Scientists working at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University recently uncovered a possible new cure for HIV-positive patients that involves a specialized gene editing system, which has safely eliminated the virus from the DNA of human cells grown in culture.

The study, published online in the journal Scientific Reports, was headed by Kamel Khalili, Laura H. Carnell Professor and Chair of the Department of Neuroscience, Director of the Center for Neurovirology and Director of the Comprehensive NeuroAIDS Center at Temple University.

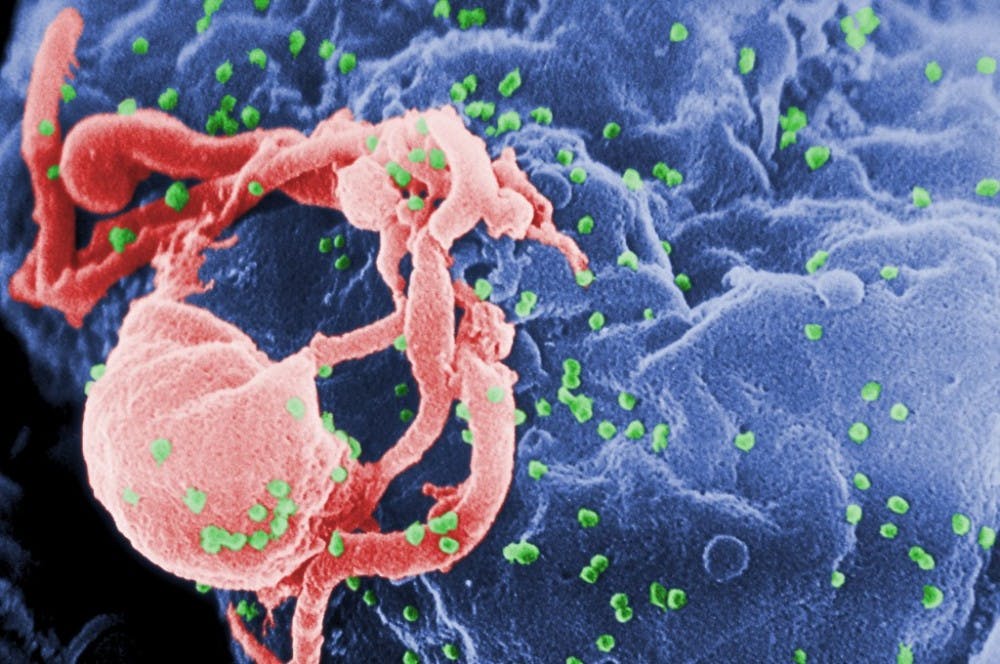

HIV stands for human immunodeficiency virus. Untreated HIV can eventually lead to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Thus far, there is no method to completely rid the human body of HIV once one acquires the virus. HIV specifically attacks the body’s immune system and the CD4 cells (T cells) that help the immune system fight off infections. HIV can reduce the number of CD4 cells, which makes a patient more likely to get infections or infection-related cancers.

Since it was first discovered in the 1980s, HIV/AIDS has resulted in more than 25 million deaths, and curing this disease has been the primary goal of thousands of researchers across the globe.

The current treatment for controlling HIV infection involves the consumption of antiretroviral drugs. If antiretroviral drugs are taken the right way, every day, these medicines can dramatically prolong HIV-positive patients’ lives. However, patients on antiretroviral therapy who stop taking the drugs experience a rebound in the replication of HIV; Thus, the treatment is not sustainable. Eventually, the presence of numerous copies of HIV will weaken the immune system and cause AIDS.

“Antiretroviral drugs are very good at controlling HIV infection. But patients on antiretroviral therapy who stop taking the drugs suffer a rapid rebound in HIV replication,” Khalili said in a press release.

Though HIV research has focused primarily on the treatment rather than the elimination of the virus, recently there has been a drive to stimulate a robust immune response that could remove the virus from cells. Thus far, none of these approaches has worked.

Dr. Kalili’s team has tried a different strategy: targeting HIV-1 proviral DNA using gene editing. More specifically, the team worked with a system that locates the HIV-1 DNA in the T cell genome, and a nuclease enzyme that can cut strands of T cell DNA. The nuclease is used to edit out the HIV-1 DNA sequence, and the loose ends of the genome are subsequently recombined by the DNA repair machinery in the cell.

In their most recent study, Dr. Kalili and colleagues proved that the technology can not only eliminate the virus from cells but can also protect cells against reinfections and reduce the viral load in patients’ cells.

Another part of their study examines off-target effects and toxicity. Utilizing the ultra-deep-whole-genome sequencing mechanism, the researchers were able to analyze the specific genomes of HIV-1-eradicated cells for gene mutations, even in genes that are outside the regions that the guide RNA targets. These studies were used to prove that the HIV-eradicated cells could function normally.

“The findings are important on multiple levels,” Dr. Khalili said. “They demonstrate the effectiveness of our gene editing system in eliminating HIV from the DNA of CD4 T cells and, by introducing mutations into the viral genome, permanently inactivating its replication. Further, they show that the system can protect cells from reinfection and that the technology is safe for the cells, with no toxic effects.”

“These experiments had not been performed previously to this extent,” he added. “But the questions they address are critical, and the results allow us to move ahead with this technology.”