The big chemistry test is tomorrow. You’ve been up pouring through and highlighting your textbook, consolidating your notes into one dense study sheet, and cramming all the information about alkanes, aromatic molecules and reaction mechanisms that you can in one night. Your brain is sated, and it’s time for a celebratory cup of coffee to cement those facts.

Researchers have found that your performance on the test is not affected as much by the late-night cramming but by a different set of chemical and neurological connections — those facilitated by sleep.

Though the relationship between memory performance and sleep has long been known by scientists, the exact mechanism has remained elusive. Paula Heynes and Bethany Christmann, graduate students in the Department of Biology at the National Center for Behavioral Genomics at Brandeis University, have made progress toward realizing this relationship through their research into memory neurons and sleep. Their work emphasizes just how important sleep is in forming lasting memories.

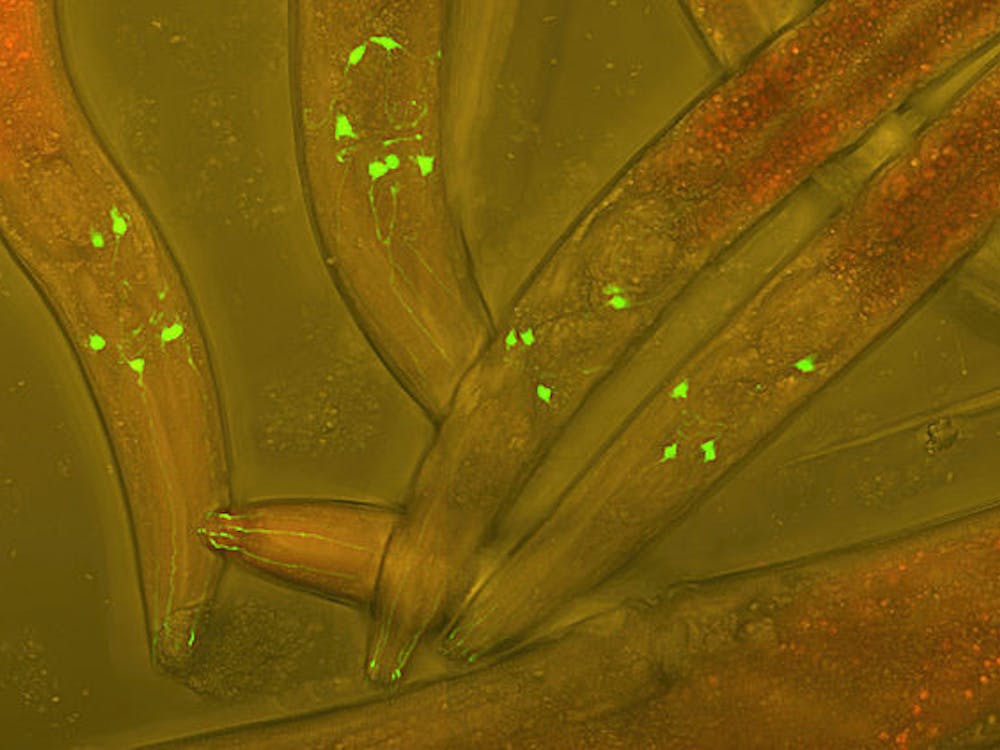

Heynes’s and Christmann’s research, which they performed on Drosophila melanogaster flies, concluded that the neurons necessary for memory consolidation are in fact sleep-promoting neurons.

To discover this, Heynes and Christmann activated the neurons necessary for memory consolidation of flies. These neurons are in an area of the Drosophila brain called the mushroom body, which is where memories are stored. They activated the neurons by increasing the temperature of dTrpA1, an ion channel, which caused it to depolarize and open the neuron channels, thus activating them.

The researchers noticed that such activation caused a dramatic increase in the amount of sleep that the flies experienced. It did not, however, affect the locomotion of the flies. They functioned normally when wakened, exhibiting normal flying behaviors immediately, but fell back asleep significantly more quickly, too.

In short, the researchers discovered a surprising relationship between sleep and memory. The process of consolidating memories and converting short-term to long-term memory in the brain is what in fact causes it to desire sleep so much. So that’s why intense hours of studying chemistry are such a potent soporific!

The work that Heynes and Christmann did has important implications for other work in neuroscience. Their findings elucidate the roles of specific neuronal pathways in the brain and thus impart a greater understanding of brain chemistry to the science community.

Their research also has promising applications to humans: Understanding the relationship between sleep and memory in flies is a step toward understanding it in humans. And knowledge of the neuronal pathways of sleep and memory in humans is ultimately the key to solving disorders in sleep and memory, such as insomnia, REM behavior disorder and even Alzheimers and Parkinson’s disease.

The role of sleep in memory consolidation is a problem that has vexed students and researchers alike. But it is a problem which researchers at Brandeis are, now, one step closer to solving.