Angela Davis, internationally recognized activist, writer and scholar, spoke to a sold-out Shriver Hall on Tuesday as part of the JHU Forums on Race in America speaker series. She spoke about the black radical movement, the need to dismantle the prison industrial complex and the importance of fighting for social justice.

Davis championed social and political rights as a young woman in Birmingham, Ala. and after college in the 1960s as a member of the Black Panther Party. In 1969, Davis gained national attention when UCLA, under orders of then-governor of California, Ronald Reagan, tried to fire her from her teaching position because of her ties to the Communist Party USA. In 1970, Davis was put on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted List and imprisoned for 16 months on wrongful charges.

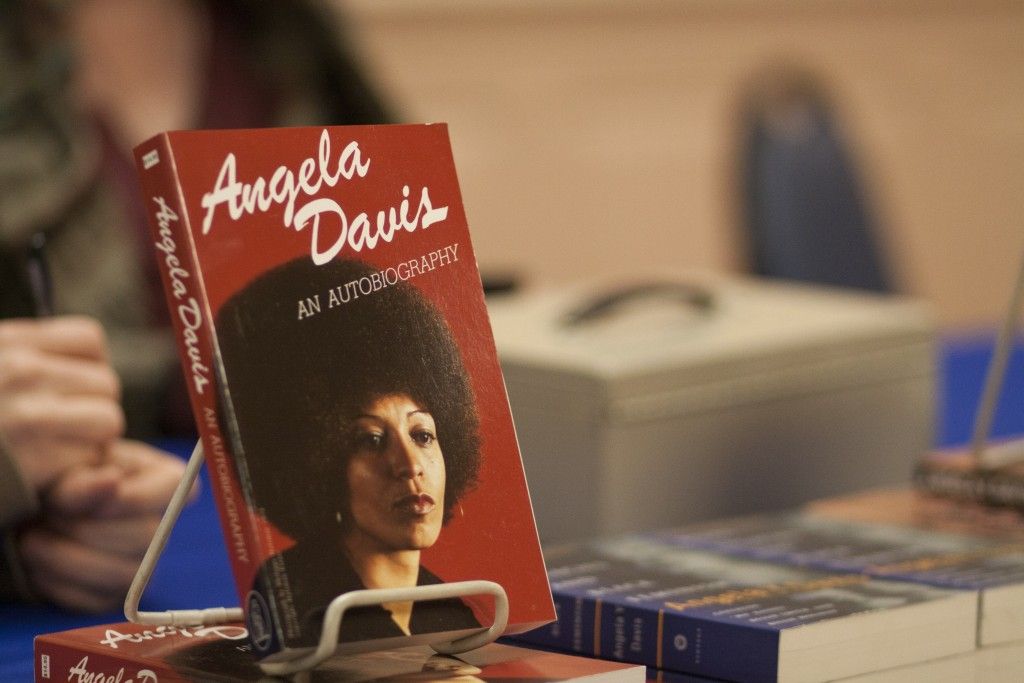

Protesters around the world led the “Free Angela Davis” movement during her incarceration. She was eventually acquitted by an all-white jury in 1972. She is now a distinguished professor emerita at multiple universities, author of nine books and a frequent speaker around the world.

Davis was introduced by Provost Robert C. Lieberman and Associate Professor of Sociology Katrina Bell McDonald.

Davis’ appearance was met with a standing ovation. She began her talk by discussing past events in the city of Baltimore, most notably the recent death of Freddie Gray, the following protests, the efforts to achieve justice for him and the fight to persuade the world that “Black Lives Matter.”

“The question these and other efforts have raised is whether it is possible to purge policing apparatuses of [racism]... simply by holding individual officers accountable,” Davis said. “How can individuals be held accountable without concealing the deep, structural racism that is embedded in the very system of policing and imprisonment? That is the overarching question I want to address this evening.”

Davis revealed that although the United States makes up only five percent of the world’s population, the nation constitutes 25 percent of the world’s imprisoned population. She further stated that one-third of the world’s incarcerated women reside in U.S. jails. Today, approximately two million Americans are in prison and seven million are under correctional control.

“The United States of America is a prison nation,” she said.

Davis explained that while many recognize the problem of over-incarceration, current solutions do not address the full complexities of this problem.

“The dominant tendency has been to provide solutions that attempt to reduce these massive numbers — that is to say, a quantitative solution,” Davis said. “And I don’t want to minimize how important it would be to reduce the number of people behind bars... What we call ‘de-carceration’ is a key strategy of abolitionist approach... But de-carceration by itself would be no guarantee that the use of punitive measure, police and prison, to solve deeply ingrained social and economic problems, would not continue. And so, an abolitionist approach invites us to attempt to imagine and devise more effective solutions, not stop gap measures.”

The abolitionist approach that Davis mentioned calls upon the long history of black freedom movements during the fight against slavery and the Civil Rights movement to resist oppression. 21st century abolitionism deals with a new challenge: the prison industrial complex. Davis says that the prison industrial complex has led to mass incarceration, a so-called police state and the production of poverty, injustice and racism. Davis argued that prisons, armed police forces and capital punishment are not necessary features of our society.

“The point that I’m trying to make is that these technologies of punishment should be considered impermanent,” she said. “They haven’t always existed. And [if that’s true] then they don’t have to exist in the future.”

Davis took issue with the death penalty in particular for its inhumanity, characterizing it as obscene.

“The fact that the death penalty persists can only be explained by the persistence of the structures of slavery,” Davis said. “We still live with the structures of slavery. The death penalty would have been abolished at the advent of what was called democracy in this country, had it not been retained in southern slave law.”

Davis concluded her talk by connecting the black radical movement to movements that resist oppression of all forms.

“The struggle against prisons is an abolition movement... Radical struggles for black freedom have never been exclusive,” she said. “They have always been linked to struggles for Native American sovereignty, against racism, no matter who the target, in solidarity with working people of all racial and ethnic backgrounds. It has been a struggle against capitalism, and therefore the struggle for black freedom is a struggle for radical democracy.”

In the question and answer session, one audience member asked where individuals should start in addressing the issues outlined in Davis’ talk.

“Start everywhere,” she said. “This means that everyone has the opportunity to participate in the creation of new movements that can hopefully and eventually bring an end to the prison industrial complex.”

Several audience members asked Davis for her opinion on Maryland’s investment in jails, specifically referring to Governor Larry Hogan’s recent decision to spend $480 million on a new Baltimore city jail complex. Davis said that the money could be better used by re-envisioning education and building new schools. She cited the example of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors’ refusal to finance a new jail for their city, which she said demonstrates their view that the money would be better invested in education or healthcare rather than incarceration.

BSU Vice President Tiffany Onyejiaka asked Davis what can be done about the problems prescribed in the “pre-school to prison” pipeline. This framework proposes that inner-city schools, through poor-quality equation and penal punishments for minor infractions, are preparing their students for a life in prison. In response, Davis said that people need to work with educators and adults and engage in work that will disarticulate certain notions, such as the link between black males and prisons.

“I think her talk was very important in telling people how complex racism is and how you can’t tackle it from one angle; It has to be tackled from all angles,” Onyejiaka said. “I felt the questions were [ones] that many people had, and she gave answers that were very important. One of the questions I felt was highly inappropriate, but I was glad it was asked... A lot of people think they can only [support] the feminist movement, the Civil Rights movement, the gay rights movement — they don’t understand that to be for justice and equality is to be for justice and equality for all.”

The “highly inappropriate” question Onyejiaka mentioned was asked by a young man who believed that the feminist movement’s association with the black radical movement had led to the feminization of black men. He was concerned that this feminization made black men less attractive to black women.

“Does [the feminization of black men] not threaten the reproduction of black radicals?” he asked.

In response, Davis asserted that feminism has been key to the development of the black radical movement, citing the important contributions of women during the Civil Rights movement, especially their role in orchestrating the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Davis stressed that feminism is a movement for everyone, not just women.

“I’ll begin by saying that so much damage has been done to our movement by the assumption that men are the human beings that really matter,” she said. “I can remember when I was a young activist, [we said] black liberation, but what does that mean? That means liberation of the black man. And we didn’t even realize that we weren’t even standing up for ourselves... So, feminism is an approach everyone can benefit from, regardless of gender, regardless of race.”

Freshman Karima Kallon was inspired by Davis’ support for young activists.

“I thought it was really inspiring, and it was really cool seeing this otherworldly figure come and speak to us,” Kallon said. “She’s a great model for everything we’re trying to do in this current day and time.”

Local high school student Dabeon Brown was similarly inspired and gained knowledge that she planned on sharing with others.

“Being a young black-tivist myself, I learned a lot from her, especially about how black women are a double minority,” Brown said. “I would like to go and talk about what I just learned to people who don’t really know [about these issues].”

Senior Busola Obitayo learned about Davis in an Intersession course about mass incarceration and thought Davis was a brilliant and clear speaker.

“Sometimes as a student at Hopkins, you feel like you can’t really do anything,” Obitago said. “But now I feel that I can do something in the future to make a change.”