By REGINA PALATINI

The New Horizons Spacecraft, which was designed, built and operated by the Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, became the first space probe to fly past Pluto on July 14, flying by at about 7,750 miles above the surface. After beginning its journey on Jan. 19, 2006 at Cape Canaveral, Fla., New Horizons has journeyed almost three billion miles in nine and a half years, averaging a blistering 36,373 miles per hour.

The spacecraft itself is fairly small, about the size of a grand piano, and weighing in at about 1,040 pounds. New Horizons began its journey in style, establishing its first record by being launched at 36,000 miles per hour, which is the fastest launch speed ever recorded. As it continued its landmark journey, New Horizons slowly lost speed and its flyby speed became a slightly slower 30,000 miles per hour.

Launch timing was critical for the space probe to be able to take advantage of the gravitational pull of Jupiter. Flying past the planet allowed the probe to gain speed in a maneuver known as a “gravity assist.” It was drawn into Jupiter’s gravitational field, gained almost 9,000 miles per hour and then escaped, moving onward toward Pluto.

Interestingly, New Horizons spent about two-thirds of various periods of its journey in hibernation. This was designed to reduce wear on most of the probe’s electronic components. Its final wake-up call came on Sunday, December 7, 2014, when it was about 162 million miles from Pluto.

New Horizons holds a wide array of scientific instruments with interesting names. “Ralph” consists of a visible and infrared imager/spectrometer and provides color, composition and thermal maps. “Alice” is an ultraviolet imaging spectrometer, which analyzes the composition and structure of Pluto’s atmosphere. The Venetia Burney Student Dust Counter or “VBSDC” was built and operated by students at the University of Colorado and measures the space dust that hits New Horizons during its voyage across the solar system.

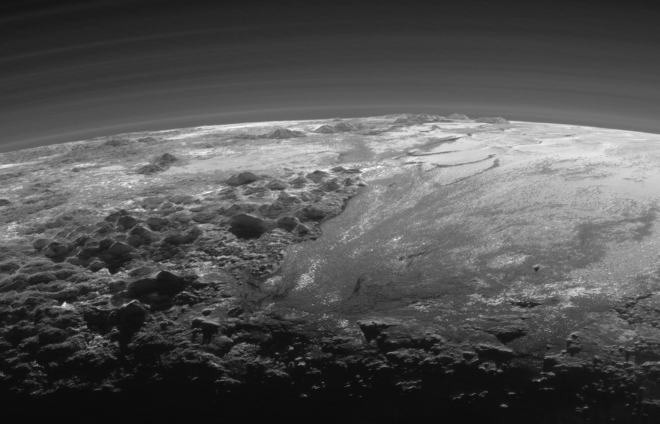

“Pluto is showing us a diversity of landforms and complexity of processes that rival anything we’ve seen in our solar system,” New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., said in a NASA statement. “If an artist had painted this Pluto before our flyby, I probably would have called it over the top — but that’s what is actually there.”

The downloading of the massive amounts of information New Horizons is receiving about Pluto will take about a year, with the best resolution ranging around 440 yards per pixel. Images so far reveal features suggestive of valleys, dunes and nitrogen ice flows on the planet. Mountainous regions have also been observed. Sensors on New Horizons have reported a thin nitrogenous atmosphere, and other data suggests different regions of frozen methane and nitrogen.

The New Horizons Spacecraft is now more than three billion miles from Earth and more than 43 million miles past Pluto. It continues to operate as designed. With approval from NASA, New Horizons will continue on toward the Kuiper Belt, which lies beyond Pluto.

New Horizons is part of NASA’s New Frontiers program, which aims to explore more distant planets in the solar system such as Jupiter and Venus. Another New Frontiers mission is Juno, which was launched in August 2011. Juno is en route to Jupiter and will arrive there in 2016.

Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto only 85 years ago. Tombaugh, a farmer’s son from Kansas, made his observation using a telescope in Flagstaff, Ariz. Before his death one of his last wishes was that his ashes be sent to space. NASA fulfilled his wish by including a small container with his remains on the probe.

An inscription on the container reads: “Interred herein are remains of Clyde W. Tombaugh, discoverer of Pluto and the solar system’s ‘third zone,’ Adelle and Muron’s boy, Patricia’s husband, Annette and Alden’s father, astronomer, teacher, punster, and friend: Clyde W. Tombaugh (1906-1997).”