But when is the Libertarian debate? What are the polling numbers for the Green Party or Constitution Party? When will third party candidates have the opportunity to introduce themselves to a national audience and promote their views?

The answer? They won’t.

There is a systemic bias in the American political system against minority parties. What the established parties likely consider formalities — such as getting their candidates listed on the ballot — can pose tremendous obstacles.

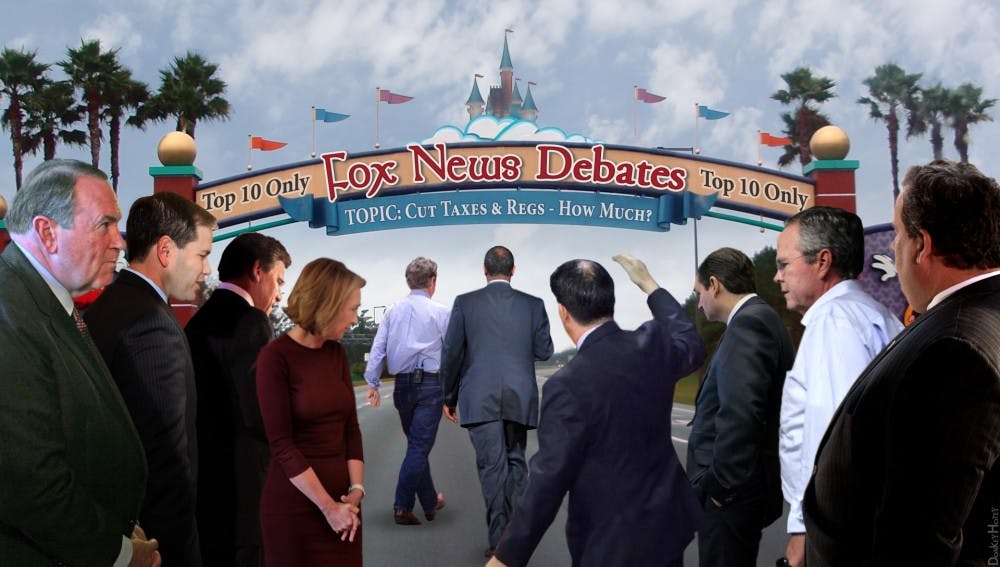

Debates are another area where third parties get shafted. Their primary debates don’t garner enough media attention to be aired on major networks, and their candidates are deliberately excluded from multiparty debates during the general election.

Furthermore, current campaign finance laws stack the odds against candidates who don’t have the benefit of either huge personal wealth or a rich, party fundraising machine. Third parties regularly get pushed aside by the two major parties, to the detriment of the whole political system.

Current ballot access rules pose the most immediate problem for third party candidates. These are the state-by-state regulations about what candidates must do to have their names appear on the ballot on Election Day.

Petition requirements, a common component, are often very high. Oklahoma, for example, requires tens of thousands of signatures. For the established parties, petitions are easily taken care of by circulating the document to the party faithful. State operations for smaller parties often do not have the time or resources to canvass enough neighborhoods to fill out the petitions.

Registration fees can also be high, relative to the amount of money in a given third party’s coffers. Together, the Democrats and Republicans are able to exclude Libertarians, Greens and others with ease. The last time any third party candidate made it onto the ballot in all 50 states was in 2000, when Pat Buchanan rode the coattails of Ross Perot’s success with the Reform Party. It’s hard to win an election when you’re not even on the ballot.

The exclusion of third parties from televised debates also prevents unorthodox candidates from connecting with voters. The chance to educate people about alternative ideologies is an invaluable tool in diversifying elections, yet from media coverage you’d think there were only two opinions on any given issue.

Debate organizers justify the segregation by claiming that any candidate is welcome in the debate provided they meet a polling threshold, but the polls that are used to judge only include establishment candidates. You get 0 percent approval ratings in polls you’re not included in. As with ballot access rules, third parties are marginalized.

The biggest hurdle third parties face is, unsurprisingly, fundraising. The Democrats and Republicans have huge donor networks, as well as a legion of super PACs ready to give millions of dollars. Basic campaign costs, such as yard signs, flyers and ballot registration fees, can eat into the tiny budgets available to smaller parties. Ross Perot had his own personal fortune to draw upon; more recent candidates don’t have that luxury.

Pricier advertising strategies like TV ads are even further beyond the reach of cash-strapped campaigns. Their limited funding translates to limited voter outreach and even fewer people invested in their candidates and their platforms.

It is unfair of the major parties to exclude alternative political parties from the media, debates and ultimately elections. The Democrats and Republicans have maintained a duopoly over the political “market.” It has stifled competition just as surely as duopoly in any economic market.

Amending ballot access regulations to be more equitable would allow more people to vote for candidates who truly represent their views, rather than just a lesser of two evils.

More inclusive polling and debates would produce a more robust discussion of policy ideas. Moreover, it would introduce Americans to a wider variety of ideas about politics and the proper role of government.

Finally, campaign finance reform needs to reduce the amount of money in politics, specifically through limits on spending rather than donating. Spending limits would even the playing field and grant a larger degree of freedom to third parties.

Some of these reforms are easier to achieve than others. Comprehensive campaign finance reform is likely far in the future.

More inclusive debates, on the other hand, might be a reality sooner. Libertarian and Green party candidates from 2012 are involved in a lawsuit against the Commission on Presidential Debates. They allege that the current system violates anti-trust laws, a novel approach that, if it works, will break the Democrat-Republican duopoly. One can only hope.