By MANISH PARANJPE Staff Writer

The symptoms of schizophrenia — auditory and visual hallucinations, delusions and irritability — have long been known. Yet the underlying causes of this disease, which affects more than one in 100 Americans, are still a mystery. However, a new study published in The American Journal of Psychiatry, found that microglial-based inflammation may also play a role in the development of schizophrenia. Inflammation in the brain caused by the microglia, or the defense cells of the nervous system, has long been observed in schizophrenic patients. Post-mortem studies have revealed large structural abnormalities in the complex architecture of the brain in individuals with schizophrenia.

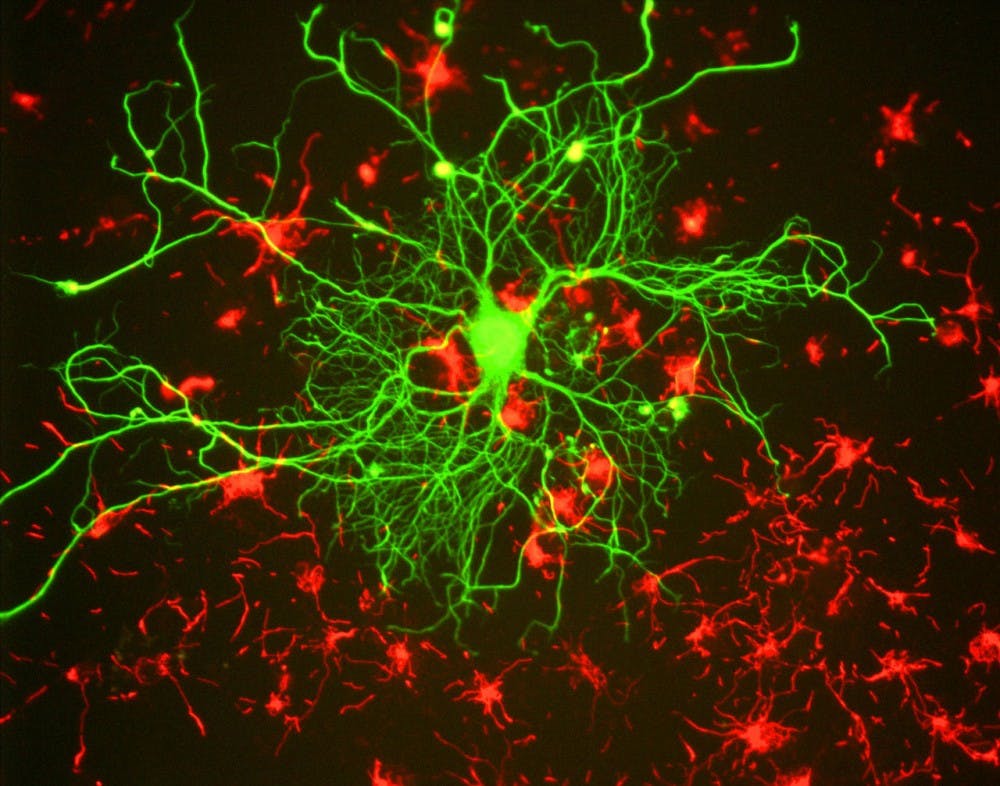

The field of neuroscience has long centered on the study of neurons, the fundamental units of the nervous system that are responsible for transmitting electrical signals throughout the body.

Until recently, research has largely ignored the role of glial cells, which are thought to occupy about half the volume of the brain.

Microglia are a type of glial cell that specializes in mounting immune responses to protect the nervous system, including pruning away damaged neurons. After being activated by mechanisms that are still not fully understood, microglia can engulf damaged neurons, often releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines in the process.

Inflammation caused by microglial cells has been well-characterized in a host of diseases, including autism, Alzheimer’s disease and now schizophrenia. Studying the role of microglia in schizophrenia could help uncover the precise molecular changes that lead to schizophrenia. This, in turn, may enable scientists to engage in early intervention, stopping the disease even before its onset.

Researchers at North Carolina State University and Imperial College London analyzed microglial activity amongst individuals predicted to be at an ultra-high risk for schizophrenia and those already diagnosed with the disease.

By using [11C]PBR28, a radioactive tracer that binds to the microglial translocator protein (TSPO), the researchers were able accurately to detect the activity of microglial cells. Microglial activity was compared to normal individuals as controls.

In this study, lead author Peter Bloomfield and his colleagues found that a greater volume of a radioactive tracer was present in the total gray matter, frontal lobe and temporal lobe regions of those in the ultra-high risk cohort, but a lower volume was found in these individuals’ cerebellum and white matter.

Even after correcting for variations in the binding affinity of the tracer in their test individuals, the researchers still found increased microglial activity in the high-risk patients. Similar results were observed when sci