Vice Provost for Research Denis Wirtz, a polymer physicist, is on the way to making one of the largest breakthroughs in pancreatic cancer research... without having taken a single formal biology class.

Wirtz grew up in Belgium. As a young adult, he saw the United States as a mecca of adventure and opportunity. Thus, upon completion of his bachelor’s in chemical engineering at the Université Libre de Bruxelles, he left the comfort of Belgian chocolate and beer to attend Stanford University. There, he narrowed in on polymer physics, receiving his Ph.D. before traveling to France to complete his post-doctorate.

It was then, knee-deep in theoretical polymer physics research, that Wirtz was invited to come to Hopkins where he decided he would like to try his hand at a different area of study — biology. Lacking any formal education in the area, Wirtz found himself learning biology by doing biology. He credits Thomas Pollard, an early mentor of his, for much of the knowledge he acquired, noting that Pollard was his “entry into biology.”

Wirtz now runs a lab entirely dedicated to biological cellular research. His lab is one of the 15 or so labs that make up the Institute for NanoBioTechnology. Occupying almost the entirety of Croft Hall, the institute itself was actually founded by Wirtz in 2006. Wirtz focuses much of his lab’s research on cancer.

Specifically, he applies physics and engineering-based approaches to the study of the metastasis, which is the spreading of cancerous cells that occurs when the cells begin to break off from a tumor or source and spread to other tissues and organs within the body.

The peculiarity of metastasis is in its seemingly arbitrary nature. While some cancerous tumors will see cells immediately begin to break off and spread throughout the body during growth, others experience only confined cell proliferation and no cellular movement or spreading.

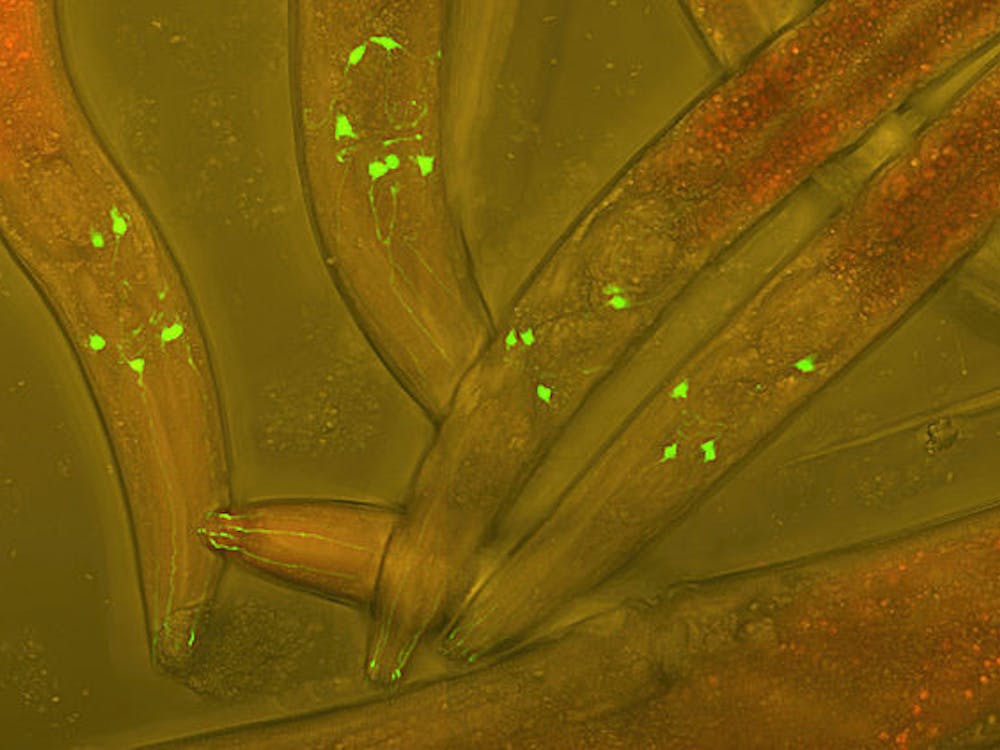

Wirtz hopes to discover just which biological factors trigger cancer cells to metastasize. His team is using everything from microfabrication to in-vivo testing to investigate methods and causes of metastasis.

“Our primary goal is to improve clinical outcomes,” he said.

Wirtz’s lab has a unique advantage when it comes to cancer research due to the proximity of the Hopkins Hospital.

Wirtz stresses just how important the collaboration between doctors or medical professionals at the hospital and Hopkins researchers is for his and countless other labs.

“We have amazing luck to have fantastic colleagues at the medical school with whom we’ve been working for many years,” Wirtz said.

These interactions not only enable researchers to get access to invaluable primary cell tissue samples but also helps guide researchers towards the study of clinically relevant problems.

While Wirtz is not one to scoff at the advancement of scientific knowledge, he says his ultimate goal is to use science to make a clinically relevant impact, such as improving therapies and treatments for diseases like cancer.

One particular colleague from the Hospital, Dr. Ralph Hruban, approached Wirtz with a rather unique puzzle to solve. Hruban asked Wirtz to look for a molecular way to identify differences in types of pancreatic cancer.

Pancreatic cancer, like most cancers, is caused by a variety of different types of mutations.

What is unique about pancreatic cancer compared to others, however, is the distinct stratification between patient cases. Patients with pancreatic cancer fall into one of two categories, long-term survivors or short-term survivors.

Thus far, attempts have been made during diagnosis to determine a method of identifying which category a patient will fall in. All of these, however, have ultimately failed. Wirtz decided to take on the challenge despite the fact that little is known about pancreatic cancer compared to other more studied types of cancer.

“The temptation if you are new to the field is to study breast cancer because so much is known... [but studying breast cancer is like] contributing a brick to the Great Wall of China as opposed to [pancreatic cancer] where every brick you lay is foundational,” Wirtz said.

The plan was to use algorithms, machine learning, imaging and other untried methods to distinguish one tumor type from the next. Although the team has been working with a limited number of samples, Wirtz ventures to say that he may have found “the dream team” of colleagues, consisting of different medical professionals such as oncologists, pathologists and surgeons collaborating with each other.

It appears that Wirtz’s claim may not be too far from the truth as he believes his team may have found the answer. The ability to predict with confidence whether a patient will be a long-term or short-term survivor could be just around the corner.

“I am an optimist, but I think we [all] are there,” Wirtz said.

The implications of such a discovery have the potential to drastically change the realm of pancreatic cancer. The prognosis for pancreatic cancer is usually death. Armed with the knowledge of approximately how long they will survive, patients would be better able to decide not only if undertaking treatment is worth it but if so how intensely.

His next steps will be to verify the initial results with more samples. Once the identification method is validated, the goal will be to apply the knowledge to the determination of therapies better targeted to the needs of each individual patient.