Cheeburger!” to anyone who wanted one. During the games, there was no one who would berate the refs louder for bad calls.

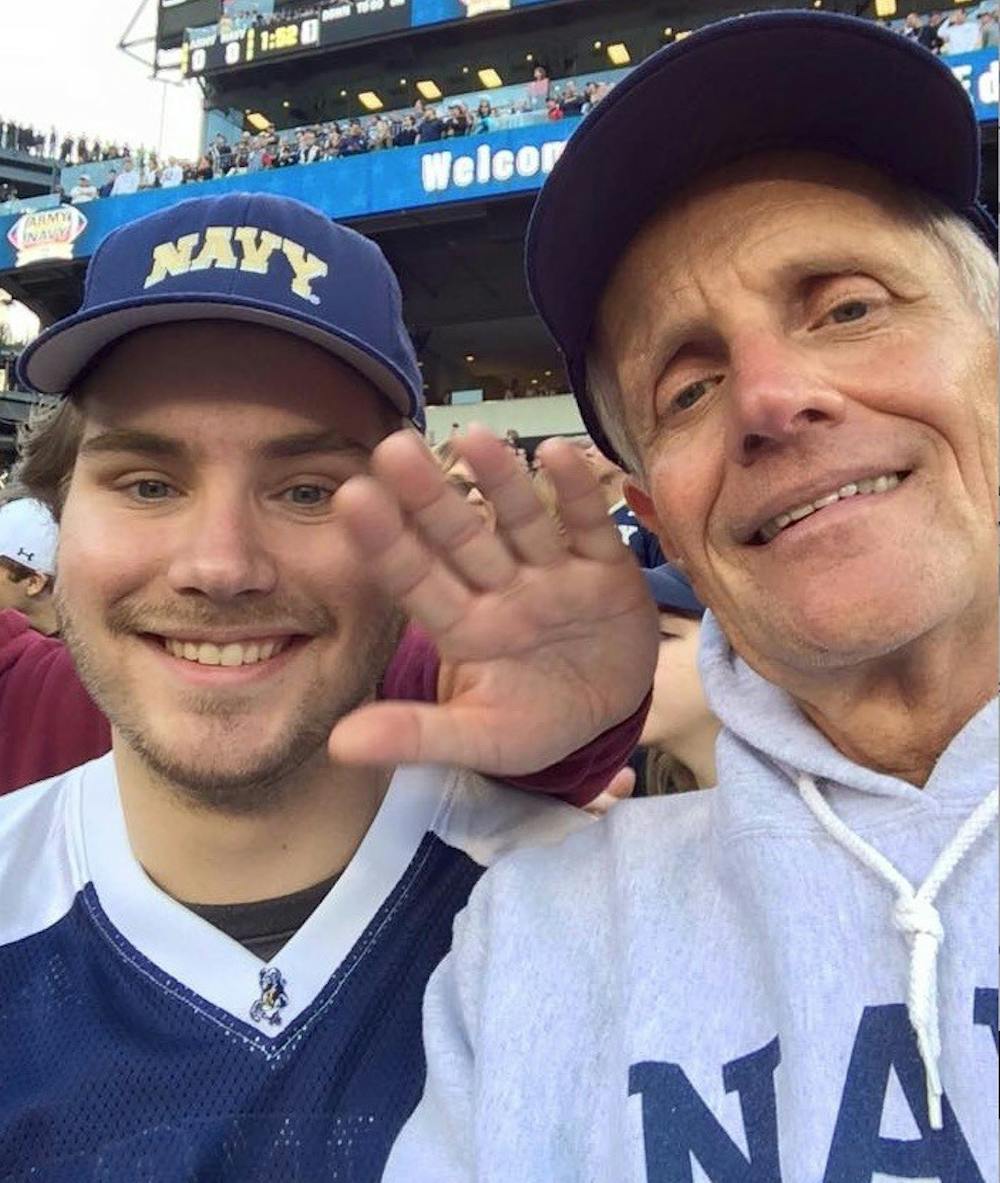

After the game, we would head back to our cars for a post-game tailgate, usually capped with a bowl of piping hot chili, the perfect antidote for a cold winter evening. The mood at the post-game tailgate was always celebratory. This is where my nickname comes into play. I have been to over a decade’s worth of Army-Navy games at this point in my life and have never witnessed a Navy loss.

Starting with consecutive win number five or so, my status as the “Good Luck Charm” really began to stick. And after 10, there was really no question anymore. I knew that once I went off to college, my ability to come to the game each year would be complicated, but I promised everyone that I would not fail them.

Unfortunately, exams prevented me from attending two consecutive Army-Navy games. Everyone in our tailgating group feared that this would mark the end of “The Streak,” but Navy kept winning. They pushed their victory total against Army in the series to thirteen in a row. My exam schedule was more forgiving last December, and I was able to attend as Navy won a thrilling 21-17 contest to push their run of dominance to 14 straight.

While I like to joke that I am Navy’s good luck charm, the Midshipmen really struck gold in 2002 when they hired a new, innovative coach who would turn the fortunes of the program around. The beginning of Navy’s winning streak in 2002 coincided with the arrival of Paul Johnson, a coach whose groundbreaking triple option offense led him to two Division 1-AA National Championships at Georgia Southern. Johnson inherited a Navy team that was winless during the previous season and had only a total of three winning campaigns since 1982.

The service academies had traditionally been dominant football powers in the years prior to the Second World War, but the emergence of the NFL as a lucrative industry diminished their relevance. While some excellent professional players suited up for the academies in the modern era (most notably Super Bowl winning quarterback Roger Staubach of Navy from 1961-64), many elite athletes are dissuaded from committing to the academies due to the required four years of military service upon graduation.

Any athlete who commits to Army, Navy or Air Force does so with the understanding that they must delay a potential NFL career for at least four of their prime playing years. Playing and representing your nation on the football field and in the armed forces is certainly a great honor, but it is also an act of individual sacrifice for an elite NFL caliber talent.

Fielding a roster of players who will go onto serve their nation as military officers is a uniquely rewarding but challenging responsibility. Coaches must figure out how to make these teams greater than the sum of their collective parts, as they tend to field very few players that have star professional football careers in their future.

Since 2002, the Navy Midshipmen have sustained a period of excellence that few thought would be attainable for service academies at the Division I level. The triple option is the perfect scheme for a roster like Navy; Very few college teams run an entirely option based offense, so it is hard to plan against and often catches opponents off guard. Each and every play has a multitude of outcomes. The quarterback can keep it on the draw, pitch it outside to his back or receiver or hand it up the middle to his barreling fullback. While Navy does not throw the ball often, when they do go to the air, they throw it deep and with success.

Under Johnson and his successor Ken Niumatalolo, the Midshipmen have tallied eight or more wins in 12 of the last 13 seasons, and consistently rank in the top five in total yards rushing per game. The Navy program ascended to new heights in 2015, when they went 11-2 and finished tied for first in the American Athletic Conference, finishing the year ranked 18th in the Associated Press Top 25.

This season, Navy sits at 4-1, including the incredible upset of No. six Houston this past weekend. The Midshipmen outlasted the Washington State Cougars in a 46-40 contest in which they tallied over three hundred yards on the ground and forced three turnovers on defense.

The win was Navy’s first over a top-10 opponent since 1984, and perhaps their most important victory since upsetting the Notre Dame Fighting Irish 46-44 in 2007.

An American Athletic Championship is attainable for this team, as is a spot in a coveted New Year’s Day Bowl Game. Navy will also go for their 15th straight victory against Army in the final game of the College Football regular season on Dec. 10, and this “Good Luck Charm” plans on being there to witness it.