Eight students presented their exhibits depicting the lives of people who were enslaved on the Homewood Campus and showing how the legacy of slavery continues to affect people today. The exhibition, titled More Than a Name: Enslaved Families at Historic Homewood, included a selection of artifacts and objects and opened at the Homewood Museum on Monday.

As a part of the Museums & Society program, students helped curate the exhibition which has been in development since 2016.

Julia Rose, director and curator of Homewood Museum, and Abby Schreiber, a professor at Towson University, spoke at the opening event. Schreiber was a historian who helped coordinate the project. She said that this was the beginning of a project that is expected to continue for several years.

Schreiber hopes that the exhibit will prompt viewers to connect the past to the present.

“The projects to explore personhood provoke empathy by causing us to consider what are the similarities and differences between 19th century experiences and our own 21st century lives,” Schreiber said.

She explained that each student tried to infer as much as they could about enslaved people’s daily lives.

“Each display brings its own perspective to this,” she said. “The students have thought carefully about what makes a person.”

Some of the exhibits explored slavery specifically in Baltimore. The Carroll family, who owned the land that is now Homewood campus, bought and sold slaves in the City.

“The slave trade took place in the most central, obvious and public places in early Baltimore,” Schreiber said. “It was well documented, and the Carrolls participated in it routinely.”

She said that the exhibit offers an accurate depiction of the violence of slavery.

“The exhibit covers the material reality of the institution of slavery,” she said. “People were treated as property and treated as such through brutal physical punishment and emotional terror.”

According to Schreiber, research on black education in Baltimore City provides insight into the different opportunities and challenges that free and enslaved black people in the Chesapeake had to deal with.

“The central role of education, whether it be formal schooling, trade apprenticeship or mentorship, emerges as a critical part of the experiences of enslaved people in the region,” she said. “As more free blacks took up residence in the City after 1800, their presence changed the City’s labor markets and increased demand for education.”

While some students focused on education, others focused on stages of life, such as childhood and parenthood.

“These close studies show us that there was no typical experience,” Schreiber said.

The News-Letter interviewed four of the students who created exhibits, who explained various elements of life for enslaved people and described the process through which they conducted their research.

Sophomore Destiny Staten focused her exhibit on what life was like for enslaved children.

“I described the children and all the activities that they did and how documented and detailed their records are,” she said.

Though they were treated differently in their youth, enslaved children ultimately grew up to perform tasks delegated to enslaved adults.

“Enslaved children were just kind of kept as props, and they became workers as soon as they were physically able,” Staten said.

Staten’s exhibit included a rattle and a doll — typical children’s toys in the U.S. during the early 19th century. However, her exhibit also showed how enslaved children would not have the same access to these items as free children.

The display also noted that enslaved women would often serve as primary caretakers of the master’s children and would spend hours taking care of them at the expense of raising their own children.

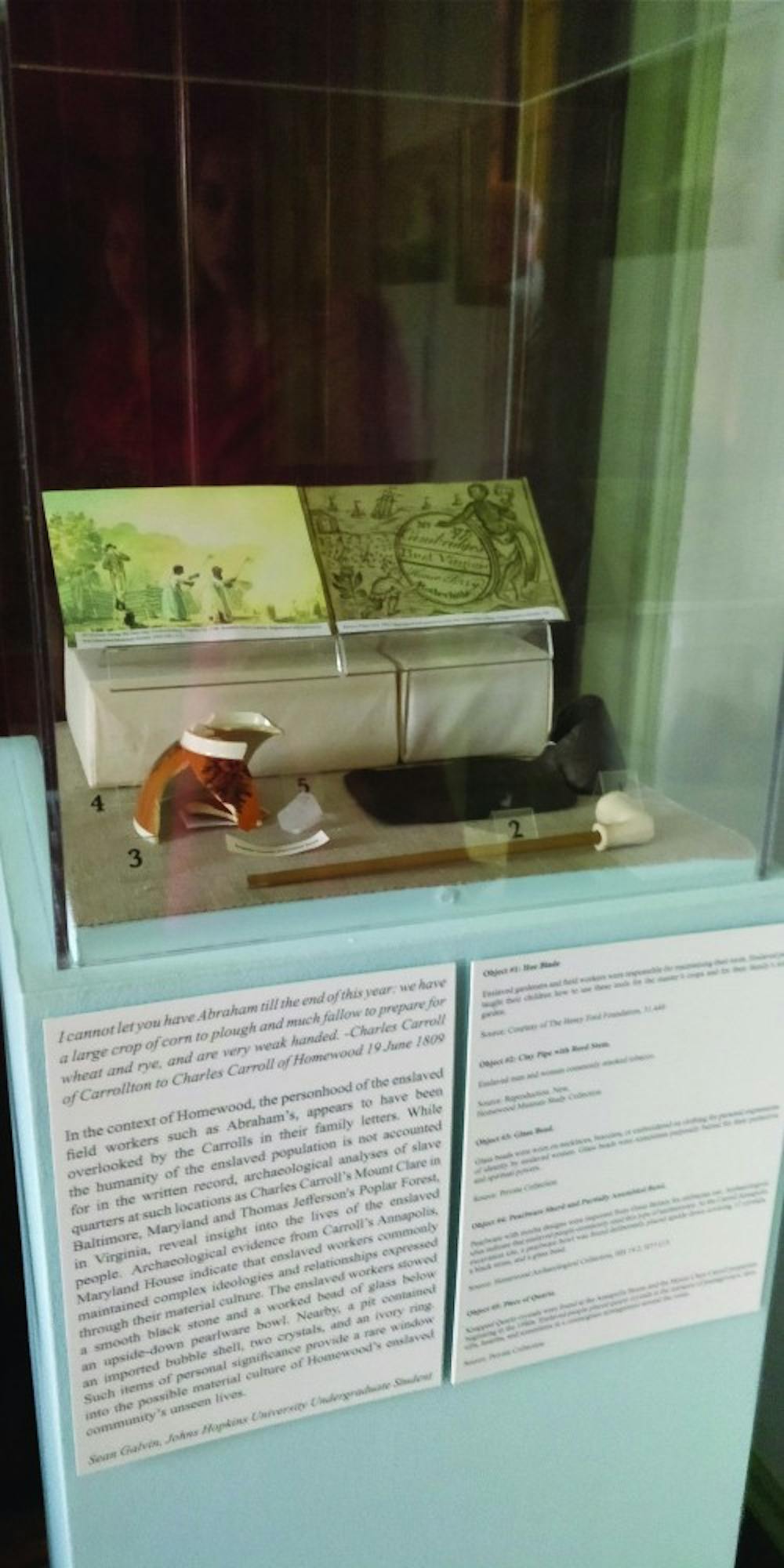

Senior Sean Galvin focused his exhibit on enslaved field workers at the Homewood estate. However, he had some challenges in his research because field workers were seldom referenced in historical documents.

“My exhibit is focusing on enslaved field workers at Homewood, and it’s pretty much archeology based, so we don’t have a lot of information about the field workers’ personhood beyond occasional mention of their names in letters,” he said.

The materials people leave behind, he said, could give useful insight into their ideologies and personal lives.

“My idea was to take some archeological artifacts from our collection and reproduce artifacts found in other Carroll sights, including the Annapolis house and Mount Clare in Baltimore,” he said.

Galvin said that student researchers at Hopkins have various tools at their disposal in order to explore the minute details of life for enslaved people.

He hoped to gain a greater sense of the personal lives of the enslaved through the materials that they left behind.

“All of us are thinking about new ways to learn about the enslaved population even though they’ve been erased from the letters and from the history,” he said.

Freshman Julianne Schmidt said that her exhibit was inspired by the artwork of African-American painter Kara Walker.

“My exhibit is about a contemporary visualization of race and gender,” she said.

Schmidt explained that she wanted to use a modern form of art to showcase the history of enslaved families at Homewood.

“I took the contemporary artwork of Kara Walker and paired it with the historic research of some of the enslaved individuals who lived at the Homewood House,” she said.

Walker is noted for using black cut paper silhouettes in her artwork that lack distinguishing features. The lack of distinguishing features in her artwork suggests that the people depicted are not individuals and do not have defined identities.

Schmidt used similar cut paper silhouettes in her exhibit and assigned the identities of enslaved people at Homewood to the silhouettes.

Freshman Yeji Kim’s project focused on education for the enslaved prior to the Civil War.

She chose to highlight this period because of the lack of information during this time compared to after the Civil War.

Her exhibit included an 1815 copy of a typical English dictionary found on site at Homewood.

“I thought it was quite cool and I really wanted to show the definition of education through this dictionary, what it meant then and how the meaning changed over time,” she said.

Her exhibit also contained artifacts that showed how education was gendered: girls and boys were exposed to different skills.

“For girls I tried to show it through the needles. Needlework was very prevalent,” she said. “For all females they’d be learning how to sew.”

Kim’s exhibit also included a mission statement from the Methodist Church that addressed the lack of schooling opportunities for enslaved persons.

“It’s a real turning point,” Kim said. “This was May 20, 1800 when this was issued and it is addressing that black students couldn’t get equal opportunity to education.”