See part 1 of this series here.

With tuition rising, students often complain that Hopkins costs too much, and the University should use its billions to reduce their financial burden instead of erecting yet another shiny building.

Students ask where their dollars go, often expressing anger toward the lack of transparency surrounding the use of their tuition money. The University has never made this information easily available.

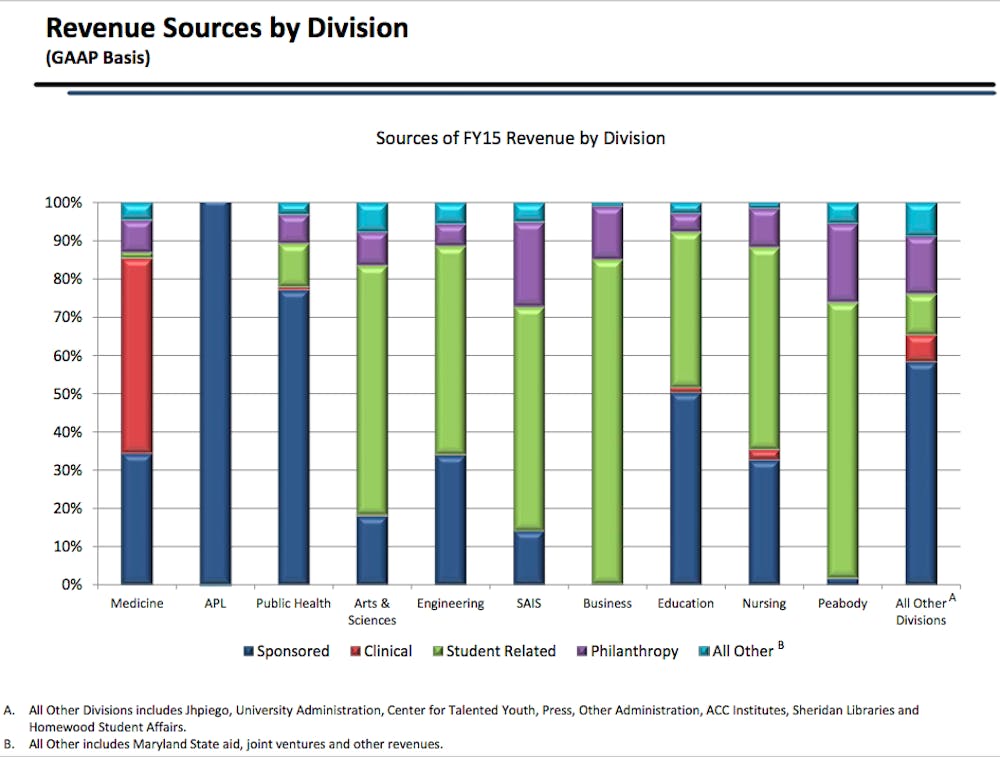

In reality, the majority of the University’s endowment and revenue belongs to the many schools not found on the Homewood campus. The two Homewood schools run much leaner than Hopkins’ reported endowment would suggest.

In 2015, the University’s endowment was roughly $3.4 billion with the Whiting School of Engineering (WSE) and the Krieger School of Arts & Sciences (KSAS) owning about 18.5 percent in total.

According to James Aumiller, the senior associate dean of finance and administration for WSE, $130 million of the University’s reported endowment belongs to WSE. His counterpart in KSAS, Daniel A. Cronin, cites a $500 million endowment. The remaining 81.5 percent of the University’s endowment belongs to the other schools such as the School of Medicine and the Carey School of Business.

Aumiller explained that looking at the total endowment does not reflect the money available to KSAS or WSE, which help to fund other Homewood Campus programs, such as the Sheridan Libraries, Campus Safety and Security and Homewood Student Affairs.

“When I read the national papers, and they got Hopkins raising $3.4 billion, that’s not going to the Krieger or Whiting schools,” Aumiller said. “A big hunk of that is the School of Medicine and grateful patients.”

Other top ten universities have endowments that are up to ten times the size of that of Hopkins. Harvard’s endowment in 2014 was $36.4 billion, while Yale reported $23.9 billion. Harvard can use endowment funds to subsidise other schools, since more of their endowment is collected centrally and disseminated among the schools. Roughly 30 percent of Harvard’s endowment does not belong to a specific school. Harvard can therefore unilaterally use such funds to subsidise any school. The Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences, for example, pays for 50 percent of its budget through endowment funding. For KSAS and WSE, the number hovers between five and seven percent.

Hopkins receives restricted and unrestricted gifts, but most are first given to a specific school or department. Usually, donations are not collected centrally. Both KSAS and WSE employ a team of development officers who do the majority of fundraising for each school. The schools then accept the donations and put them into separate funds.

“It’s put into a separate set of funds, and we basically get what we call the ‘spendable income.’ You can think of it as a dividend or interest payment that is available to spend. They are invested in a series of funds that a family or an individual decide to give money for,” Cronin said.

Difficulties can sometimes arise when an endowed gift has too many restrictive stipulations. These restrictions can make it difficult for Aumiller and Cronin to find faculty, students or programs to support using these gifts.

Associate Vice Provost for Development and Alumni Relations Rob Spiller and his colleagues in each school play a crucial role in helping to keep funds flexible.

“Our job really is to try to discuss with potential donors the need for unrestricted and flexible support, but we also work with the donors where we can to direct their support to areas that are important to them and that they care about,” Spiller said. “We are... the translator between what the donor wants to achieve and what the needs of the University, or schools, are. It’s a negotiation in many cases — especially at the higher level gifts — about how we can accomplish their desires, their objectives and the needs of the schools.”

Spiller formerly worked at Yale, a school that collects money centrally before distributing it.

“Yale is structured a little bit differently, where more money is raised in the center. But, here it’s very decentralized in that sense,” Spiller said. “Proportionally we raise a lot of money from the School of Medicine and through the hospital. Yale tends to get a higher proportion of their gifts from their alumni.”

The University’s decentralized financial structure is the reason why $630 million of the University’s $3.4 billion endowment belongs to the Homewood schools. At Hopkins, each school must fund itself. For the most part, schools do not share revenue or philanthropic funding. KSAS and WSE are exceptions. They share a portion of their respective revenues due to their shared resources, student body and proximity.

“The endowment is the key for most of the universities that we’re competing against, and that’s what sets us apart. The other piece that sets us apart, at least as an arts and sciences school, is that we have a model [where] all tuition for arts and sciences comes into arts and sciences. We have to cover all of our bills with what we bring in. Most of the other arts and sciences schools are usually subsidized significantly by business schools, law schools, other schools that tend to bring in more revenue,” Cronin said.

The most recent budget for KSAS totaled $350 million, while WSE totaled $220 million.

Aumiller compared Hopkins to universities like the University of Maryland that centralize their revenue.

“Hopkins is a very bottom-up institution. [For] a lot of schools, like Maryland and others, the provost controls all of the revenue. All of the revenue goes to the president and the provost, and then we would have to go to them and say, ‘We need $150 million to run my school’ and then justify it,” he said.

The downside to this structure is that the Homewood schools cannot tap into the revenues of more profitable schools. The University’s decentralization, however, does allow each school more flexibility and autonomy.

“At least at Hopkins we have the flexibility of being our own creative sources of generating other revenues at the bottom and getting to keep a lot of that money to be able to use in a very fungible way,” Aumiller said. “If this year we wanted to put an emphasis on undergraduate research laboratories and fix them up, then we could make that decision.”

With philanthropy comprising roughly five or seven percent of each school’s budget, tuition is important to supporting the schools. Thirty-five percent of WSE’s revenue comes from undergraduate tuition dollars, 12 percent from JHU-EP (Engineering for Professionals) or part-time Master’s students, nine percent from Ph.D. tuition, nine percent from full-time Master’s students, 30 percent from research and five percent from philanthropy.

In KSAS, Cronin cites similar numbers: 52 percent undergraduate tuition, 13 percent Ph.D. tuition, 10 percent from Advanced Academic Programs/Masters, 18 percent research and seven percent philanthropy. Comparatively, 23 percent of Harvard’s arts and sciences school’s budget comes from tuition.

Undergraduate tuition mostly funds programs that service students, Aumiller says. With 65 percent or more of Whiting’s and Krieger’s budget relying on undergraduate and graduate tuition, the tuition rate is crucial to each school.

“What’s the tuition rate going to be for the next year? That’s a conversation between the president, the provosts, the deans, us,” Aumiller said.

Cronin stressed that affordability and understanding the price the market can bear are both important to setting the tuition rate.

“When we look at our peer institutions, the piece that makes it really hard and challenging for us is that we have a much lower endowment than the people we typically compete against,” he said. “There are some institutions that we compare to that literally would not have to charge a dime of tuition and could run their entire operation if they chose to.”

Sponsored research also comprises another major segment of each school’s budget. Cronin disclosed that research in KSAS mostly pays for itself.

“The research dollars that come in pay for research. If we didn’t have the dollars then we wouldn’t be spending that amount of money,” he said.

Even though tuition and research fund the majority of the budget, philanthropy plays a crucial role to help the school do more than stay solvent.

Ed Schlesinger, Benjamin T. Rome Dean of the WSE, echoed Cronin’s sentiment.

“This is a very lean university, in terms of the way it runs,” he said. “When it comes to financial aid and scholarships, we are highly dependent on our alumni supporters, and a lot of students on this campus...are benefiting from the support we get from our alums.”