By PAIGE FRANK For The News-Letter

One of the mysteries of paleontology is the exact starting point of the Age of Mammals, when the death of the dinosaurs allowed mammalian life to diversify and take over the planet.

Earlier this month, though, the line grew a little clearer when scientists from the Autonomous University of Madrid, University of Bonn and the University of Chicago published the results of a new fossil discovery in Spain.

The discovery of the new organism, Spinolestes xenarthrosus, officially moves the previous record of preserved mammalian structures back 60 million years earlier than was previously thought. It places the existence of mammals on Earth during the age of the dinosaurs, over 125 million years ago.

Scientists were able to identify preserved soft tissue from the fossil, including the liver, lung and diaphragm. They were also able to discern finer details such as intact guard hairs, underfur and hedgehog-like spines.

Several of the anatomical structures preserved in the fossil are the first or earliest of their kind.

The Spinolestes fossil revealed evidence of a large external ear, the earliest-known example in the mammalian fossil record. In fact, the fossil was so well-preserved that scientists were able to identify a fungal hair infection the creature possessed.

“With the complex structural features and variation identified in this fossil, we now have conclusive evidence that many fundamental mammalian characteristics were already well-established some 125 million years, in the age of dinosaurs,” Zhe-Xi Luo, a co-author of the published Spinolestes study, said in a statement from the University of Chicago.

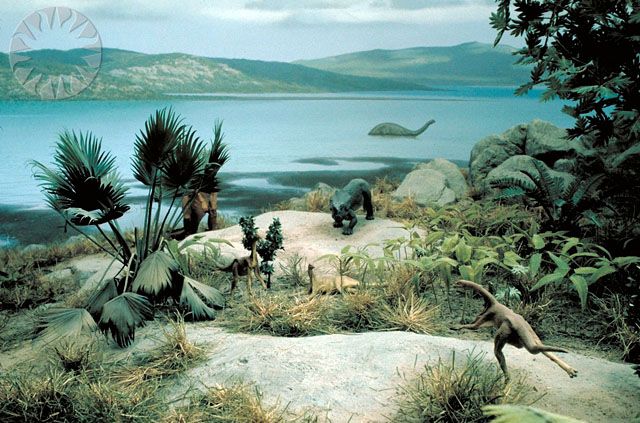

Spinolestes existed during the Cretaceous period in a wetland area of Spain. In terms of its skeleton, the creature is similar to the modern day armadillo, although closer in size to a juvenile rat. The fossil itself was measured to be 24 centimeters long, and the creature was estimated to weigh between 50 to 70 grams, about the weight of a tennis ball.

Extra joints between Spinolestes vertebrae mimic those of the armadillo, suggesting the animal’s lifestyle might have been similar as well. From the organism’s skeletal features, scientists also inferred Spinolestes was a ground dweller that fed on insects.

Besides providing suggestions about theorganism’s build and lifestyle, the fossil marks the first discovery with preserved soft tissue of the chest and abdominal cavities of a Mesozoic animal.

Spinolestes’s organs were preserved through a process called phosphatic fossilization, leaving detailed microscopic structures such as the bronchiole structure of the lung or iron residue of the liver visible.

Scientists also note a curved muscular boundary dividing the chest and abdominal cavities that was most likely a diaphragm for respiration.

The organs of Spinolestes are now the earliest known record of mammalian organ systems.

Perhaps the most unique feature of the Spinolestes fossil, however, was the integumentary structures preserved.

“This Cretaceous furball displays the entire structural diversity of modern mammalian skin and hairs,” Luo said.

A train of small spines also runs down the mammal’s back, similar in structure to that of a hedgehog. The spines are known as dermal scutes, plate-like structures made of skin keratin.

These scutes are another trait linking Spinolestes to the modern armadillo. Besides the dermal scutes, individual hair follicles and bulbs were preserved in the fossil.

Using electron scanning, scientists were able to identify the composition of the individual hair shafts.

What they discovered was a compound follicle structure in which multiple hairs emerge from the same pore. It was from abnormally truncated hairs that scientists inferred the fossil possessed a fungal skin infection.

“Hairs and hair-related integumentary structures are fundamental to the livelihood of mammals, and this fossil shows that an ancestral long-extinct lineage had grown these structures in exactly the same way that modern mammals do,” Luo said. “Spinolestes gives us a spectacular revelation about this central aspect of mammalian biology.”