Turmeric, known scientifically as Curcuma longa, does more than just add spice to the curry eaten all over the world. Native to southeast Asia, the orange and yellow plant has been used for centuries not just as a dye or a spice but also as a medical treatment. A lab in Germany has recently brought turmeric back into the medical playing field. The study, done by Maria Adele Rueger and her team, tested the compound’s utility in relation to diseases of the brain.

In India, turmeric use has been documented for at least 6,000 years as a medicine, a dye, a beauty aid, a spice and even a necklace to ward off evil. Chinese medicine uses it to treat the spleen, the stomach and the liver as well. The ancient Persian medical system used the herb to purify the blood.

As an herb known to contain antioxidants, antibiotics, anti-inflammatory action and preservatives, it is no wonder turmeric’s compounds have been under scientific consideration.

Curcumin and ar-tumerone are two of turmeric’s major chemicals with promising properties for disease treatment. More commonly studied, curcumin has anti-inflammatory properties that caused it to be considered as a treatment for diseases such as pancreatic and colon cancer, Alzheimer’s and arthritis. However, Rueger was interested in the possibilities of ar-tumerone.

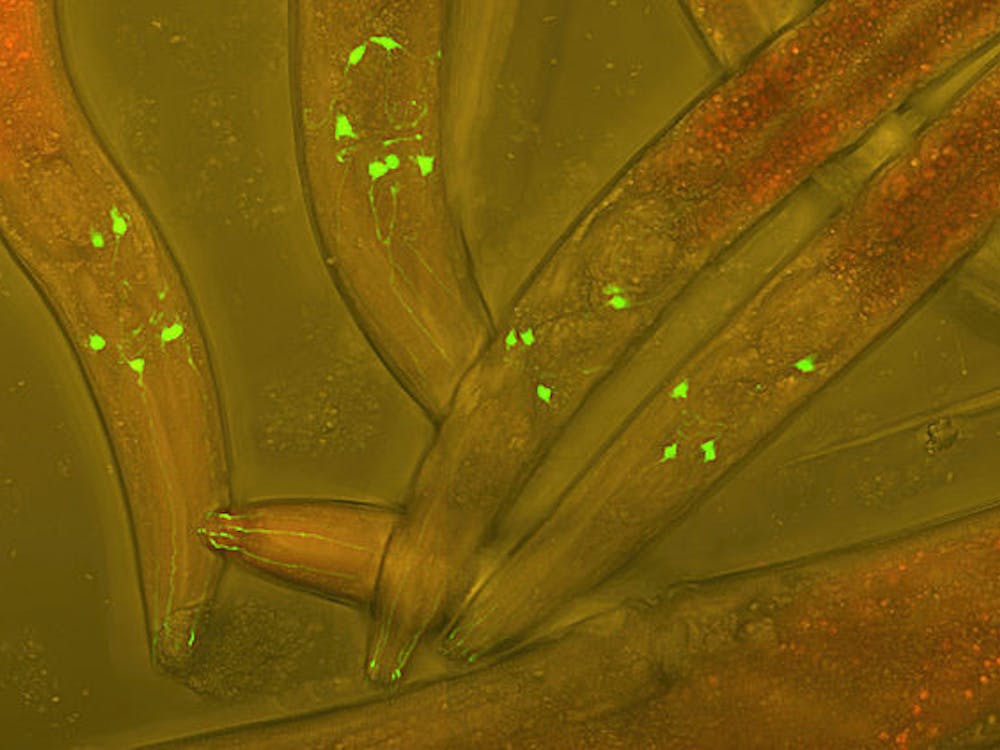

The researchers first looked at the compound’s effect on rat fetal neural stem cells. The cells were grown in vitro at different concentrations of ar-tumerone for 72 hours, and, amazingly, the neural stem cells were shown to increase by up to 80 percent with cell survival being unaffected.

The team also assayed the stem cells and found an increased differentiation of growing neurons, which means that the stem cells were developing into specific types of neural cells.

The in vitro effects encouraged the team to move forward into studying ar-tumeric´s properties in vivo. They saw an increase in the neuron cell populations around the subventricular zone of the rats’ brain, an area which is known to exhibit stem cell creation. The results on rat brains mimicked those seen in petri dishes, suggesting that the effects of the compound had the potential for which the team had been searching.

In previous studies, ar-tumerone has been known to exhibit differing effects when tested on different cell types. In some cell types, cells seemed to proliferate more, while in others proliferation ceased.

For example, some cancer cells divide less when exposed to ar-tumerone, while specific blood cells are known to divide more under similar conditions. However, the oncogenic, or cancer-causing, properties of cancer cells might be providing complications. This is especially true when controlling something as sensitive as cell division.

Because humans have such a complex brain and spinal cord, little is known about regeneration of damaged tissue. This makes neurodegenerative diseases, brain damage and spinal cord injuries hard to treat. With diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and multiple sclerosis affecting five million, one million and 400,000 people respectively, scientists are turning to neuroregeneration studies like this to improve the lives of millions.